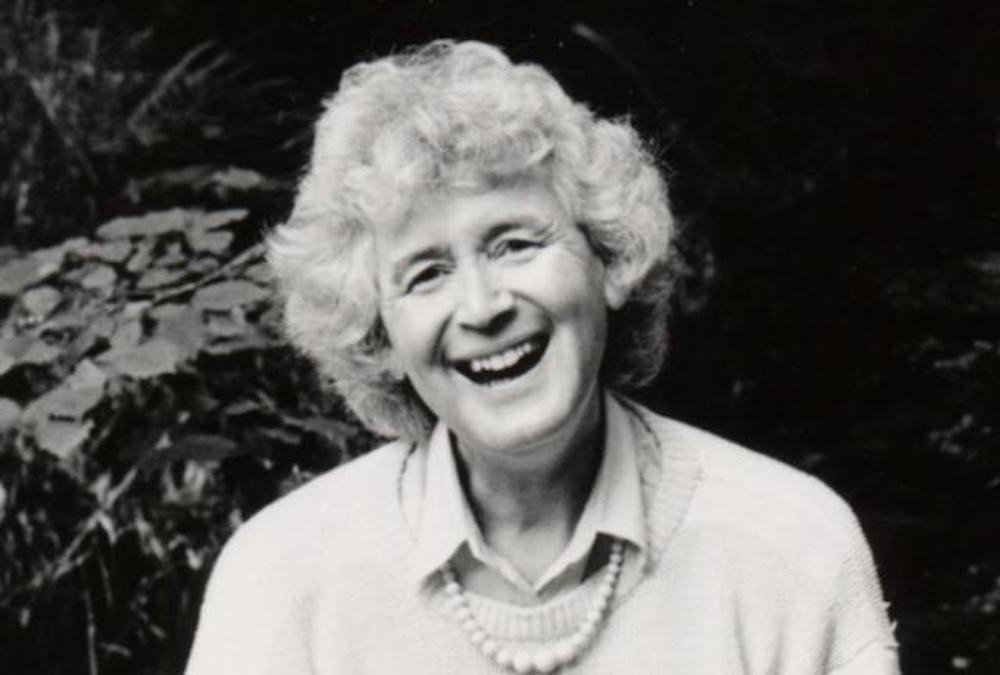

“To be writing about a place you’ve got to be utterly selfish,” said the legendary travel writer Jan Morris in her Art of the Essay interview. “You’ve only got to think about the place that you’re writing. Your antenna must be out all the time picking up vibrations and details. If you’ve got somebody with you, especially somebody you’re fond of, it doesn’t work so well.” Although Morris, who died Friday at the age of ninety-four, preferred to travel alone, her writing radiates the qualities of an ideal companion: knowledgeable, witty, relaxed, and always up for an adventure. If you pricked a globe with pins indicating the places she explored throughout her work—Venice, Hong Kong, wide swaths of South Africa and Spain, and, of course, Wales, where she lived for much of her life with her wife, Elizabeth—it would never stop spinning. Morris was nearly as adventurous in her literary endeavors as she was in her travels, publishing more than forty books of history, memoir, essays, diaries, and even fiction. In a foreword to the expanded edition of Morris’s novel Hav, Ursula K. Le Guin writes, “Probably Morris, certainly her publisher, will not thank me for saying Hav is in fact science fiction, of a perfectly recognizable type and superb quality.” Morris was also responsible for a groundbreaking account of her own gender confirmation surgery, Conundrum (1974). A tremendously insightful writer till the end, she in recent years published a selection of her diaries, an excerpt of which appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of The Paris Review. In these personal accounts of her days, Morris writes about walking her “statutory thousand daily paces up the lane,” keeping a frayed copy of Montaigne’s essays in her old Honda Civic, and spending days in the garden. One entry consists simply of a poem about her life with Elizabeth:

In the north part of Wales there resided, we’re told,

Two elderly persons who, as they grew old,

Being tough and strong-minded, resolute ladies,

Observing their path toward heaven or hades,

Said they’d still stick together, whatever it meant,

Whatever bad fortune, or good fortune, sent.

They’d rely upon Love, which they happened to share,

Which went with them always, wherever they were.

And if it should happen that one kicked the bucket,

Why, the other would simply say “Bother!”

(Not “F— it!” for both were too ladylike ever to swear .… )

Below, three of Morris’s longtime colleagues remember her charm:

My fondest memories of Jan Morris are of my visits to her home in North Wales. She and her wife, Elizabeth, lived for many years in a plas, a big house, and when this became too big they renovated the stable block and moved in there.

Wales mattered to Jan. In midlife, and at more or less the same time as her gender reassignment, she embraced what she called Welsh Republicanism. Her home, Trefan Morys, is in a remote area near the town of Criccieth. You leave the main road, take a long, rutted drive, negotiate the narrow entrance in a high stone wall, and you are suddenly in an enchanted space. Elizabeth was the architect of the garden and Jan the interior designer. You enter the house through a two-part stable door (Jan always greeting you with the words, “Not today, thank you”), into a cozy kitchen, and then the main downstairs room. The walls are lined with eight thousand books, including specially leather-bound editions of Jan’s own. Up the stairs there is another long room, with an old-fashioned stove in the middle. Here are more books, but this space is given over mainly to memorabilia and paintings. Pride of place is given to a six-foot-long painting of Venice, done by Jan, in which every detail of the miraculous city is rendered (including tiny portraits of the two eldest sons, who were very young at the time Jan painted it). Model ships hang from the ceiling, and paintings of ships adorn the walls. Jan loved ships from the time she spied them, as a child, through a telescope as they passed through the Bristol Channel near her family’s home.

In the bedroom, on the inside of a wardrobe door, is a full-length portrait of someone called John “Jackie” Fisher. Fisher was a legendary admiral-in-chief of the Royal Navy in the early part of the twentieth century. Fisher presented a haunting combination of “the suave, the sneering and the self-amused.” Jan wrote a book about him, Fisher’s Face, in which she stated that she would like either to have been Jackie Fisher or to have had an affair with him. She hoped to be able to have that affair in the afterlife, and now that she is gone, I’m sure she will. Jan loved to invite visitors into the bedroom, open the wardrobe door with a flourish, and stand next to her hero’s image. It was one of her many self-dramatizing but also self-mocking gestures.

The only portrait of Jan herself is a sculpted bust of her head, done by a friend, which stands on the deck outside the bedroom in one corner, and in the other is a bust of, yes, Jackie Fisher. The impression of egotism, benign and self-deprecating yet nonetheless very powerful, is evident throughout Jan’s house. Equally strongly expressed is Elizabeth’s modesty and self-effacement. Elizabeth always represented the safe haven that Jan could return to after her adventures. She is still alive, but when she dies their gravestone will read: “Here lie two friends, Jan and Elizabeth, at the end of one life.”

Jan was one of the great writers of her time, a wonderful exponent of English prose who fashioned a distinctive style that was elegant, fastidious, supple, and, at times, gloriously gaudy. It’s hardly an exaggeration to say that she imposed her personality on the entire world. I don’t think there will ever again be anyone quite like her.The story of her gender reassignment and the stories of her exploits as an ace journalist are fascinating, but in the end she was a writer.

—Derek Johns, Jan Morris’s literary agent for two decades, and the author of Ariel: A Literary Life of Jan Morris

Five years ago, when Jan was, I think, eighty-nine, I met her in Wales, and she drove me to lunch. She was a fantastic driver—impressively fast and skillful, not at all what you might imagine from an intensely thoughtful, softly spoken elderly woman. Along the way she told me an anecdote about her mother that was so funny and outrageous I am still not sure whether it was true, or whether she made it up on the spot to entertain me. Either way it is probably not printable. She was perhaps the best person I have ever met. Her spirit and ethos have guided and comforted me since before that drive, and they do still.

—Sophie Scard, an agent at Jan Morris’s literary agency

When I started working at Faber in 2000, as an editorial assistant, one of the first books I really got to work on was Jan’s masterful Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere. We somewhat fancifully billed it at the time as her final book (this may be apocryphal, but I’m pretty sure I remember Jan saying, with a smile, that it would be good for publicity). One year later I helped go through all of her work to compile A Writer’s World—her greatest hits, if you like, of fifty years of journalism and travel writing. Quite aside from delivering one of the greatest scoops of all time—successfully coding the news of Hilary’s conquest of Everest back to the Times in London to run on the morning of the Queen’s coronation—here was a writer who witnessed and reported on the Eichmann trial, the Suez Crisis, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Lewisham riots, and the handover of Hong Kong, among so many other landmark moments of the latter half of the twentieth century.

More recently, I was lucky enough to acquire and edit her final books—two volumes of diaries, In My Mind’s Eye and Thinking Again. Started in her ninetieth year, these not-quite-daily missives are quintessentially Jan Morris in tone—at once beautifully melancholic and delighted with life, with all its absurdities and blessings. They really are wonderful, written with her keen-eyed observation and acceptance of the fact that despite being one of the most traveled people in the world she wouldn’t be traveling beyond her own village again. There is also something else at play, lurking between the lines, a glint-in-her-eye quality that was ever present in her writing, from Coast to Coast in 1956 to Thinking Again sixty-four years later. I remember this quality well from real life, too, as anyone who met her or saw one of her memorable live readings may also. The last time I saw Jan in person was when her long-term agent, Derek Johns, and I visited her and Elizabeth at their home in Wales to deliver a finished copy of In My Mind’s Eye. We went out for dinner that night to her local pub, and on the way she said delightedly that they did the best homemade marmalade and she was going to treat me to a jar. When we arrived and she asked the landlord for two he informed her there was, sadly, only one left. “Sorry,” she said, taking the jar and turning to me with a smile, “this one’s mine, you’ll just have to come and visit again.”

—Angus Cargill, Jan Morris’s editor at Faber

Read Jan Morris’s Art of the Essay interview in our Summer 1997 issue

Read excerpts from Jan Morris’s diaries in our Summer 2018 issue

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3q5csQu

Comments

Post a Comment