It’s hard to imagine now, but people once gathered together freely, shoulders rubbing against shoulders, breath exchanged between lungs, bodies open to one another—all this closeness, almost a million people, standing in a crowd, just to watch a statue get undressed.

It was a rainy late October day in 1886 and the Statue of Liberty was shrouded in a French flag. The weather was miserable and the ceremonial unveiling went poorly. The drapery was pulled off too soon (right in the middle of a speech), and the fireworks display had to be canceled and rescheduled. Still, over a million freezing New Yorkers came out (including a boat full of suffragettes, protesting the statue). While it’s hard for me to even imagine standing inside a crowd of that size, it’s harder still to imagine the Statue of Liberty herself, as she looked then. Before she was the verdigris icon, patron saint of many a bespoke paint color, she was copper-skinned. Brown, not green.

It felt like a revelation to read that tiny detail in Ian Frazier’s New Yorker piece on Statue of Liberty green. When the first residents beheld the Lady Liberty, they saw not an otherworldly aqua-skinned allegory holding her lit torch to the sky, but a metallic regal woman stretching upward from a granite plinth. It’s a simple enough fact, and yet I have trouble wrapping my head around it. Brown, not green.

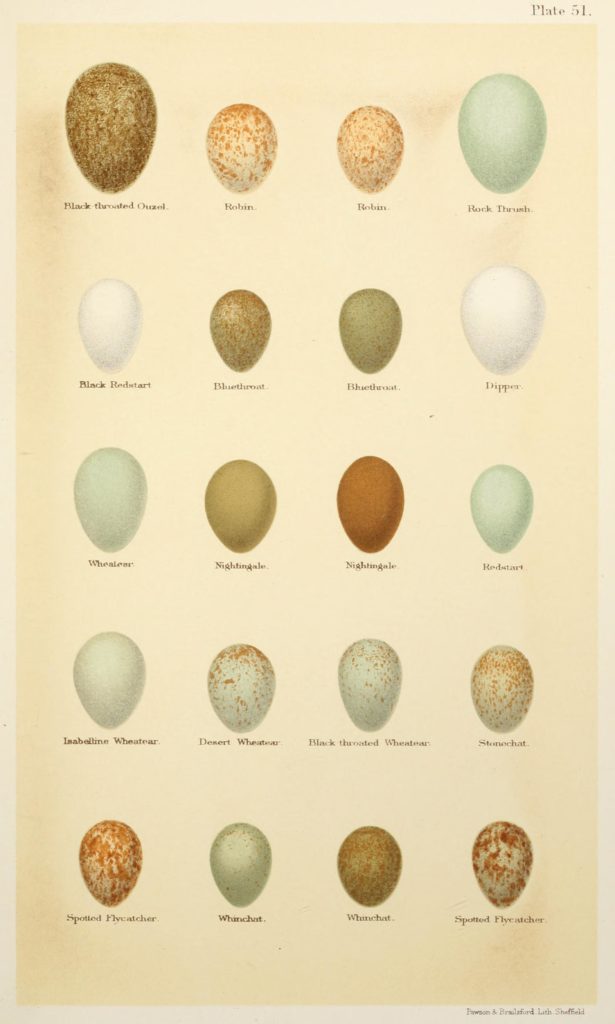

She was brown because that’s the color of copper, an interesting chemical metal that occurs frequently in nature in a usable form. She is green because that’s the color of verdigris, a substance that both is and isn’t turquoise. She’s green because we live surrounded by oxygen and when oxygen comes into contact with a metal like copper, it begins to tear away the electrons, which allows for the copper atoms to begin reacting with other particles. On the coast, uncoated metal can come face-to-face with harsh seawater, a substance that is naturally full of salt—ions and carbonic acid. Thus, the lady’s metal skin gains a thin, colorful coating made of copper chloride. This crystalline solid appears to the human eye as a light robin’s-egg blue, a turquoise patina, a soft hue somewhere between green and blue.

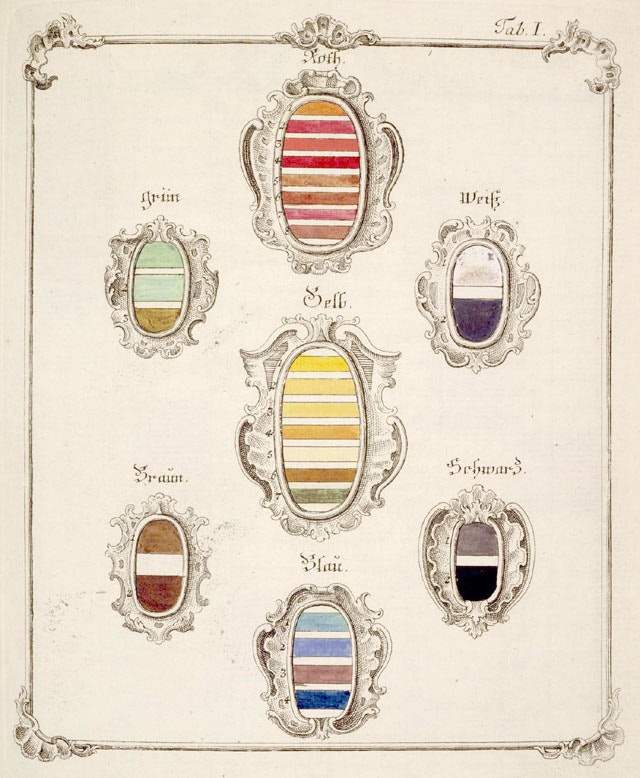

Next to the shifting and dated definition of millennial pink, the green-blue spectrum is perhaps my favorite color quandary. It’s a surprisingly loaded issue: where one ends and the other begins, and what to call the colors in between. For centuries, there was a myth circulating in white culture that the more words we had for colors, the more colors we could see. Since some cultures don’t have separate words for green and blue, some historians believed that the people who spoke those languages couldn’t see the difference, that their visual skills were lesser-than, that their abilities were less evolved than the cultures that named these leaves green, that pool blue. According to this logic, English speakers were superior because of our words for green and blue—not to mention our words for all those shades that exist in the gradient between them.

This is most likely not the case. People’s eyes work mostly the same around the world (save for notable exceptions, such as those who are visually impaired or color blind). The fact that we’re living in an increasingly color-literate world doesn’t mean we’re changing how we see. But we are changing how we look.

Since I became interested in colors a few years ago, I began amassing a mental collection of in-betweens. Colors that didn’t fall into a clear category. Colors that I felt were misnamed or misunderstood. The majority of them fell into the same bucket as so-called copper green. In here, I threw aqua, cyan, turquoise, teal, and Tiffany’s. I filed away glaucous and Cambridge blue. None of them were really blue and none of them are really green. I suppose they’re all shades of turquoise, yet that seems wrong, too. Turquoise is a relatively new name. Before there was turquoise, there was verdigris.

Verdigris is the ur-turquoise. The name comes an Old French term, vert-de-Grèce (“green of Greece”). It is also sometimes known as “copper green” or “earth green,” since the pigment was commonly made from ground-up malachite or oxidized copper deposits. Certainly, verdigris owes a great debt to copper (symbol: Cu), as does the gemstones turquoise (chemical composition: CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)8·4H2O) and malachite (chemical composition: Cu2CO3(OH)2). In America, we’re more likely to call these green-blue shades turquoise (from the Old French for Turkish, or “from-Turkey”) or Tiffany Blue (coined in 1845 with the publication of the Tiffany’s Blue Book catalogue and trademarked in 1998) than we are to invoke old-timey verdigris. Yet I prefer the odd old name with its vivid consonants and slithery tail. The word sounds unstable, fittingly fluid for such a liquid hue.

For many hundreds of years, verdigris was the most brilliant green readily available to painters. In the Middle Ages and during the Renaissance, artists commonly manufactured verdigris by hanging copper plates over boiling vinegar and collecting the crust that formed on the metal. This was mixed with binding agents, like egg white or linseed oil, and applied to canvas, paper, or wood. While not all of these famous works have been chemically analyzed, verdigris can reportedly be seen in paintings by the likes of Botticelli, Bosch, Bellini, and El Greco. But like Lady Liberty, who started as brown and lightened to green, many of these works have morphed over the years, their bright hues fading from saturated cyan or emerald (depending on how the color was mixed) to murky grays and pond-water browns. For verdigris is both toxic and unstable, a fact that Leonardo da Vinci knew, though he persisted in using it still. (“Verdigris with aloes, or gall or turmeric makes a fine green and so it does with saffron or burnt orpiment; but I doubt whether in a short time they will not turn black,” he wrote.) It was just such a beautiful color, and so readily available. It was hard for painters to resist, even when they knew it would render their works mortal. To use verdigris was to accept that your lovingly rendered scene would one day sour. The bright cloaks would turn dark, the soft grass would fade, the foliage turn. But such is the nature of cloth and plants and paint. Such is the nature of beauty.

Of course, it is possible to restore a painting. Sometimes, when a painting is restored, the conservationists use synthetic pigment to retouch areas where the color has faded or changed. This was the case with Jan van Eyck’s Margaret, the Artist’s Wife, which hangs in the National Gallery in London. “Following cleaning the small losses and areas of damage needed to be retouched so that they do not distract from the compelling image and from Van Eyck’s immaculate painting technique,” writes Jill Dunkerton in her report on the process. “The materials used for the new restoration have to be stable, not changing colour like the old varnish and retouchings, and they must remain easily resoluble so that the painting can be safely cleaned again in the future. Carefully selected and tested modern synthetic resin paints are therefore employed.” While in some cases, the restored painting can look alarmingly different from the one we’re used to seeing (like with that ghastly Ghent lamb), Margaret doesn’t. She looks nice after her spa treatment—refreshed and pink. Her green accessories don’t look overly bright either, nor has her headdress been ruined. The National Gallery’s painstaking work paid off, and were Van Eyck around to see it, he might be quite pleased.

Yet there is something uncanny about even the most well-done restoration, just as there’s something strange about seeing pictures of the Statue of Liberty with her original copper coloring. Lately, I’ve found myself becoming increasingly skeptical about the value of authenticity as a goal. According to the logic of our time, it is important to be “real”. What is real? Real is authentic, unadorned, unchanged. Often, the “real” meaning is the primary one. What something really means is what it meant according to traditionalists. This argument has big implications when it’s applied to things like the Bible or the Constitution. When applied to art, the stakes are much lower. But the logic still feels strange. It discourages appreciation for change, for the slow evolution of things. Lady Liberty isn’t “really” brown. She’s both brown and green and gray and a multitude of other colors. Greek temples weren’t “really” colorful. They were once colorful and now that’s gone and maybe someday they’ll be colorful again, if that’s the will of the people.

I’m guilty of insisting on primacy myself, I know. At times, I’ve argued for the real definition of a color. But I also like how colors change, how words change, how material things age. Wood expands and contracts, copper gets weathered by the sea, and color words move through cultures. What we call “mauve” wasn’t what Victorians considered mauve. Same with puce. Same with so many other hues. Verdigris is emblematic of that movement. It’s a blue-green, yes. But more importantly, it’s a quality. It is hard to give it a hex code because it’s not flat. It’s a color made from change.

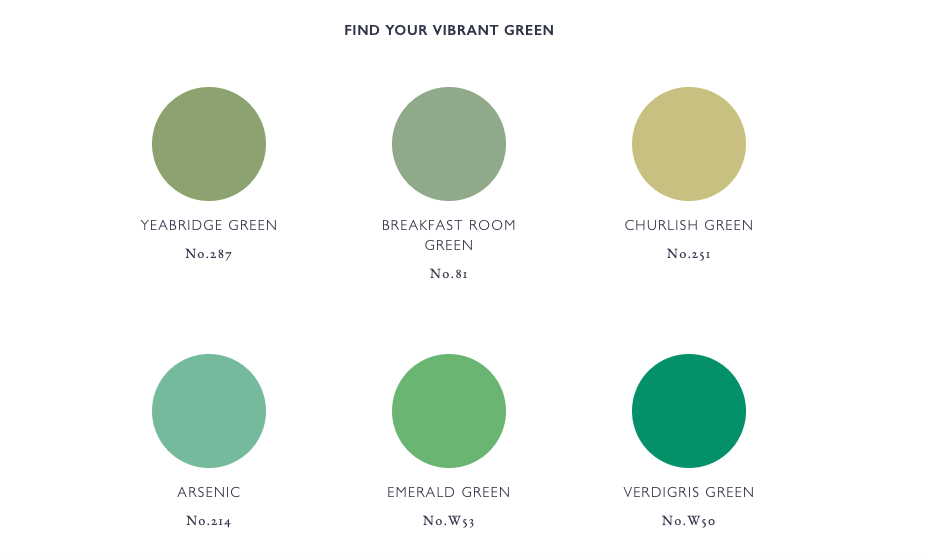

My recent interest in verdigris was piqued by the newfound ubiquity of Farrow and Ball colors, including the saturated teal they’re calling Verdigris. You might notice that I wrote colors there and not paints. Farrow and Ball is a high-end paint brand that has been profiled in the New Yorker and spoofed on SNL. It’s a subtle status marker that indicates a level of refinement in one’s private sphere. The paint itself isn’t really everywhere; I’ve seen it used in some house projects but it’s not as common as you might think. Being able to name-check a Farrow and Ball hue indicates that you’re in possession of a certain level of cultural capital. It’s also a funny kind of capital, because you don’t have to spend money on Farrow and Ball to gain access to this rarefied sphere. A few interior designers have confessed to me that they use Benjamin Moore dupes for Farrow and Ball hues in their personal homes, since it’s virtually impossible to tell the difference. The paint isn’t the point—it’s the name that matters.

And Farrow and Ball names are very, very good. Some are whimsical and child-like (like Mole’s Breath or Mouse’s Back), some are charmingly old fashioned (Lamp Room Gray or Wavet, named for “old Dorset term for a spider’s web”), a few are winter vegetables (Cabbage White, Brassica, Broccoli Brown), a few are obviously fancy (Manor House Gray, Mahogany), and many are simply obscure (Incarnadine, Dutch Orange, and Verdigris). Reading through the list reminds me of when I was a child, browsing J. Crew catalogues for overpriced sweaters, wondering what kind of woman would wear a harvest grape cashmere shell or a dusty cobblestone merino turtleneck. It has the same preppy, old money allure. A person who would paint their bedroom Brinjal (“a sophisticated aubergine”) probably spent their childhood in a house with a drawing room, summering in some coastal region I’ve never heard of, and capering about in child-sized loafers. They’re a competent sailor. They have never applied for Obamacare.

Plenty of paint companies have hues named for the color of salt water-aged metal, including Donald Kaufman’s “Liberty Green”, Benjamin Moore’s “Lady Liberty”, Sherwin Williams’ “Parisian Patina”, and Behr’s “Copper Patina”. And while once I might have argued that one paint color is more correct, I don’t want to do that. Farrow and Ball’s verdigris is no less real than Behr’s. It’s also no more true.

Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, Presentation Drawing of “The Statue of Liberty Illuminating the World,” 1875

I like verdigris, and all these greeny, eggy blues, because it reminds me that Tiffany doesn’t own turquoise. Neither do the mine owners in Colorado who are trying to brand their turquoise, nor the silver company that bought up all the stones from a single town. You can own a stone and you can patent a color, but you can’t own the word or the meaning. The minute you try, you lose something.

Over a hundred years ago, the United States Army began looking into turning the Statue of Liberty back to her original copper color. “As might be expected, when the Statue of Liberty turned green people in positions of authority wondered what to do,” writes Frazer. “In 1906, New York newspapers printed stories saying that the Statue was soon to be painted. The public did not like the idea.” In the end, nothing was done. Change was accepted, and we let her green skin stay. And like a word moving through years, shifting its meaning, she continues to change, ever so slightly. As an architect told Frazier, verdigris is not opaque. It is “crystalline… you’re looking into it.” You’re seeing a century of change and molecular growth. You’re seeing into the past. There’s brown. There’s green.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2UY1tda

Comments

Post a Comment