On Amazon, there’s a used copy of the triple disc set from 1985 for sale, the first version issued on CD, in one of those chubby old double jewel boxes. Supposedly, there’s a Verve Master Edition version from the 1990s that added a forth disc, I guess of alternate takes or rarities, but I can’t find that anywhere. On eBay, I could get the original vinyl box set from the 50s or 60s, but it’s really expensive. Plus I have the first LP already. I could try to track down the other LPs one at a time. But what I really want is that forth CD on the Master Edition version …

This is how my nights unfold as the days get shorter and darker in these uncertain times—after the dog’s last walk, after heaving my son into bed with the Hoyer lift and attaching his CPAP, after the third time my daughter comes out of her nightlighted room to share another phrase she’s come up with that contains all the vowels, but before my smoking time on the back deck, before the anxious and rambling conversation with my wife in my little book-and-record-crammed office, and certainly before the Hour of Enforced Unplugging, when I finally roll into bed—I scour the web for out-of-print CDs and vinyl. They’re artifacts from a lost time when I was young and not so poignantly terrified or from an even more distant past I never experienced, a past that was gone long before I arrived. It’s easy to imagine that those times were simpler, better, easier than the interminable weeks of COVID-19 in Trump’s wrecked America.

Of course, last night interrupted this pattern—I gave in, like any sane person under the thumb of this insanity, and spent the hours on the opposite end of a couch from my wife, the two of us refreshing counters, screaming at virtual needles, in the thrall of our fear and hope for this election. And today, as we’d dreaded and expected, we wait, and I call on one of my time-tested coping mechanisms for, if not solace or even distraction, a kind of anxious business that might help pass the hours between now and the end of forever.

Over the last eight months, my CD and vinyl shopping has gotten seriously out of control. I am, like Theodore Roethke in his poem “In A Dark Time,” longing for a “steady stream of correspondences.” I need at least a package a day to remind me the world’s still out there, that there are things to look forward to. It’s a call for help that online merchants—not just Amazon, but indie records stores trying to survive and strangers selling off their late fathers’ record collections on eBay—are happy to answer.

Streaming threatened to destroy my favorite pastime, the obsessive quest for music—if everything is available, what is there to collect?—until I realized I could simply ignore it and pretend that I only have an album if I have it on a physical medium. Old CDs and records are cheap now; no one seems to want them but me. So I troll the web, leaping as ever from one lily pad to the next, from liner notes to Wikipedia pages to Buy Now buttons, artists leading me to their friends and collaborators and competitors, whose names I dig out of liner notes and nerdy online info hubs.

I am precisely, and sort of ashamedly, the cliche of the record collector, hoarding my things, T.S. Eliot-like: “These fragments I have shored up against my ruins.” It’s the collector’s time-honored fallacy: that the talismans of this arcane knowledge are weights that keep the days and the hours from floating off into the ether.

At the moment, I’m searching for a playable copy of Ella Fitzgerald’s complete George and Ira Gershwin songbook album, the crown jewel of her songbook series for Verve, recorded from the end of the 50s through the mid-sixties. These are Ella’s most enduring and beloved recordings, on which, at the behest of her manager, producer, and label owner George Granz, she devoted an album a piece to the major composers of the Great American Songbook—the Broadway anthems and radio hits of the early-middle 20th Century that became jazz standards, the soundtrack to all our great aunts’ younger days. The Gershwin set, with Ella lavishly backed by Nelson Riddle’s orchestra (see how the useless facts pile up, pinning the wind blown sheet of my life in place), is 53 songs on several CDs or LPs or an unparsable streaming playlist. It is an undeniable masterpiece, Ella’s voice at its peak, weaving in and out of these timeless melodies, which swell and contract as the orchestra carries her like a wave pulled back toward the depths. It’s heaven, it’s soothing, and yet all the world’s heartbreak seems to echo through these songs.

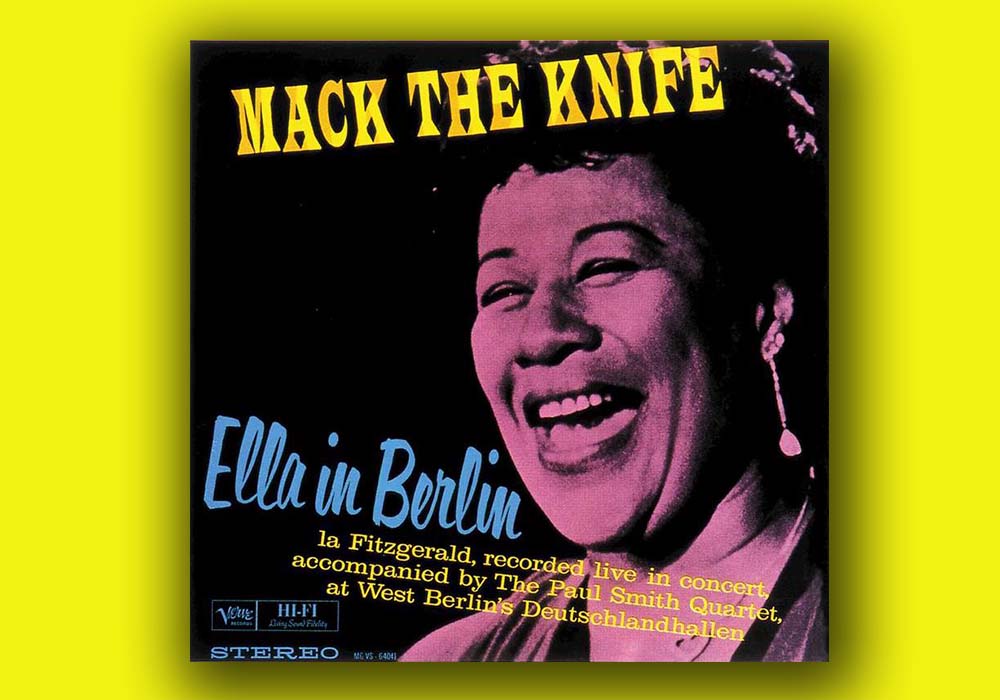

I first discovered Ella Fitzgerald as a teenager, reeling from the death of my mother when I was 14. I plunged, as a high school junior, into a mighty depression, one of the effects of which was that I could no longer enjoy music with words—all of that emotion seemed painfully ironic to my little heart, which, for a while, couldn’t feel anything (not unlike today). So I began to explore jazz, music which qualifies as what William Carlos Williams calls, in “The Orchestra,” “sound addressed/ not wholly to the ear.” It was music I could think about, could approach without immediately springing my raw nerves. I started with the classics—Louis Armstrong and Miles Davis, and, soon enough, Ella—these words I could handle, if only because I could hear the roiling history beneath them. When I first heard Ella’s infamous live rendition of “Mack the Knife” from 1960, on which she improvises her own lyrics about the very song she’s singing because she forgot the real ones, a little pinprick of light opened (and still opens) in my darkness:

Oh Bobby Darin and Louis Armstrong

They made a record, oh but they did

And now Ella, Ella, and her fellas

We’re making a wreck, what a wreck of “Mack the Knife”

This is play, of course, but it’s also panic, an abandonment of control, a swirling, happy vortex that Ella invites her audience into. In that “wreck,” I hear a whole culture, maybe a whole planet, crawling out from under the shadow of two world wars, desperate for some entertainment, daring to hope for simple joy once again.

Don’t we all feel more than a bit cornered right now? Aren’t we desperate for some joy? What will life be after this virus? What threshold can we cross to delineate now from then? Will Trump’s infinite blathering loop begin to fade? Will the storm of other shoes dropping finally pass? Regardless of the outcome of the election, will we remember how to spend a bit of our time in the present? Waiting for the future is the opposite of listening to music.

I don’t begrudge anyone their momentary salves, even if they are self-destructive and temporary. Better to destroy oneself than to be destroyed by Twitter. There’s nothing to do now but wait and hope and try to keep the merciless unease in check between refreshes. Ella can’t fix it all, but she’s kind company.

Soon enough this particular wave of obsession—for Ella and her long career that stretched well into the heart of my childhood—will pass and I’ll be needling into something else, helpless against the gravity of John Zorn’s now out-of-print box set of all the Naked City albums (going for $75 on eBay), the Naxos edition of the complete re-recorded works of Arnold Schoenberg conducted by an aging Robert Craft (available in two box sets on Amazon), or the reissue of M. Ward’s Post-War on color-splattered vinyl available to members only from my LP-of-the-month club.

The election coincides with my 41st birthday. Time keeps yanking me along in its one damned direction, though this nether-region we find ourself in today is a hitch in the flow, and eddying place, a vortex, though not a joyful one. Can you blame me for leaning, however futilely, toward the past? Is it so lame to want, like Sylvia Plath huddling in her father’s ear in “The Colossus,” to fall asleep for eternity, or at least for the next few weeks—or months or years—nestled cozily between the discs of a comforting jazz box set, the liner notes crooning like a lullaby? “I have wasted my life,” wrote James Wright. Meanwhile, we must survive the election. Can I play you something beautiful?

Mack the Knife from Ella’s 1960 Live in Berlin LP:

“The Real American Folk Song”:

“Don’t Worry ‘Bout Me” from Easy Living:

Craig Morgan Teicher is the digital director of The Paris Review and the author of several books, including The Trembling Answers: Poems and We Begin In Gladness: How Poets Progress.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2HZHpUu

Comments

Post a Comment