William Beebe and Gloria Hollister inspect the bathysphere. © Wildlife Conservation Society. Reproduced by permission of the WCS Archives.

I’m writing from the outskirts of the small town of Tarapoto, in northeastern Peru. My ostensibly short trip here last March intersected with the declaration of a state of emergency: complete shutdown of domestic travel, strict curfew, international borders sealed. There were expensive “humanitarian flights” requiring government permission to travel to Lima; otherwise, it was impossible to move. This was meant to keep the virus out. By midsummer the situation improved elsewhere while Peru was suddenly in the global epicenter, and lockdown was meant to keep the virus in. Now the situation is reversing again, travel restrictions are loosening, and after eight months, I’m faced with the option of heading home.

Before the pandemic, I was living in Harlem, teaching at City College, and working on a book about the writings that remain from the bathysphere dives—strange, poetic texts that constitute the first eyewitness account of the deep ocean. The bathysphere was a four-and-a-half-foot steel ball fitted with circular, three-inch quartz windows, the first vessel that could go far underwater. Launching from the small island of Nonsuch, in the Bermuda archipelago, in 1930, the ball was winched off a vessel called the Ready and lowered on a steel cable. It eventually sunk to below three thousand feet, exponentially deeper than any previous dives.

Folded up inside the ball was William Beebe, a zoologist and popular nonfiction writer. When the dives began, he was already famous for his research on pheasants and his account of a recent trip to the Galápagos, where he’d witnessed the eruption of a volcano. His 1934 book on the bathysphere, Half Mile Down, straddles science writing, history, and a kind of secular mysticism, rich with observation but oriented toward the failure of language, the inexpressibility of experience.

I spent much of last winter in the basement of the Firestone Library in Princeton capturing Beebe’s personal papers—decades of his journals, correspondence, unpublished writings, notes and diagrams, fan mail from Rudyard Kipling (who prophesies submersible drones that stream video) and Arthur Conan Doyle (who wonders if Beebe has discovered Atlantis). Throughout most of the ensuing year, I sorted through these files, trying to make some order at a time when the world, and my life, were in disarray.

I’ve waited out this strange period in a little riverside lodge in the Amazonian Andes, a walled garden of hummingbirds and tamarin monkeys, tarantulas and poisonous ants. Along with the two owners and three staff members, I’ve lived mostly with four other New Yorkers: a molecular biologist, an ad agent, a psychotherapist, and a firefighter. We’ve had access to good food and decent Wi-Fi, and on hot, rainless days we could splash around in the river. As the viral outbreak and vile government wrought havoc in the U.S., we felt lucky to be here. Then, when police violence brought about mass protests, we wished we could march, too. By now it feels like this patch of high jungle is simply where we live, and the prospect of heading home is disconcerting. What are we going back to?

Among Beebe’s late-career notes, made in Trinidad, is a sheet that reads: “New type of Society. That of Wind.” He describes insects and other flying animals that aggregate on the lee side of a ridge during a gale: hawks and wasps and spiders, disparate creatures that otherwise do not spend time together, forced into partnership “by the blow which wrecks their attempts to fly.”

And I think: that’s us—locked down together until we form a family, immobile in the windblown shadow of a rock.

My first contact with Beebe’s writing was a fragment from Half Mile Down in which he describes one of the bathysphere’s first deep dives. He writes of his delight in witnessing bioluminescence—this was the first time anyone had seen the deepwater effects of animal light. He was thrilled to see so much life, so many unfamiliar species or species he’d only seen dragged up in a dredge.

But as much as his zoologist’s mind was taken with this sighting of marine animals, he was even more stunned by the effects of light and color. As he descended and the reds and oranges, all the warmer hues of the spectrum, were absorbed, the cool blue of the sea seemed to permeate his being. The bathysphere approached two thousand feet, the depth beyond which sunlight does not reach, and the blue seemed to intensify rather than fade into darkness. He was sure he could read by its light, until he glanced at a page and found it perfectly opaque.

This counterintuitive phenomenon bewildered Beebe. He sunk into a world seemingly created “of a single vibration.” Crawling out of the ball after surfacing, the scientist found himself once again in the familiar light of day. But the yellow of the sun, he wrote, “can never hereafter be as wonderful as blue can be.”

It was this sense of visionary encounter that inspired me to spend time with the bathysphere logbooks, three canvas-bound notebooks now stored in the basement of the Bronx Zoo. They contain the notes written by Beebe’s colleague Gloria Hollister, an accomplished scientist herself, who had developed a method of dyeing fish so as to see their internal structure without dissection. Hollister also made record-breaking dives in the bathysphere, but during most of the expeditions, she was aboard the Ready, listening to Beebe through a simple telephone, doing her best to note his faltering descriptions of what appeared outside the ball’s quartz windows:

1050 ft. blacker than blackest midnight yet brilliant

1150 beam of light showing clearly—light on.

1200 Idiacanthus. Two Astronesthes.

1250 Fish 5-inch-long shapes like Stomias

3-inch shrimps absolutely white

positive saw Argyropelecus in beam of light

2 luminous jelly pale white

1300 About 6 or 8 shrimps around

50 or 100 lights like fireflies

small squid in beam of light

seems to have no lights gone down for fish.

Cyclothones. Two-inch shrimps.

1350 Light very pale

temp. 72

1400 Looking straight down very black

black as hell

For Beebe, to look into the depths below, with the beam off, when there were no bioluminescent creatures to flash and display themselves, was to contemplate a darkness for which such words were inadequate. As he describes it in Half Mile Down, the blackness called all surface-world comparisons into question. As he sank, sometimes he simply repeated the word rhythmically to Hollister: “black, black, black, black.”

When he turned on the beam of the bathysphere, it shone a distinct yellow. At times he sat simply soaking in that color, trying to draw it into his being. But the moment the light switched off, it was as if it had never been. There had never been daylight, no streaks of illuminated clouds in twilight, or any relative darkness of a midnight in the jungle.

If the blue he encountered on the first dives was so blue as to permanently alter the yellowness of the sun, here was a black so black it called his very existence into question. This fecund and hungry vacuum split logic into impotent flagella, detached from the bodies they were meant to move. The comparisons of the human mind, its clawing after orientation, evaporated.

At such times he again remembered that he was alive, that barring an accident he would return to the surface, and that the only other humans who had entered these abyssal depths were the decomposed bodies of drowned sea-goers. He was truly on a trip through the underworld, an idea that had haunted humans for thousands of years. Now it was done, and reasoning about it, even talking about it, was useless.

But then a glow floated into view and pulsed with strange light. Stranger than anything he could have conceived. And in this illumination, the contour of a body emerged. A shape with fins or pulsing membranes, eyes or teeth or threadlike networks of tissue. And in his perplexity, he experienced the simple thrill of spotting a new species. He attempted to render it in language as best he could—“a Punch-and-Judy head, with a face which is no face”—before it swam away or drifted out of view. These sightings lit up his scientist’s brain with delight.

But still, he saw the frailty, even absurdity of his situation: the Ready rocking on the surf south of Nonsuch, a strand of steel and wire leading down through the vanishing reds and yellows to his lonely perch, sealed against the crushing pressure of the water, like a capsule in distant space about to be extinguished by a galactic explosion.

When he thought about it later, he concluded that his only contribution to science and literature was that he’d been able to testify: “At a depth of a quarter of a mile. A luminous fish is outside the window.”

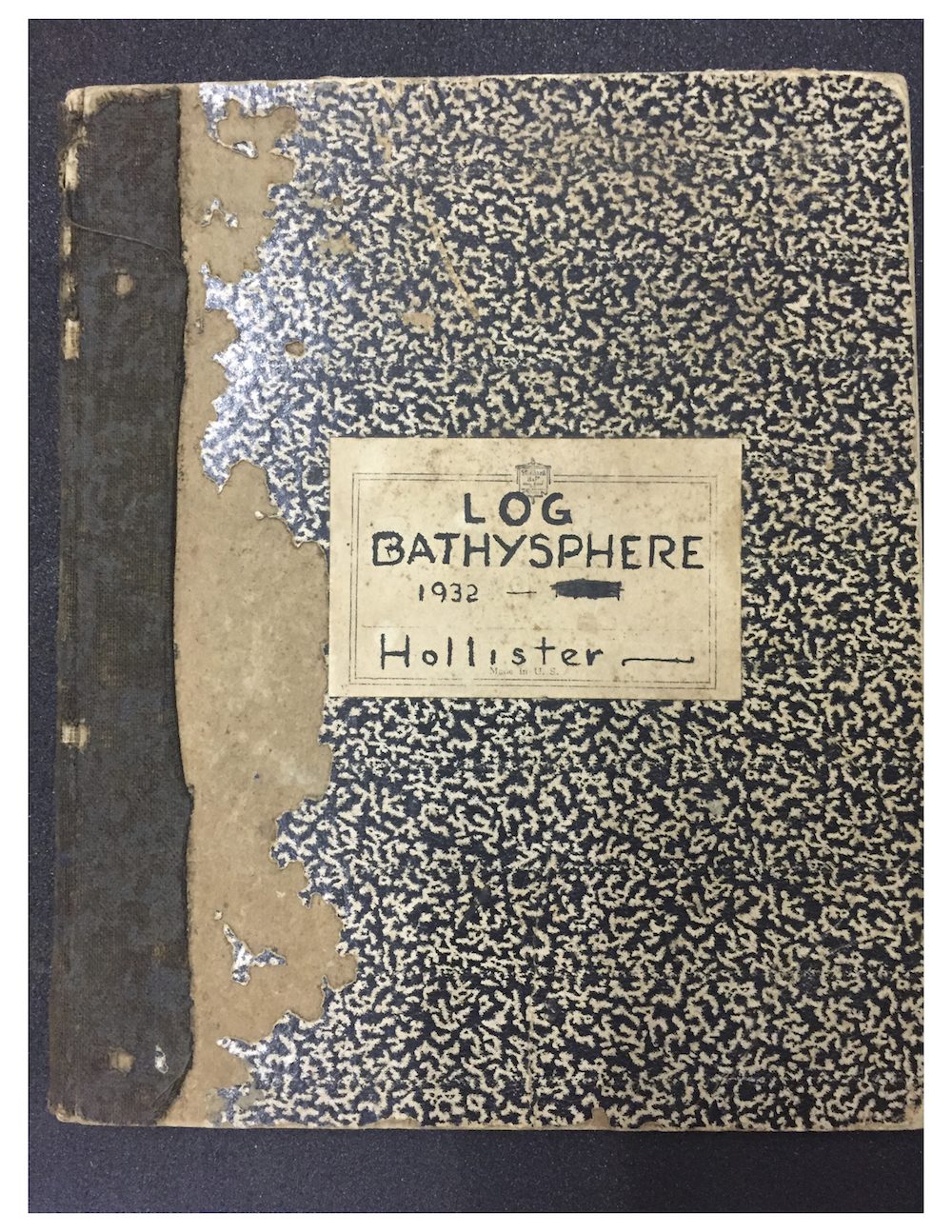

The 1932 logbook for Beebe and Hollister’s bathysphere expeditions. © Wildlife Conservation Society. Reproduced by permission of the WCS Archives.

Unmentioned in the logbooks and articles or in Half Mile Down is that Hollister and Beebe were lovers throughout these expeditions. I can’t help but feel the intensity of their connection, the sense of seeing together that Hollister’s notes record, an emotional charge that runs through their exchange, discovery shared through wire and cable.

The two had worked together before, but the bathysphere dives marked the pinnacle of both their collaboration and their ten-year relationship. They abandoned marine exploration after the expedition and soon went their separate ways. Hollister worked for a while mapping Guyana (then British Guiana), then returned to the U.S., eventually founding a preserve at the Mianus River Gorge in Bedford, New York. Beebe moved from place to place with a small staff, finally establishing a research station in the hills of Trinidad, where he could contemplate the society of wind.

He wrote book after book, and they were successful, sold and read and translated across the world. But there was a joke within them he was unable to laugh at: “All these words in type … but I have given no more idea of the real happening than if I had attempted a description of the single peacock, the one opal, the solitary sunset which I had seen and you had not.”

Beebe thought of this inarticulacy—the nontransferability of experience—as the “penalty man must pay for rushing into new dimensions.” There was just no substitute for being there, and even being there—what had happened? All of this set him circling a central mystery that at times contracted to the size of a fish’s glowing eyeball, at times expanded until he was unsure of the solid ground he stepped on through the island at night.

When he had seen the eruption of a volcano on the Galápagos, he knew that everything he had learned and studied was useless: “We had been brought close to the beginning of things—and this could not be written or spoken, hardly thought.”

Brad Fox’s first novel, To Remain Nameless, was published by Rescue Press earlier this year. His stories, articles, and translations have appeared in The New Yorker, Guernica, and the Whitney Biennial. From 1996 to 2011, he worked as a journalist, researcher, and relief contractor in the Balkans, Mexico, the Middle East, and Turkey. He teaches at City College in Harlem.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/361eNE0

Comments

Post a Comment