Please join Valerie Stivers and Hank Zona for a virtual wine tasting on Friday, November 13, at 6 P.M. on The Paris Review’s Instagram account. For more details, visit our events page, or scroll to the bottom of the page.

On Halloween, when many people abandon themselves to the linked joys of sugar and horror, we more literary types decide to dine from transgressive fiction. I have at hand two books by the French writer Gabrielle Wittkop (1920–2002): Murder Most Serene and The Necrophiliac. The former, set in Venice between 1766 and 1797, is a murder mystery wherein the wives of a nobleman named Alvise Lanzi keep dying from poison. Perhaps the killer is his mother, Ottavia, whose basement cellar for Nebbiolo wine also hides “flasks and phials”; or it could be her cicisbeo who is also a spy; or the maid, Rosetta Lupi, in her “apron edged with lace”; or Alvise’s jilted lover Marcia Zolpan, a “fine-looking girl” with “a very short neck.” It could even be Alvise himself. The setting is one of grotesque, end-of-empire decadence. Elaborate feasts are the norm. The latter book, The Necrophiliac, is the diary of a man in Paris who, as the title suggests, has sex with the dead. It might be the most disgusting and challenging book in the alternative canon. We cannot understand Wittkop without it, but fortunately, in the parts I could bring myself to read, there wasn’t any food.

Wittkop is an elusive and legendary figure in European letters, but her work has been slow to appear in translation. Biographical information about her in English is scarce. She was born in Nantes, France, in 1920; she married a Nazi deserter named Justus in Paris during the occupation and later moved with him to Germany. In her afterword to Wittkop’s Exemplary Departures, the translator Annette David describes Justus as a “German essayist” and reveals that he was gay. Both Justus and Gabrielle died by suicide—separately, seventeen years apart—when faced with terminal illnesses. Gabrielle Wittkop wrote travelogues, arts coverage for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and novels that were popular in France and Germany. She was influenced by E.T.A. Hoffman, Edgar Allan Poe, Marcel Proust, Miguel de Cervantes, and Joris-Karl Huysmans, though her first and foremost love was the Marquis de Sade. She must have seen horrors in occupied and postwar Paris, but we can only speculate on how they influenced her worldview. Her preoccupation with death began, she said, in childhood. The narrator of Murder Most Serene offers this justification: “Why this obstinate dwelling over a corpse’s pluck? … Simply because it is there inside us all, day and night.”

I used squid as a substitute for cuttlefish, a popular local mollusk in Venice. Photo: Erica MacLean.

Transgressive writers tend to dwell on the connections between sex and death, beauty and decay, eroticism and horror. Wittkop is no exception. Her prose is stylized and exquisite no matter what she’s describing. A picnic lunch in Murder Most Serene begins, “Shelling her plate of slipper lobsters, Ottavia offers a wicked commentary in classical Greek on the filthy tales told her by an abbot, gorged like a sponge on the effluvia of the bathhouses.” Slipper lobsters (I googled them) are small, camel toe–looking crustaceans, now endangered but once a speciality of the Venetian lagoon. What is contained in “the effluvia of the bathhouse,” I can only imagine. The scene continues:

The party indulges in moleche, edible crabs that shed their shells when molting and are thrown alive into boiling oil. The party honors a Breganze Bianco with a fragrance of fresh hay and the color of buttercups … Mario Martinellei helps himself to more baby cuttlefish, and a Mezzetino cuts open the pate, which, disemboweled, spills forth its calf sweetbreads and kidneys in a thick vapor of entrails. Abandoning some chunk of half-nibbled carrion under a bush, green flies descend on the nectar. An Inferno of exceptional vintage, matured to the morbid sweetness of walnuts, accompanies buntings served with polenta, suckling lamb, and riso in cagnone. Reclining on one elbow, a Dottore declaims a sophism for public consumption, then whispers in the ear of a Colombina who lifts her mask to reveal the face of a very beautiful young man.

It’s a lot of fun.

Biscotti are referenced several times in Wittkop’s work. My favorite recipe uses vegetable oil and has a secret ingredient: self-rising flour. Photo: Erica MacLean.

The fun is maintained throughout the poisoning and death scenes. A woman on her descent toward eternity vomits “great lengths of silvery, acrid mucus.” An autopsy is performed. “Sawn open, the cranium is a casket like any other. The flesh is both flaccid and marmoreal, singularly compact and tight, like frozen fat.” A later wife goes out like this: “Each morning Rosetta administers a clyster to Teresa, who has always had a tendency to constipation. And though she suffers now from diarrhea the clysters are continued. On Sunday night, despite a high fever, she wishes to take her bath, and falls asleep in it. On Monday she is rather better, eats a lettuce soup and half a pigeon. That night she is gripped by a violent fever, vomits, and suffers alternate bouts of extreme cold and burning heat.” The careful description of symptoms runs on in this vein through the eighth day, when Teresa dies.

It’s baroque and wonderful, and I enjoy this vein of aestheticized gore—as many of us do, if we judge by our television programming—but I have never found transgression persuasive as theory. I comprehend the intellectual connection between sex and death, but on the daily, lived level where most of what matters takes place, the two experiences are pretty different—perhaps so different that they’re more meaningful when addressed as separate topics. Work like this also tends to claim that it will shock you out of your bourgeoise preconceptions or, as Murder Most Serene’s introduction says of Wittkop’s novels, “invite us to jettison our moral baggage.” That seems incoherent in literary criticism, as it would be undesirable in life.

The pigeon that appears in Teresa’s death scene is probably a squab (young pigeon), like this one. Photo: Erica MacLean.

And then I read The Necrophiliac (the parts of it I could bear) and decided that perhaps I’d just never read anything transgressive enough. In The Necrophiliac, Wittkop pushes the glee of horror and the choice of aesthetics over morality to the extreme. The protagonist’s descriptions of his many loves—“my boyfriends with anuses glacial as mint, my exquisite mistresses with gray marble bellies”—are so taboo that they actually made me giddy. Here is the comparatively mild beginning of one of his more acceptable relationships:

I celebrate the New Year in good company, that of a concierge from rue de Vaugirard, dead of an embolism. (I often learn this sort of detail during the course of a burial.) This little old woman is certainly no beauty, but she is extremely pleasant, light to carry, silent and supple, agreeable despite her eyes that have fallen back into her head like those of a doll. Her dentures have been removed, which causes her cheeks to sink in, but when I strip off her awful nylon blouse, she surprises me with the breasts of a young woman: firm, silky, absolutely intact—her New Year’s gift.

A translation of anything from this book into reality would, of course, be an atrocity. Nor could there be a made-for-TV version. As art, it’s defensible as freedom of expression, though I suspect its publishers would have trouble if anyone were paying attention. Moreover, “we can say it, so we should” is a thin justification. Yet I find the book intellectually and artistically fascinating, and I’m glad it exists. For me, the redeeming element of The Necrophiliac is that through extraordinarily skilled and beautiful writing, humor, daring, and glee, Wittkop seizes life from the jaws of death, pleasure from horror, and transforms her material into art. It couldn’t be done without her technical mastery, but she has done it, and it’s a kind of triumph.

Reading Murder Most Serene, I thought often of the human suffering Wittkop surely must have seen in Paris during and after World War II. How could anyone who lived through that possibly make light of death? It’s pure speculation, but after reading The Necrophiliac, I wonder if such work came about not despite but because of what she saw. Sometimes we appropriate horror to transform it, re-create things in our own words to make them safe, role-play trauma to rewrite it. Even Halloween has something of that spirit.

Lettuce soup is basically broth and lettuce blitzed with an immersion blender. Photo: Erica MacLean.

Thus inspired, I channeled the books’ sense of daring, thrills, decadence, and transgression when choosing my menu. I made the lettuce soup from the death scene in Murder Most Serene, mostly because “lettuce soup” sounded disgusting and I wanted to know if it could possibly be good. (No.) I researched all the items from the picnic scene above and discovered that cuttlefish are another lagoon speciality, buntings are ortolans, and riso in cagnone is a rice with cheese, similar to risotto. Cuttlefish were unavailable, so I opted for squid, a near cousin, and planned to clean it, remove the beak and bones, and stew it in its own ink. This was a challenge and thrill because I’m slightly squeamish when it comes to instructions like “make a firm cut directly beneath the eyeballs” and “sort through the innards to find the ink sac.”

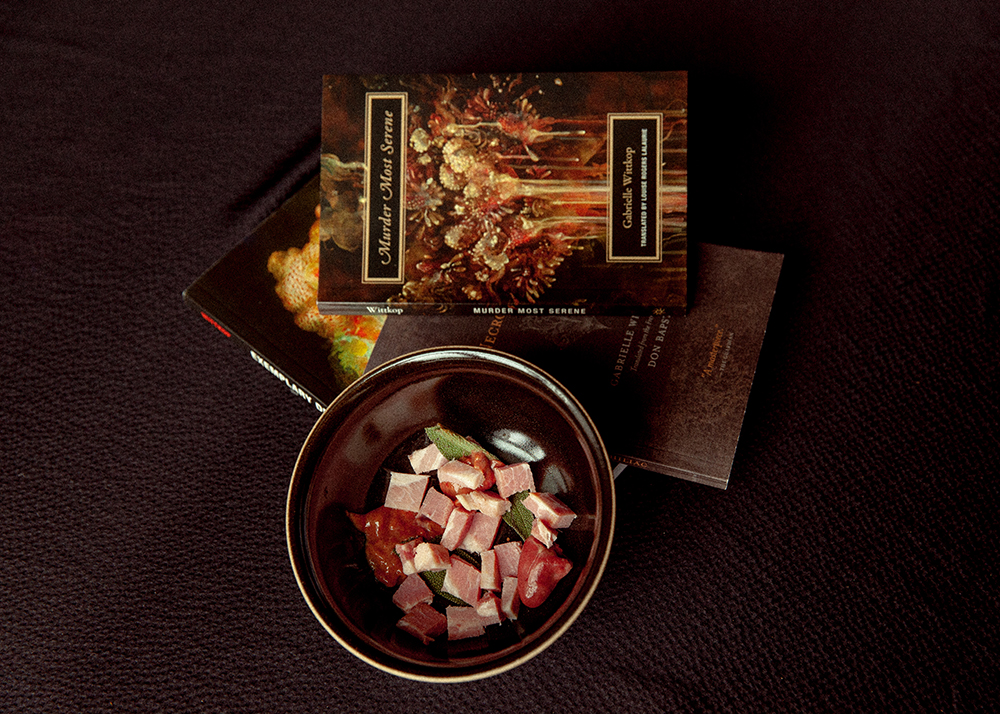

Ortolans are a protected species, so I substituted a different little bird to top my polenta—the pigeon from the death scene (squab, very pricey at twenty-five dollars a head from D’Artagnan). Following a Marcella Hazan recipe, I stuffed the squab with sage, pancetta, and its own heart and liver. Lastly, because there was a specific instruction to dip biscotti in the “warm, heavy amber of Tuscan Vino Santo,” I made biscotti with the Italian flavorings of almond and blood orange. Biscotti recipes vary widely; mine is from an Egyptian cookbook, and I consider it to make perfect, foolproof, not-too-sweet, crunchy cookies, something I’ve been waiting to share.

Wine makes many appearances in Wittkop’s prose, as when “women gorged with venom burst like wineskins.” Photo: Erica MacLean.

Wittkop was nearly as lavish with her descriptions of wine as she was with food and gore. Her references are period-authentic, too, according to my spirits collaborator, Hank Zona, and reflect the politics of the time. The “Inferno” wine mentioned in the picnic scene above comes from a subregion of the northernmost wine-producing region in Italy, Valtellina, which in the late eighteenth century was still a part of the Venetian Empire. It is called Inferno because the job of growing its grapes on nearly vertical terraced vineyards is hellish. Inferno, made from Nebbiolo grapes, was the precise wine suggested by Wittkop to go with my squab-and-polenta dish, and its acidic bite and aroma of roses provided a needed counterbalance to the bird’s rich, livery flesh.

Later in the same scene, Wittkop mentions that “everyone holds to the ruby red Valpantena.” That’s a wine from a subregion of the larger Italian wine-making region of Valpolicella, Zona explained. From a favorite biodynamic winemaker in Valpolicella, he suggested a light red that he thought would go well with my squid. This pairing was the surprise standout of the meal. The fresh squid was sweeter and more tender than any I’ve tasted, and the rich, unctuous black sauce, flavored with tomato paste and garlic, was magical with the acid and black-fruit flavor profile of the wine. Ideally, you eat this dish as a stew on day one, then toss the leftovers over pasta on day two.

Breaking down my own squid is something I’ll do again. There’s no comparison for freshness and flavor. Photo: Erica MacLean.

The squid success was all the more satisfying because I’d had some trepidation about cleaning it and getting the ink. In the end, the cleaning (and skinning and debeaking!) process was pretty easy, though I did have some misadventures with the ink sacs. The squid I bought in Chinatown during a trial run had sacs, but they seemed dried out by the time I tried to use them. The farmers market squid pictured in the photographs came whole and uncleaned, but both sacs were broken or empty. I ended up using canned cuttlefish ink as a backup, though I’ve read that it’s a faint imitation of the real thing. Overall, in fact, freshness is preferred with squid. The dish I loved on the day of the photo shoot made for some creepy, inky-black, tentacle-laden leftovers for the next day’s lunch. My slight revulsion felt appropriate to Wittkop, but the meal was even more unappealing after I warmed it up in the microwave.

Unlike her heroines, though, I’ll live and learn.

Lettuce Soup

Adapted from Leite’s Culinaria.

2 tbs butter

an onion, chopped

a medium potato, peeled and chopped

4 cups chicken or vegetable stock

salt and pepper (to taste)

a head of Bibb, Boston, or butter lettuce (5 cups)

1 cup fresh herbs (I used 3/4 parsley and 1/4 lovage)

fresh sunflowers or other cute shoots (for garnish)

Melt the butter. Add the onion, and sauté until glossy and translucent, around ten minutes. Stir in the potato, then cover and cook on medium-low for ten minutes, stirring from time to time so it doesn’t stick.

Add the stock, and season with salt and pepper. Bring to a boil, cover, and gently simmer until the potato is tender, about fifteen minutes. Add the lettuce and herbs to the pan, and cook until the lettuce has just wilted. Turn off the heat, and let cool slightly. Puree with an immersion blender.

Squid Cooked Like Venetian Cuttlefish over Pasta

Adapted from Tina’s Table.

2 lbs uncleaned, 1 lb cleaned squid

olive oil

three cloves garlic (ideally black garlic, if you can find it)

1/2 cup white onion, chopped

1 tsp squid or cuttlefish ink (just in case)

3/4 cup white wine

1/2 tsp chicken Better Than Bouillon

1 tbs tomato paste

salt and pepper (to taste)

1 lb spaghetti, cooked and drained

1/4 cup parsley, finely chopped

Clean and slice your squid following the method of your favorite online tutorial, reserving the ink sacs. (I especially enjoyed the man’s soothing voice on this one.)

In a medium saucepan, sauté the garlic and onion in a glug of olive oil for about three minutes until the onion is just translucent, then add the squid, and toss to combine. Add the squid ink (mash the sacs up with a spoon first if you’re using fresh ones; use about a teaspoon if you’ve opted for the canned variety). Toss to combine. Add the wine, bouillon, and tomato paste, and stir. Add more wine if you think you need more to cover the squid. Cover, turn the heat to medium-low, and cook at a simmer for twenty-five to forty minutes, checking regularly, until the squid is soft. Season to taste with salt and pepper. Toss with pasta and parsley to serve.

Pot-Roasted Squab with Polenta

Squab adapted from The Classic Italian Cookbook, by Marcella Hazan. Polenta adapted from How to Eat a Peach, by Diana Henry.

For the squab:

a squab

6 sage leaves

a strip of pancetta

salt and pepper (to taste)

1 tbs butter

1 tbs vegetable oil

1/2 cup white wine

For the polenta:

1/2 cup whole milk

1 cup water

1/2 tsp salt

scant 1/2 cup coarse cornmeal

2 tbs unsalted butter

3 tbs Parmesan cheese

To make the squab, remove all the organs from the inside of the bird. Reserve the liver and heart, but discard the gizzard. Wash the squab in cold running water, and pat dry thoroughly inside and out. Stuff the cavity of the bird with two sage leaves, a strip of pancetta, the heart, and the liver. Season the outside of the bird liberally on all sides with salt and pepper.

In a pot just large enough to hold the squab, heat the butter and oil over medium-high heat. When the butter foam subsides, add the remaining sage leaves and then the squab. Brown the squab evenly on all sides. Add the wine. Turn the heat up to high, allowing the wine to boil briskly for thirty to forty seconds. While the wine is bubbling, turn and baste the squab, then lower the heat to medium-low and cover the pot. Turn the bird every fifteen minutes. It should be tender and done in an hour.

Transfer the squab to a warm dish. If you’re serving half a bird per person, halve it with a knife or poultry shears. Tip the pan and draw off most of the cooking fat with a spoon. Add two tablespoons of warm water, turn the heat to high, and scrape up any loose cooking residue in the pan while the water evaporates. To serve, place the squab on a bed of polenta, and drizzle with the sauce.

To make the polenta, put the milk in a large, heavy-based pan with the water and half a teaspoon of sea-salt flakes. Bring to a boil. Add the polenta, letting it run in thin streams through your fingers, whisking continuously. Stir for two minutes until it thickens.

Reduce the heat to your lowest setting and cook, mostly covered, for forty minutes, stirring every four to five minutes to prevent the polenta from sticking. When it’s done, it should be coming away from the sides of the pan. You might need to add more water; it shouldn’t get dry and stiff but should be thick and unctuous. Stir in the butter and Parmesan, tasting for seasoning.

Blood Orange Biscotti with Almonds

Adapted from The Taste of Egypt, by Dyna Eldaief.

3 eggs

1/4 tsp vanilla

1/2 cup sugar

1 tsp blood orange zest

3/8 cup vegetable oil, plus extra for greasing

1 1/2 cup flour

1 1/2 cup self-rising flour

1/4 tsp baking powder

1/2 tsp cinnamon

1/4 cup milk

1/2 cup candied blood orange peel, chopped

1 cup slivered almonds, toasted

Preheat the oven to 325. Place the eggs and vanilla in a large bowl, and beat together. Add the sugar, blood orange zest, and oil, and beat until well combined. Sift the flours, cinnamon, and baking powder together. Add the milk to the egg mixture, then add the flour slowly, stirring until still lumpy and just combined. Use only as much flour as required to make the dough just come together.

Lightly grease a baking tray with oil, and use a spoon to place two rectangular logs of dough, about three inches wide and an inch high, on the tray. Transfer to the oven, and bake for fifteen to twenty minutes, then remove. Cut the half-baked cookies into half-inch slices and place them on a baking tray lying on their sides. Reduce the oven temperature to 300, and bake for a further fifteen minutes. Turn off the oven, but leave the cookies in the oven to dry.

Wine!

Please join Valerie Stivers and Hank Zona on Friday, November 13, at 6 P.M. for a virtual literary wine tasting on The Paris Review’s Instagram account. We will be discussing the many wines mentioned in Wittkop’s work and how to pair them with food.

The wines seen in the story are Musella Valpolicella Superiore 2017, Nino Negri Inferno Valtellina Superiore 2017, and Felsina Vin Santo del Chianti Classico 2008. We encourage participants to source their own bottle and taste with us. Valpolicellas should be available in any good wine store; the designation “superiore” represents a higher quality. Particular bottles from the Musella biodynamic winery are available at some stores in Brooklyn and Manhattan. To find a bottle similar to the Nino Negri Inferno, ask for a Nebbiolo from Lombardy or Piedmont, which should also be widely available. But first check if the store has an Inferno—it might. Vin Santo is a dessert wine and is more expensive at thirty to fifty dollars a bottle, but it’s carried in all quality stores. Felsina is an excellent maker of Vin Santo at a mid-range price.

Anyone who would like more specific advice on how to find these wines near them can email us (hank@thegrapesunwrapped.com).

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2TAkJg2

Comments

Post a Comment