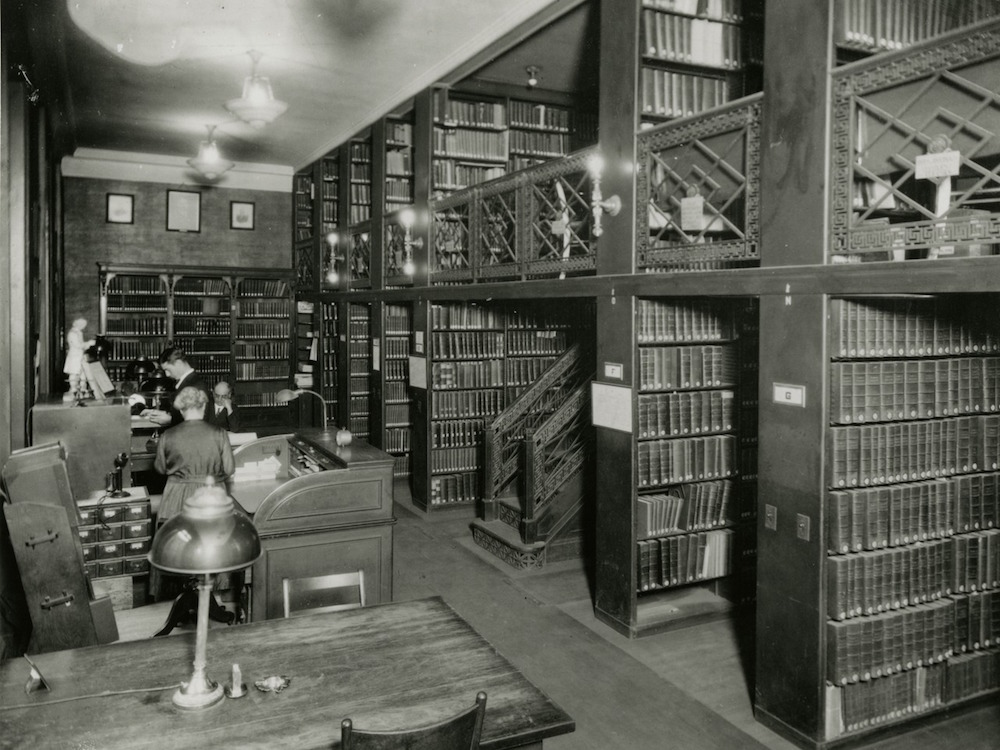

The Chemists’ Club library in New York, New York, ca. 1920. Photo courtesy of Science History Institute. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I was thirteen and wanted to work. Someone told me that you could get paid to referee basketball games and where to go to find out about such weekend employment. I needed income to bolster my collections of stamps and Sherlock Holmes novels. I vaguely remember going to an office full of adolescents queueing in front of a young man who looked every inch an administrator. When my turn came, he asked me if I had any experience and I lied. I left that place with details of a game that would be played two days later, and the promise of 700 pesetas in cash. Nowadays, if a thirteen-year-old wants to research something he’s ignorant about, he’ll go to YouTube. That same afternoon I bought a whistle in a sports shop and went to the library.

I wasn’t at all enlightened by the two books I found about the rules of basketball, one of which had illustrations, despite my notes and little diagrams, and my Friday afternoon study sessions; but I was very lucky, and on Saturday morning the local coach explained from the sidelines the rudiments of a sport which, up to that point, I had practiced with very little knowledge of its theory.

My practical training came from the street and the school playground. My other knowledge, the abstract kind, stood on the shelves of the Biblioteca Popular de la Caixa Laietana, the only library I had access to at the time in Mataró, the small city where I was brought up. I must have started going to its reading rooms at the start of primary school, in sixth or seventh grade. That’s when I began to read systematically. I had the entire collection of The Happy Hollisters at home, and Tintin, The Extraordinary Adventures of Massagran, Asterix and Obelix, and Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators at the library. Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie were devoured in both places. When my father began to work for the Readers’ Circle in the afternoons, the first thing I did was buy the Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple novels I hadn’t yet read. That’s probably when my desire to own books began.

The Biblioteca Popular de la Caixa Laietana acted as a surrogate nursery. I don’t think children today have to write as much as we did in the eighties. Long, typed-out projects on Japan and the French Revolution, on bees and the different parts of flowers, projects that were a perfect excuse to research in the shelves of a library that seemed, then, infinite and boundless; much greater than my imagination, then anchored in my neighborhood and still restricted to three television channels and the twenty-five books in my parents’ tiny library. I did my homework, researched for a while, and still had time to read a whole comic or a couple of chapters of a novel in whatever detective series I happened to be enjoying. Some children behaved badly; I didn’t. The twenty-five-year-old librarian, a pleasant, rather custodial type, who was tall, though not overly so, kept an eye on them, but not on me. I’d go to him when I needed to find a book I couldn’t track down. I also began to hassle Carme, the other young librarian, who saved us from her older, pricklier colleagues, with clever-clever, bibliographical questions: “Any book on pollen that doesn’t just repeat what all the encyclopedias say?”

I mentioned my parents’ micro-library. “Twenty-five books,” I said. I should explain that Spain’s transition from dictatorship was led by the savings banks. Municipal governments, busy with speculation and urban development, delegated culture and social services to the banks. Mataró was a textbook case: most exhibitions, museums, and senior centers, as well as the only library in a city of a hundred thousand inhabitants, depended on the Laietana Savings Bank. At the beginning of this century, during my (now real) research into Bishop Josep Benet Serra for my book Australia: A Journey, Carme, who has since become an exceptional librarian in Mataró, opened the doors of the Mataró holdings to me. I wasn’t then aware of that defining metaphor, the 2008 economic crisis hadn’t yet revealed the emperor’s nakedness: Mataró’s document holdings, its historical memory, wasn’t in the municipal archive, wasn’t in the public library, but in the heart of the Laietana Saving Bank’s People’s Library. During the Spanish transition to democracy, the so-called duty to look after culture was assumed by the savings banks without anyone ever challenging them; it only became evident when one of them published a book, which they sent to all their customers as a free gift. I have one in my library that I inherited or purloined from my parents’ house, Alexandre Cirici’s Picasso: His Life and Work. The title page says: “A gift from the savings bank of Catalonia.” It is the only institutional message. Although it’s hard to credit, there is no prologue by a politician or banker. There was no need to justify a gesture that was seen as natural. Over half of my parents’ books were gifts from banks.

Years later, a childhood friend of my brother died in a traffic accident. Consumed by grief, his mother told mine that there was a woman in her support group who carried a newspaper cutting in her purse. She took it out. She read it aloud. Those words made her feel proud of her son, whom she’d so missed since the accident had killed him, his wife, and their two children. Those words helped her to live without her grandchildren, the children of a librarian disguised as a friendly policeman. Those words, partly erased by all those I’ve written since, were mine for a short while: now they belong to newspaper libraries that are gradually disappearing, because it’s likely that, even for that mother, who will have partially overcome her grief, they are simply a memory. I’m not sure whether, in that obituary, I evoked those Saturday afternoons in a school playground, when I’d left the Mataró library for the library of the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, where the friends of the not-so-young librarian and my friends and I played basketball together.

*

The other day I went down to the library of the university where I work to look for a copy of André Breton’s Nadja, which I needed for a class, and which I couldn’t find in my own library. There it was, in the same place it must have been in 1998, when I read all the surrealist books I could find, interested as I was in their theories about love (and my practice of it): Mobile by Michel Butor. But I didn’t see it then. I did see it seven years later, in the University of Chicago Library, when I had the whole winter ahead of me to read. I sense that bookshops display the books in their possession in a seductive, almost obscene, manner because they want to sell them to you; conversely, libraries hide or at least camouflage them, as if they were content just to hoard. But it’s also true that it’s your gaze that scans the books’ spines, that it’s your attentiveness or whim that determines whether the titles and authors are revealed or go unnoticed.

The Pompeu Fabra University Library was very new when I started my first year in humanities. It was so young its sections didn’t even have names. As a library matures, it begins to house donations, collections, archives, each bearing the name of a donor, a scholar, or someone retired or dead. In relation to a library, we associate the verb “to exhaust” with Borges. I am someone who exhausts bookshops and libraries; I love to spend hours looking at sections, shelf by shelf; the books, spine by spine. I have done this on rainy days in many of the world’s cities. On snowy days, only in one: Chicago. I have never felt so lonely as in those weeks at the beginning of 2005. I came to spend twelve or thirteen hours in that enormous library. Before I discovered the interlibrary loan system that gives you access to any book in any library in the United States, I spent many hours in the Spanish literature section, in search of travel books and essay collections you can only find in that way, via the pre-digital google of meandering around a labyrinth of books. My Ariadne’s thread: all those titles and pages, their secret disarray. Loneliness; there is no worse minotaur.

Using a neophyte library like the one at my university, Chicago’s—and before that, the University of Barcelona’s—alerted me to a key cultural concept: holdings. That possible memory of a particular state of culture and the world. That fragment you will never fully know of a whole that can never be reassembled. Holdings are often bottomless pits, places where unpublished manuscripts and the most important letters can exist without being seen (or worse, read) by anyone. At the pit bottom of the University of Chicago’s history, or simply on the foundation stone of its book collection, we find the first of many names to come: William Rainey Harper. His erudition and pedagogical experiments reached the ears of Rockefeller, who promised him $600,000 to create a center for higher education in the Midwest that could compete with Yale. In the end, $80 million came the University of Chicago’s way, because, in addition to writing Greek and Hebrew textbooks, Harper was spinning strategies so that the poor, and those who worked full-time, could get access to higher education. He was an excellent manager. He created the university press that survives to this day. On the other hand, the William Rainey Harper Memorial Library was closed in 2009. The message on Librarything couldn’t be starker:

University of Chicago—William Rainey Harper Library

Status: Defunct

Type: Library

Web site: https://ift.tt/3hVk7Nc

Description: On June 12 2009, the William Rainey Harper Memorial Library was closed, and its collections transferred to Regenstein Library.

Defunct library. The demise of a library as the final death of an individual who survived almost a century after his actual death. It makes you think there’s no word more pretentious than university.

In one of his now forgotten articles about literature, which I finally read the other day in the Humanities library of the university where I work, Michel Butor writes: “a library offers us the world, but offers us a fake world, sometimes there are cracks, and reality rebels against books, through our eyes, a few words or even certain books, something strange that points to us and triggers the feeling that we are shut in.” I think he is right: a bookshop gives material form to the Platonic, capitalist idea of freedom, whereas a library is often more aristocratic and can sometimes be transformed “into a prison.” In our homes, thanks to, or through the fault of, bookshops, we imitate the libraries we have visited from childhood and construct our own bookish topography. Butor says: “By adding books we try to re-construct the whole surface, so windows appear.” In reality we add centimeters of thickness to the walls of our own labyrinth.

*

Until now I had often been unable to find dispensable books, ones you could almost do without, on my own shelves; but the day I couldn’t find Nadja, one of those novels I have regularly dipped into over more than ten years, like Don Quixote, Heart of Darkness, Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch, Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, or David Grossman’s See Under: Love, I was forced to start worrying. In his famous essay “Unpacking My Library: A Talk about Book Collecting,” the urban nomad Walter Benjamin says that any collection oscillates between order and disorder. The like-minded Georges Perec sets out, in Thoughts of Sorts, an unarguable principle: “A library that is orderly, becomes disorderly: it’s the example I was given to explain entropy and I have verified it several times experimentally.” I must admit that in the four-and-a-half years that have passed since I moved to a flat in the Barcelona Ensanche I have accumulated books, and the odd set of shelves, without reordering my library’s overall structure. And now everything is horribly chaotic.

The world’s logic is mimetic. Everything works by imitation. The originality of our personality is but a complex combination of options we have borrowed from various models over time. My library is a response to the void of my parents’ house: there are traces of all the public libraries I’ve visited since childhood. The other day I came across some photocopied pages of Paul Bowles’s diary, pages that bore the Caixa Laietana stamp. I also hoard the books I’ve bought from the University of Chicago Library, which periodically gets rid of books in a fleeting—weekend—conversion of the library into a second-hand bookshop. When I last moved house, I arranged my library by language tradition and remoteness of interest. I keep next to my desk books about literary theory, communication, travel, and the city. Two feet behind those books is Spanish literature, in alphabetical order. Opposite them, three or four feet away, world literature. You must walk to the adjacent room, the dining room, to access historical, film, and philosophical essays, biographies and dictionaries (made even more distant by their online versions). I keep comics and travel books in the passageway. And in the guest room, finally, Catalan literature, essays on love, my books on Paul Celan, several hundred Latin American chronicles, as well as two copies of each of the books I have written or contributed to. Logic and caprice intertwine in a library that has occupied different spaces as the number of books grows and visits to Ikea are made. The bookcases in the study are solid wood: my parents, who still believe in solidity, bought them with my money to house the prototype of this library when I went traveling in 2003. But the rest of the apartment is filled with Billy shelves bent under their load, and gradually coming apart as a result of my lack of dexterity, which condemned them to degeneration the moment I screwed them so poorly together; I may be a more or less competent reader, but I’m a hopeless DIYer. My childhood toys included a microscope, mineral and physics kits, as well as a toolbox: I hardly need to say I didn’t end up specializing in carpentry or the sciences.

“Every collection is a theatre of memories, a dramatization and staging of individual and collective pasts, of a childhood remembered and a souvenir after death,” Philipp Blom wrote in To Have and to Hold: An Intimate History of Collectors and Collecting, adding: “it is more than a symbolic presence: it is a transubstantiation.” All those books that surround me every day allow me to feel near to myself—to what I was, to that reader who kept growing, changing, adding layers—and to the information and ideas they contain. Or that they only suggest. Or that they only hyperlink: many of my books are planets orbiting around thinkers, writers, and historical figures I don’t know firsthand, but that are friends of friends, involuntary accomplices, shifting pieces in a complex system of potential knowledge.

Friends, acquaintances, future contacts. Those are the three labels around which I’m going to organize my library, I decide as I finish writing this essay, when we rearrange the house next month for happy, familial reasons. I will dismantle it in order to reinvent it. I shall place near me only those writers and books with which I enjoy a more or less close friendship. These will stay in (or will enter) the study. They’ll surround me, as their memory already does, or that of their authors. I will keep acquaintances in the dining room, the ones I respect and feel fondly toward. Most of the books I haven’t read, and that I don’t know if I ever will, will be given away and sacrificed; those that remain, in the passageway, will await their turn, patiently, distantly, like people you don’t know, whom you may never know.

Aby Warburg, founder of the twentieth century’s most fascinating library, placed a single word over the entrance: “Mnemosyne.” His books and prints moved and migrated according to dynamic relationships of affinity and sympathy, creating provisional collages and leaving it to readers to imagine the links between them. As far as he was concerned, a library’s only reason to exist was as a place where one could stroll and wander. In the stroller’s gaze, images and texts fired invisible arrows at each other: neuronal synopses: the electricity nourishing the history of form and art. “It’s not merely a collection of books, but a collection of problems,” said Toni Cassirer, the wife of German philosopher Ernst Cassirer, after paying it a visit: a library only has meaning if it soothes as much as it disturbs, if it resolves, but above all, poses riddles and challenges. Cohabiting with a personal library means that you’re not surrendering, that you will always have fewer books read than books left to read, that books that keep company with one another are chains of meanings, mutating contexts, questions that change according to tone and response. A library must be heterodox: only the combining of diverse elements, of problematic relationships, can lead to original thought. Many of those who saw Warburg’s library described it as a labyrinth.

In his introduction to Warburg Continuatus: The Description of a Library, Fernando Checa writes: “As a theatre and arena of the sciences, the Library is also a real ‘theatre of memory.’ ” Which is what this essay has attempted to be. “There will never be a door,” wrote Borges in a poem precisely entitled “Labyrinth,” “You are inside / and the castle encompasses the universe / and has neither obverse nor reverse, neither external wall nor secret centre.”

—Translated from the Spanish by Peter Bush

Jorge Carrión’s Bookshops: A Reader’s History, published by Biblioasis in 2017, was universally acclaimed and has appeared in thirteen languages. He is the author of three novels, including Los muertos, which won the 2011 Festival de Chambéry. Carrión’s journalism appears in the Spanish-language edition of the New York Times and many other newspapers in Europe and the Americas. He lives in Barcelona, where he is the director of the creative writing program at Pompeu Fabra University.

Peter Bush’s recent translations include Teresa Solana’s The First Prehistoric Serial Killer and Other Stories, his selection of Barcelona Tales from Cervantes to Najat El Hachmi, and Leonardo Padura’s Grab a Snake by the Tail. In press are Josep Pla’s Salt Water and Quim Monzó’s Why, Why, Why?; in process, Balzac’s The Lily in the Valley and a selection of Salvador Dalí’s letters. He lives in Oxford, UK.

Excerpted from Against Amazon and Other Essays. Used with the permission of the publisher, Biblioasis. Copyright © Jorge Carrión, 2019. Translation copyright © Peter Bush, 2020. Reprinted by permission of Biblioasis.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3l5m1Lw

Comments

Post a Comment