The History of EC Comics tells the story of one of the most infamous and influential forces in twentieth-century American pop culture. Founded in 1944, EC Comics quickly rose to prominence by serving up sharp, colorful, irresistible stories that filled an entire bingo card of genres, including romance, suspense, westerns, pirate tales, science fiction, adventure, and more. Perhaps most crucial to the company’s success, however, was its pivot to horror. In the following excerpt, Grant Geissman chronicles the origins of such gruesome, bone-chilling series as Tales from the Crypt and explores how the relationship between two key figures—the artist, writer, and editor Al Feldstein and the company’s publisher, Bill Gaines—acted as an engine that propelled EC Comics to the forefront of the industry.

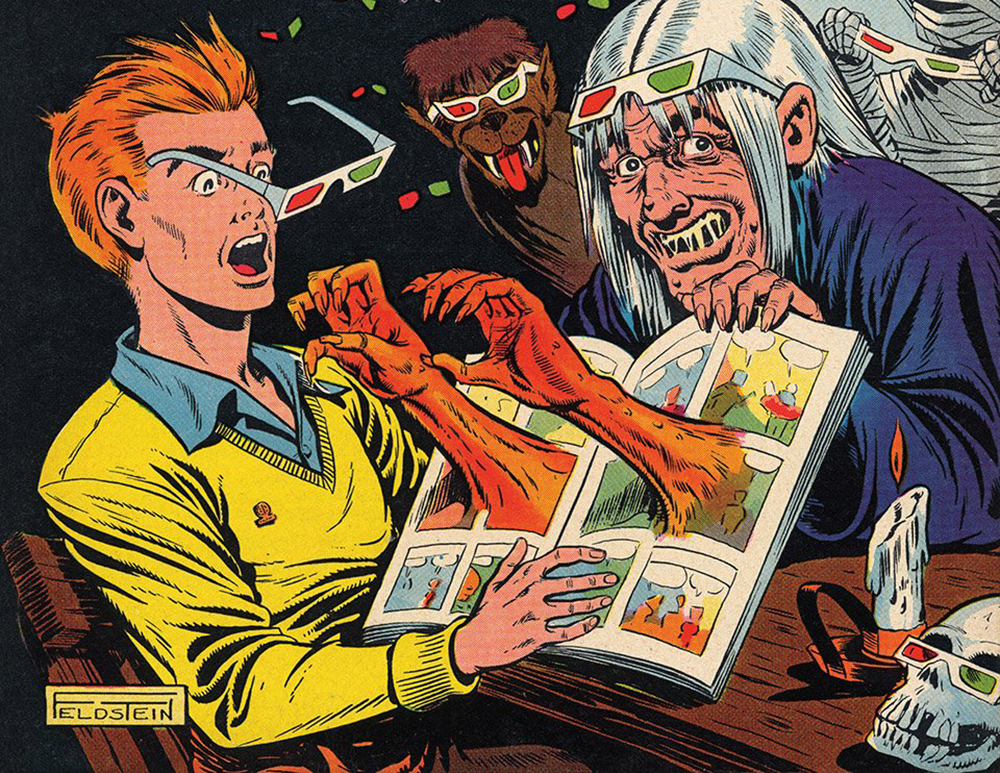

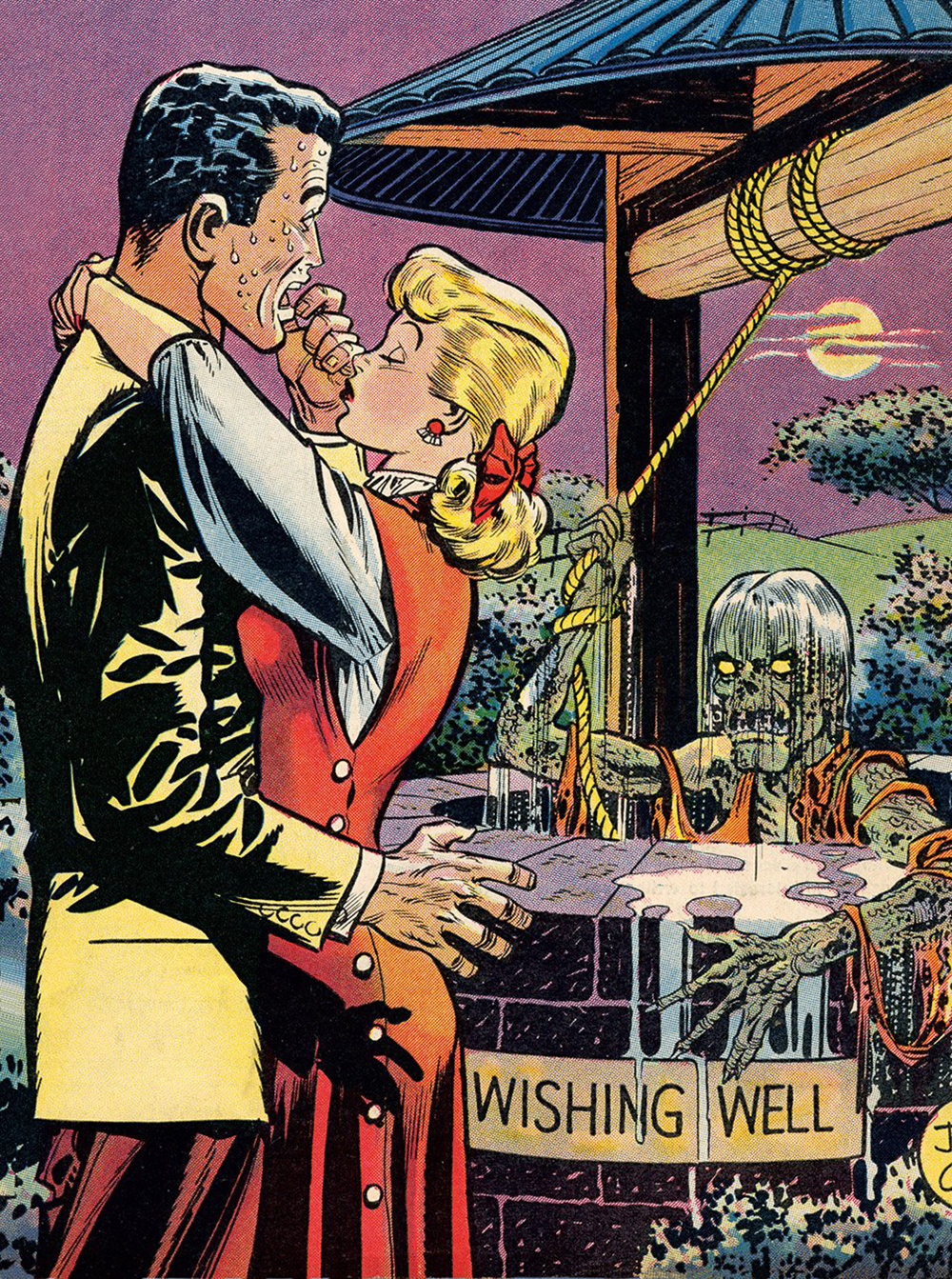

Detail from the cover of Three Dimensional Tales from the Crypt of Terror No. 2, Spring 1954. Art by Al Feldstein. Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

With Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein both working and hanging out together, Feldstein had the boss’s ear. On their car rides to and from the office, Feldstein began to chide Gaines for playing follow-the-leader. “You’re taking Saddle Justice and turning it into Saddle Romances because Simon and Kirby came out with a romance book and it’s doing well,” the ever-ambitious Feldstein said to Gaines. “We’re gonna follow them and get clobbered when it collapses, just like the teenage books collapsed. Why don’t we make them follow us? Let’s start our own trend.”

Gaines and Feldstein had talked about the old radio dramas they had loved as kids, shows like Inner Sanctum, The Witch’s Tale, and Arch Oboler’s Lights Out. Inner Sanctum and The Witch’s Tale both featured hosts who introduced the tales—the former by “Raymond,” a spookily sardonic punster, and the latter by “Old Nancy,” a cackling witch. Feldstein recalled that as a kid he used to climb down the stairs to sneak a listen, and was happily terrified by them. Gaines had similar recollections. Feldstein kept pushing for that, and Gaines finally said, “Okay, we’ll try it.” This was, in fact, a somewhat similar concept to the one the artist Shelly Moldoff had pitched on the aborted Tales of the Supernatural comic. Gaines was apparently mum about the situation with Moldoff, and Feldstein later said that he knew nothing about it at the time.

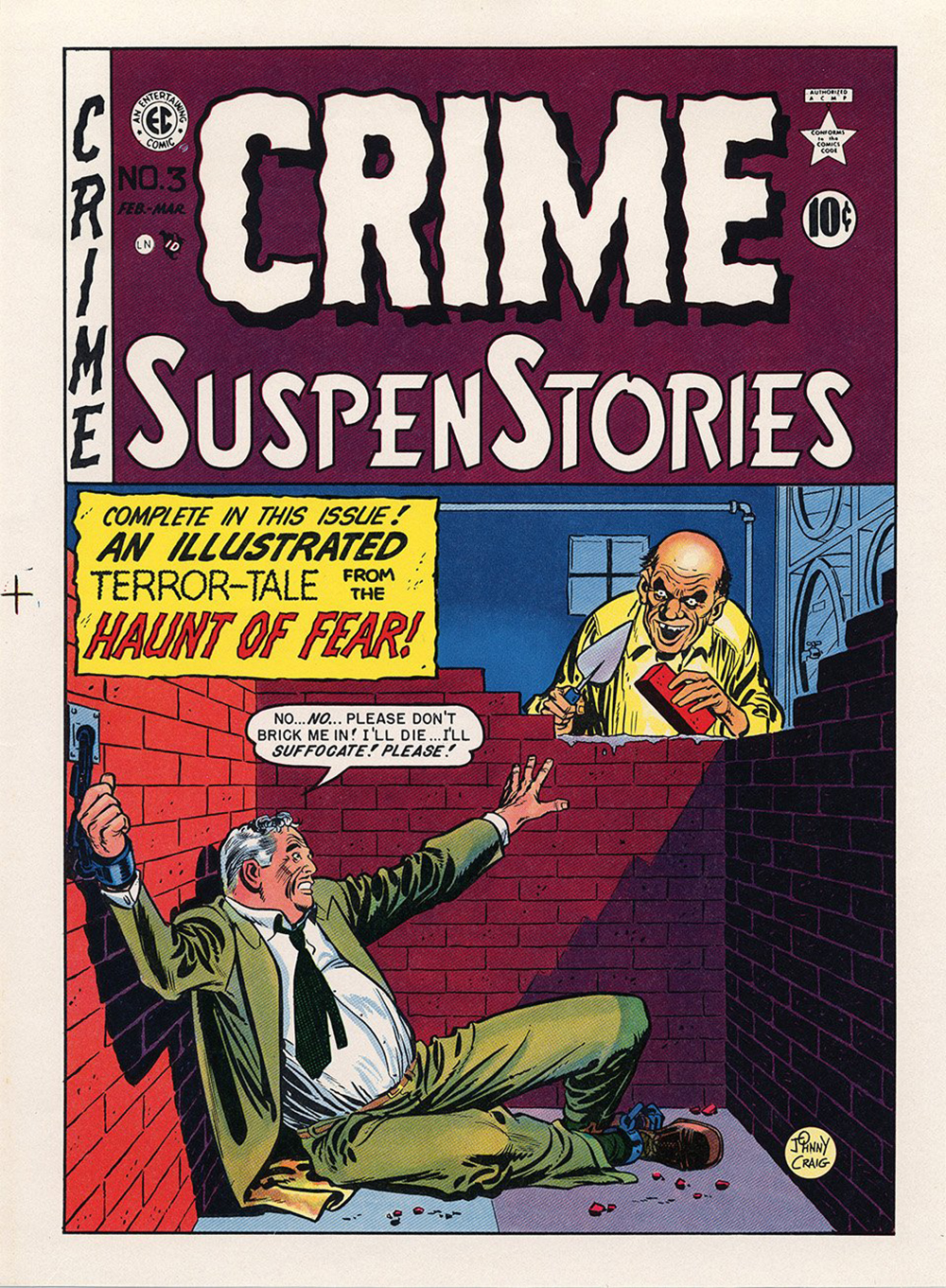

An untrimmed press proof of Johnny Craig’s cover to Crime SuspenStories No. 3 (February–March 1951). Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

So with the December 1949–January 1950 issues of Crime Patrol (no. 15) and War against Crime! (no. 10), EC introduced what was billed on the covers as “an Illustrated Terror-Tale from the Crypt of Terror!” and “an Illustrated Terror-Tale from the Vault of Horror!” Feldstein wrote and illustrated both stories.

The story from the Crypt of Terror was hosted by The Crypt-Keeper, and the story from the Vault of Horror was hosted by The Vault-Keeper, both inspired by the hosts from the old radio shows. Hedging the bet, “The Crypt of Terror” appeared in the last position in Crime Patrol. (However, “The Vault of Horror” story occupied the first slot in War against Crime!) The covers of both comic books were done by Johnny Craig, who had done all of the previous covers for both titles.

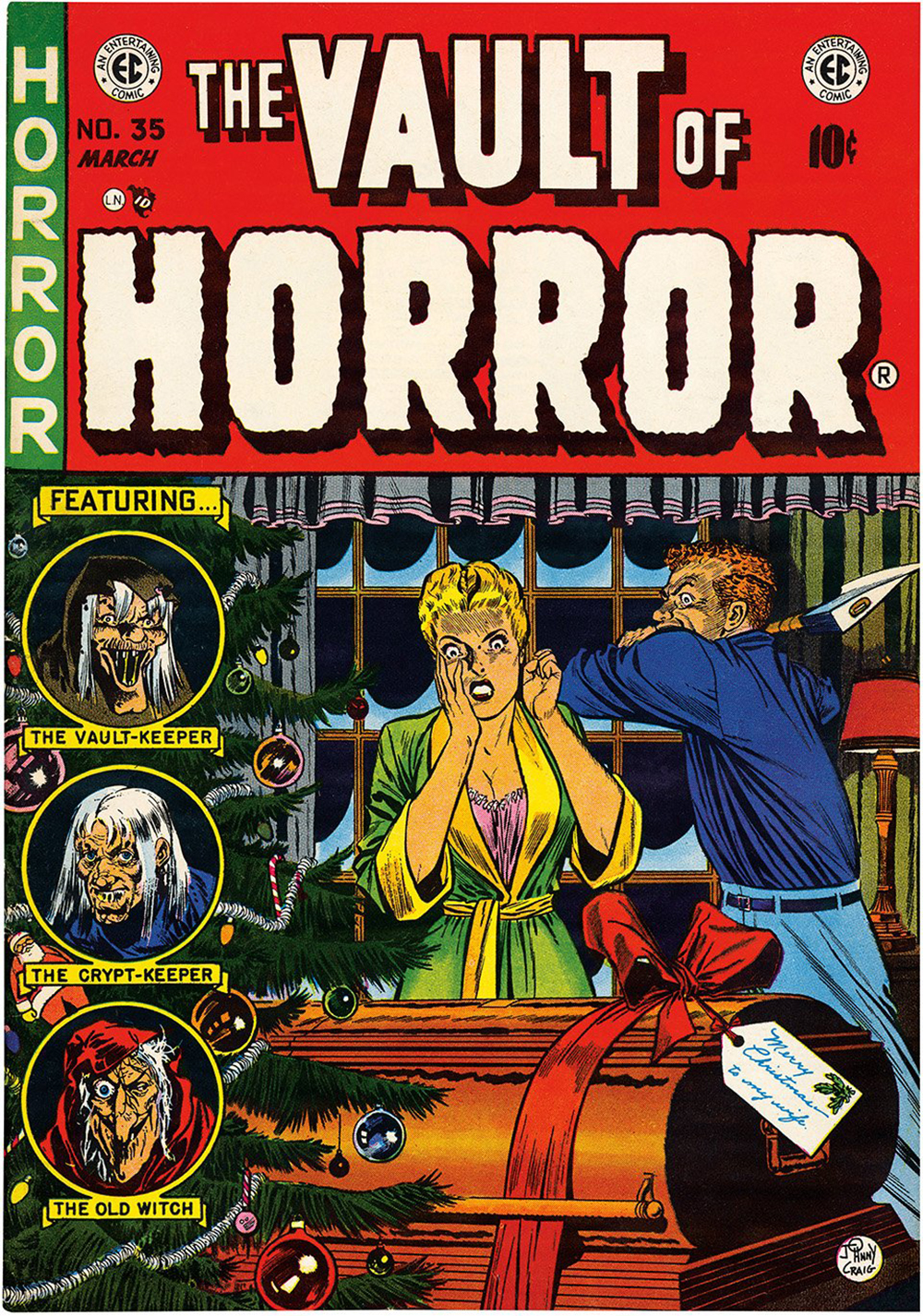

Johnny Craig’s Christmas cover of The Vault of Horror No. 35, February– March 1954. Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

Gaines liked the experiment well enough, because the next issues of both books (Crime Patrol no. 16 and War against Crime! no. 11, both February–March 1950) contained further installments, with the stories in the same positions as before. Craig again contributed the cover art for both books.

Gaines and Feldstein liked doing these stories, and it did seem like they were onto something. Back then the wholesalers employed “road men,” guys who checked the newsstands to see how things were selling. When they sent back the “ten-day check-ups” indicating strong sales for the experimental issues of Crime Patrol and War against Crime!, Gaines and Feldstein went all in for horror. And a New Trend was ushered in at EC.

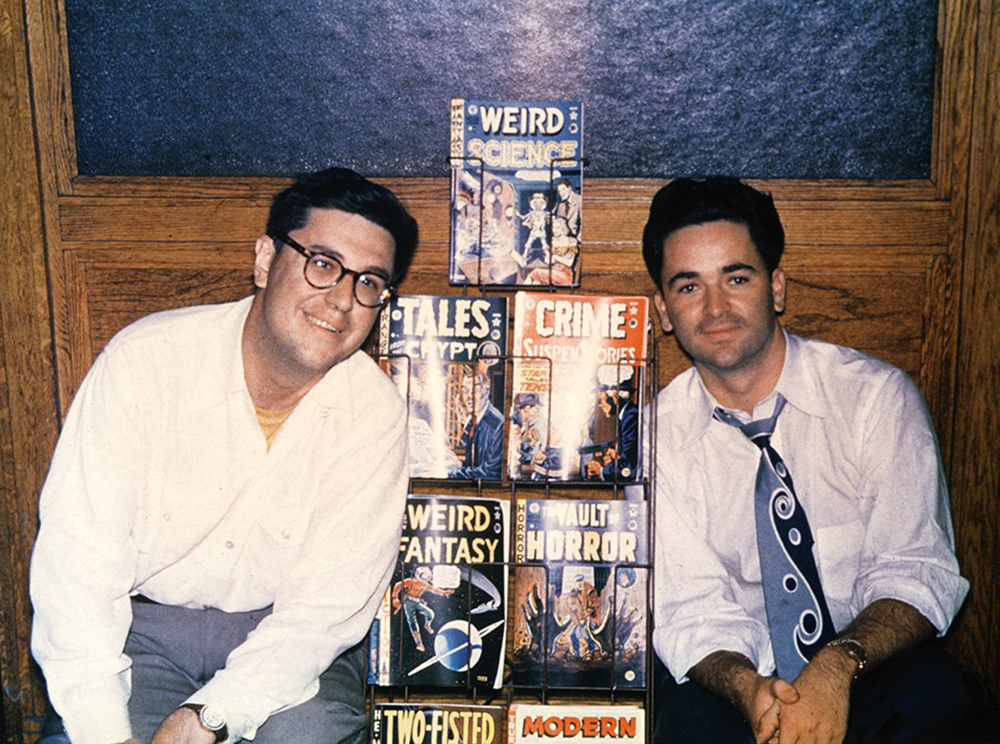

Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein in the EC office in late 1950, with a rack of their latest comic books. Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

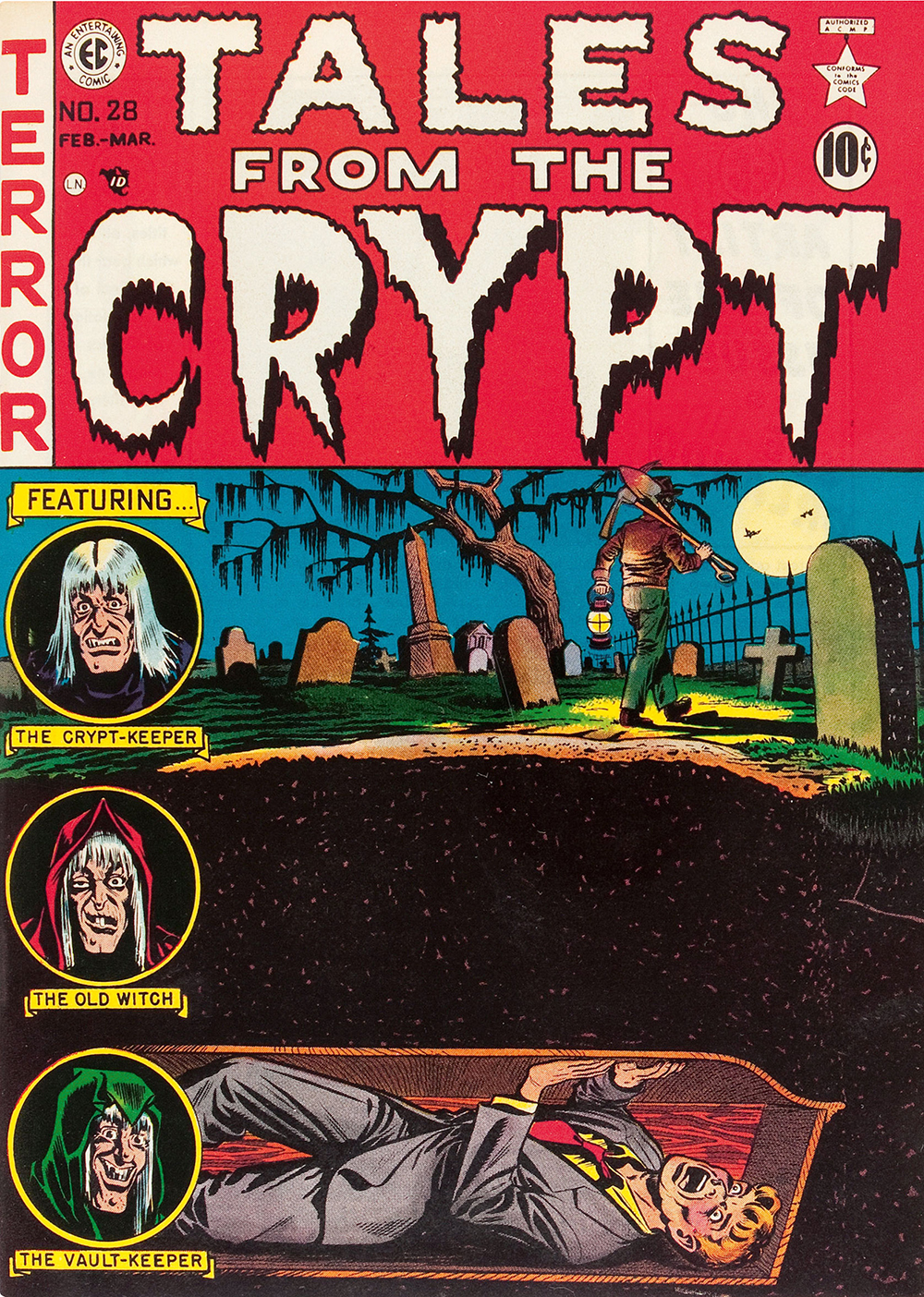

With the seventeenth issue they changed Crime Patrol to The Crypt of Terror, and with the twelfth issue they changed War against Crime! to The Vault of Horror. Both comics were April–May 1950. A month later they changed Gunfighter to The Haunt of Fear. (They changed the title of The Crypt of Terror to Tales from the Crypt three issues later, after “the wholesalers made some noise,” according to Gaines.) All three books continued the numbering from the previous titles, Gaines’s usual ploy to avoid paying the fee for a second-class mailing permit on a new title. (He got away with this on the first two titles, but on The Haunt of Fear they had to change the numbering, starting with the fourth issue, and pay for a new permit.)

With the second issue of The Haunt of Fear (no. 16, July–August 1950), Gaines and Feldstein also added a third horror host, The Old Witch, and the unholy trio of hosts was complete. The Three GhouLunatics—as the three horror hosts came to be called—would appear at the beginning and end of each story and offer up punny, smart-alecky commentary. EC’s new horror comics were pretty much an instant hit with readers, and Gaines, Feldstein, and Craig all shared that enthusiasm. EC’s business manager, Frank D. Lee, was not as enthused. When asked how he liked a new cover or story, Lee responded, “I don’t like it.” Feldstein said that Lee was “pretty grumpy” about EC’s new comics and openly expressed his dislike for them. Lee wasn’t the only naysayer. Sol Cohen, who had been advising Gaines, declared “the ship is sinking,” and bailed sometime in 1949 for a position as a comic book editor at Avon.

Detail from the cover to The Vault of Horror No. 18, April–May 1951. Art by Johnny Craig. Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

Johnny Craig illustrated the covers for the first several issues of all three of the horror titles, and also illustrated the cover of every subsequent issue of The Vault of Horror. A fine—but very slow—craftsman, Craig told Roger Hill: “I was supposed to do three stories a month. I was lucky if I did one.”

Playing with the “A New Trend” blurbs on the covers of EC’s new comics, collectors began to refer to the comics published before that as “Pre-Trend” comics, and the term stuck. Not all that many Pre-Trend artists managed to jump into the New Trend. Graham Ingels continued to work on the company’s “love books,” but he soon turned out to be the quintessential horror artist. Bill Gaines said: “In the early days of EC we had Graham typecast into the western books, and when we started the love books we used him there for a few stories, but he didn’t seem to fit. When we started the horror titles, we didn’t use Graham because we thought he’d be good at it, we used him because whenever an artist came into the fold we had to use him for something. So we stuck him in the horror books, and it didn’t take us very long to realize what had happened—that Graham Ingels was ‘Mr. Horror’ himself.” Gaines and Feldstein started calling him “Ghastly Graham Ingels” in the letter columns in 1950, and the name stuck. Ingels started signing his work with the pen name “Ghastly,” and began specializing in what Bill Gaines’s biographer, Frank Jacobs, once famously referred to as “cadaverous inkings.” Ingels’s horror tableaux are fetid, swampy, decaying, and oozing, and when depicting a rotting, shambling corpse, he was second to none. As the horror comics developed, Ingels also became known for his interpretation of the grinning visage of The Old Witch.

Feldstein wrote (and drew) all of his earliest EC horror stories on his own, and the rest of the stories in the early horror comics came from outside scriptwriters like Gardner Fox and Ivan Klapper. Within a very short time Gaines started bringing in snippets of ideas to be fleshed out into complete stories. At the time, the perpetually chubby Gaines was taking a prescription appetite suppressant that contained Dexedrine, which affected his sleep. Gaines would stay up half the night reading pulps and collections of horror and science-fiction stories. He scribbled plot ideas on scraps of paper he called springboards, and brought them to Feldstein the next morning. (Gaines also worked with Johnny Craig on stories in a similar fashion.)

It was a frantic schedule. Four days a week, Gaines and Feldstein hammered out plot ideas from Gaines’s springboards, with Feldstein always mindful of which artist they were plotting the story for that day. If Feldstein didn’t think a particular plot could be made into a script that would fit a particular artist’s style, he would pass on it, and Gaines would have to pitch another idea. Gaines said: “Al and I would sit down, and I would have to sell Al on one of my springboards. That’s what it amounted to. After he had rejected the first thirty-three on general principles, he might show a little interest in number thirty-four. I’d then give him the hard sell and he’d get going. He’d run into the next room and start working out the plot.” Although many of these springboards were inspired by existing stories, the duo invariably changed and improved upon the plots, in some cases making a far better yarn than was told in the original source.

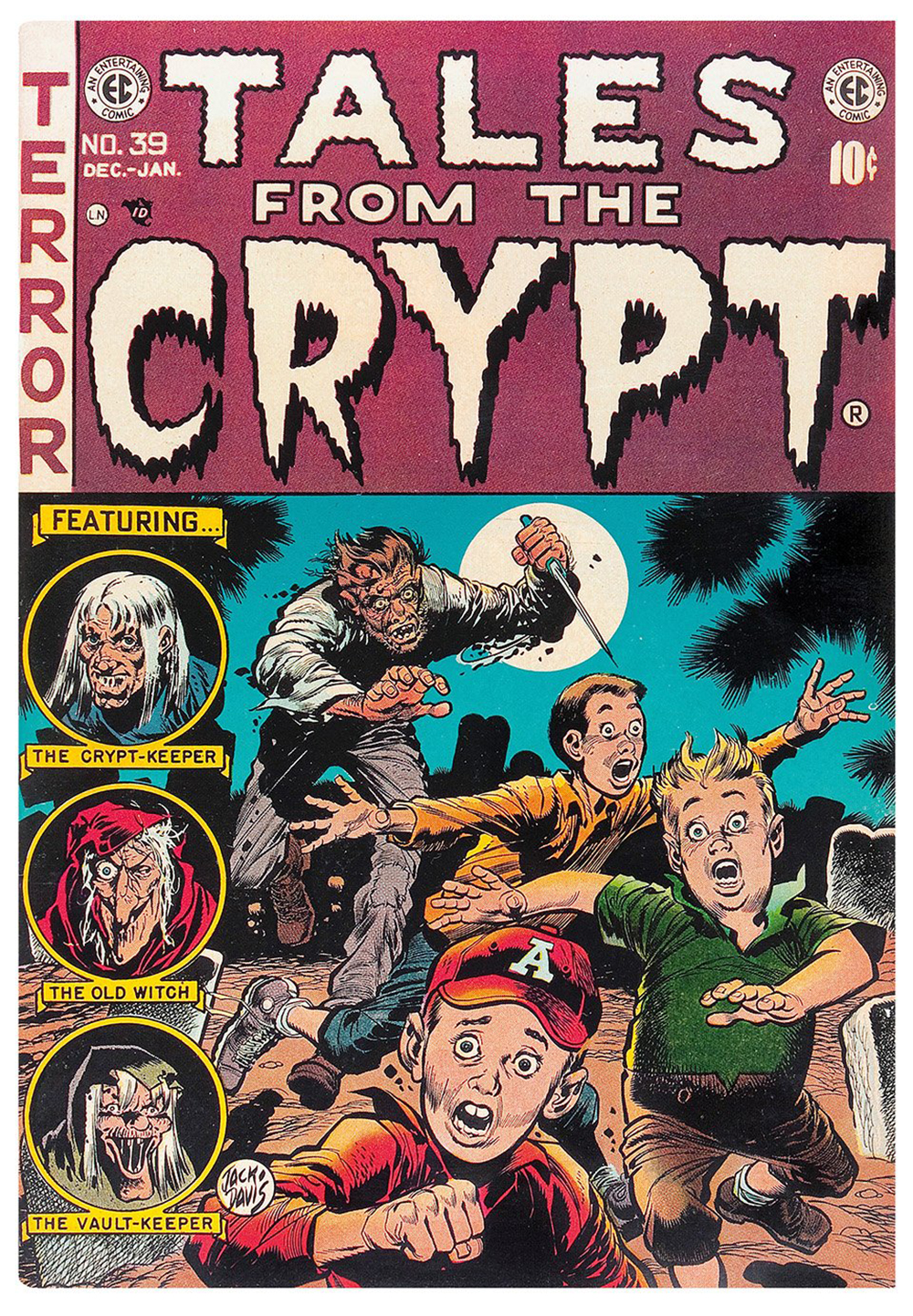

The cover of Tales from the Crypt No. 39. December 1953–January 1954. Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

Once they had set a plot, the two might work on some “fill,” fleshing out the plot a bit further. By then, it would usually be lunch time, and Gaines and Feldstein (and often Craig, along with any artists who might be in the office picking up or dropping off a job) would go to lunch at a nearby Italian place called Patrissy’s, where, Feldstein recalled, “we all got fat. They had great Italian food.” After lunch, Gaines would do paperwork and so forth, and Feldstein would write the actual story. (There was never a typed script; Feldstein would write the stories directly onto the art boards.) Gaines often had a nervous stomach at this point, because “I never knew if and when Al would come bursting back in and say ‘I can’t write that Goddamn plot!’ ” Then the pair would have to start the process all over again, because, said Gaines, “we must have a story by five o’clock.”

The horror stories Feldstein and Gaines came up with were all designed to have twisty, O. Henry–type endings, with the protagonist virtually always exacting a well-deserved measure of poetic justice against the antagonist, even if the protagonist had to somehow return as one of the walking dead to exact his revenge. This was Old Testament, an-eye-for-an-eye–style retribution, with the irony being that Gaines was an atheist. The EC horror stories were gory and many went way over the top, but this was fantasy, remember. Gaines said: “The old EC stories were largely sick humor. Almost every one of those horror stories was tongue-in-cheek. That stuff was strictly fantasy, and in the field of fantasy I’ll go as sick as you want. But if I see real blood, I’ll faint.”

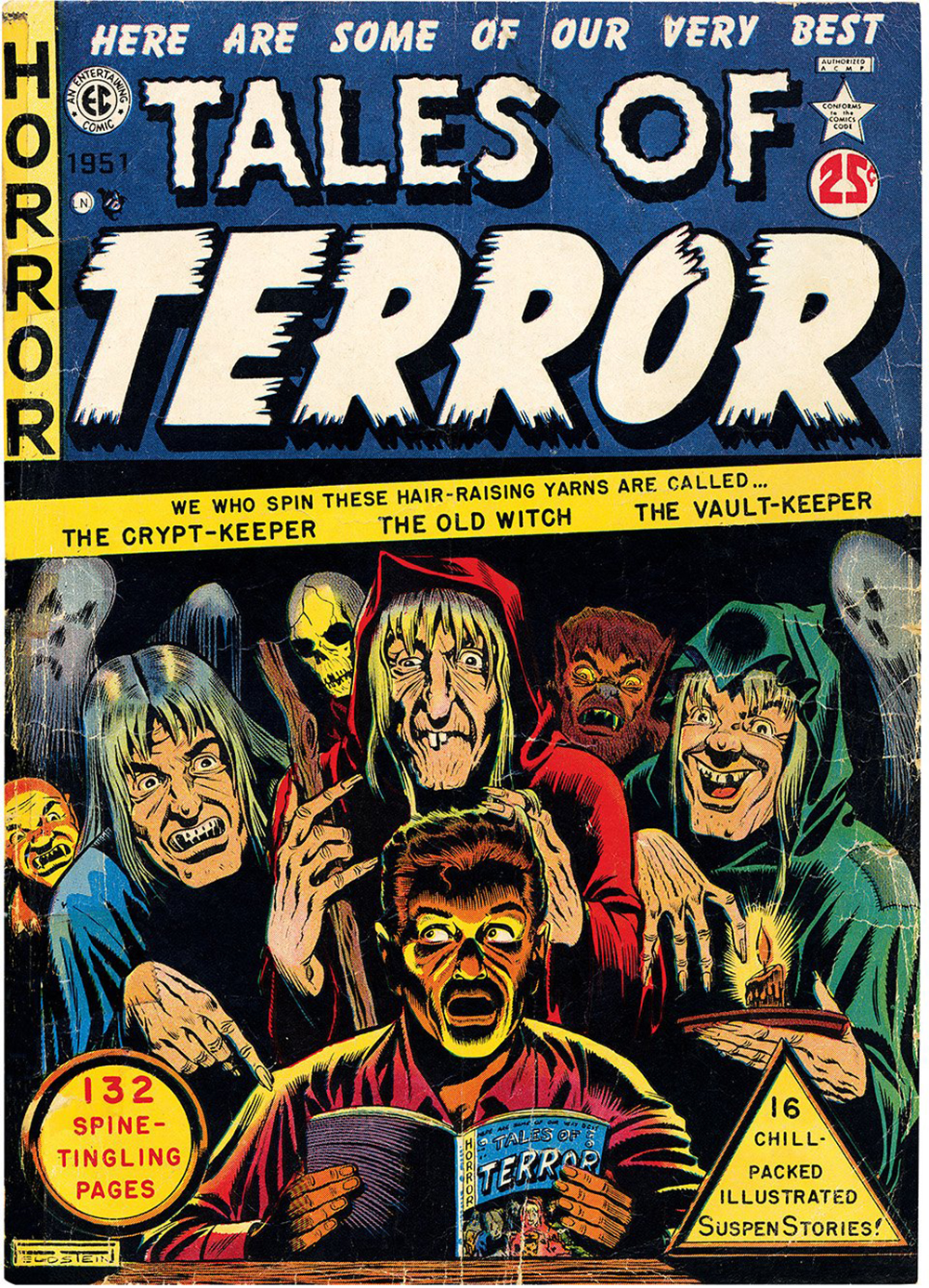

The cover of one of the three issues of the Tales of Terror annuals, issued in 1951. Cover art by Al Feldstein. Copyright: TM & © William M. Gaines Agent, Inc.

Grant Geissman is one of the world’s leading experts on EC Comics and Mad magazine, and the author and designer of four books on the subject. He is also an Emmy-nominated guitarist and composer who cowrote the music for the hit television series Two and a Half Men and Mike & Molly.

Excerpted from The History of EC Comics. Text copyright © 2020 by Grant Geissman. Published by TASCHEN.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3oDQ2F1

Comments

Post a Comment