Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re resolving to read even more of our archive in the new year. Read on for Octavio Paz’s Art of Poetry interview, Rachel Cusk’s “Freedom,” and Margaret Atwood’s poem “Winter Vacations.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full sixty-seven-year digital archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!).

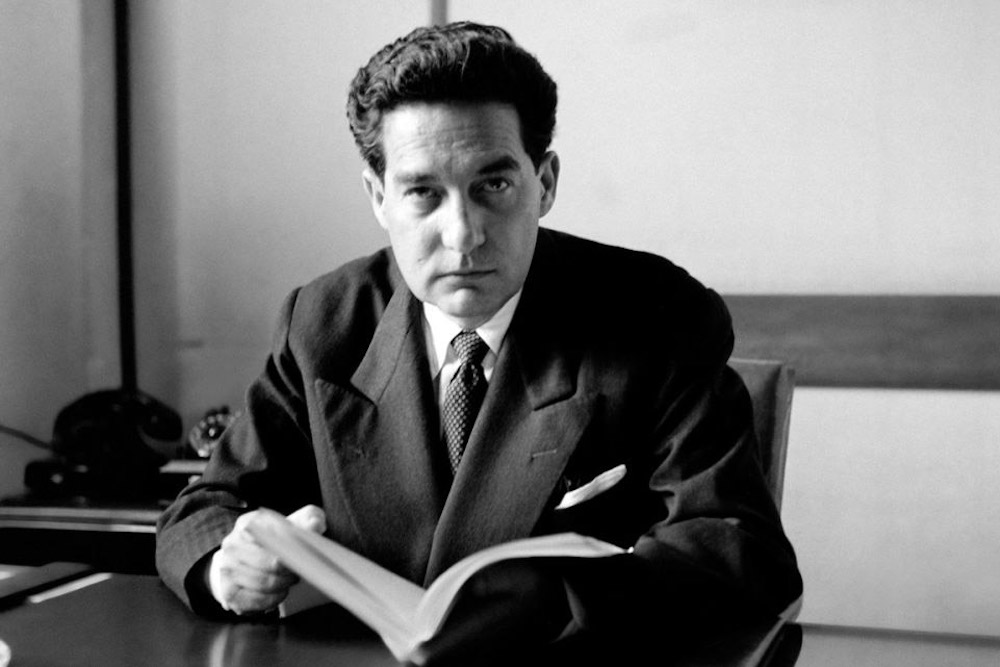

Octavio Paz, The Art of Poetry No. 42

Issue no. 119 (Summer 1991)

I am very fond of fireworks. They were a part of my childhood. There was a part of the town where the artisans were all masters of the great art of fireworks. They were famous all over Mexico. To celebrate the feast of the Virgin of Guadalupe, other religious festivals, and at New Year’s, they made the fireworks for the town. I remember how they made the church facade look like a fiery waterfall. It was marvelous.

Freedom

By Rachel Cusk

Issue no. 217 (Summer 2016)

“What’s it called,” Dale said, “when you have one of those bloody great blinding flashes of insight that changes the way you look at things?”

I said I wasn’t sure: a few different words sprang to mind.

Dale twitched his paintbrush irritably.

“It’s something to do with a road,” he said.

Road to Damascus, I said.

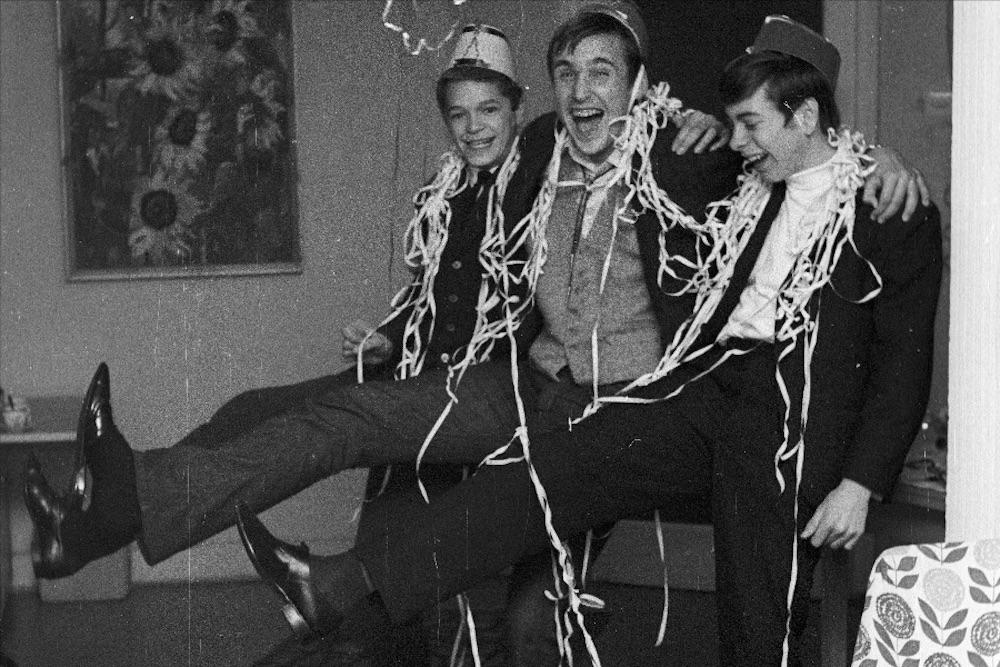

“I had a road to Damascus moment,” he said. “Last New Year’s Eve, of all times. I bloody hate New Year’s. That was part of it, realizing that I bloody hated New Year’s Eve.”

Winter Vacations

By Margaret Atwood

Issue no. 234 (Fall 2020)

… Despite all this we’re traveling fast,

we’re traveling faster than light.

It’s almost next year,

it’s almost last year,

it’s almost the year before:

familiar, but we can’t swear to it.

What about this outdoor bar,

the one with the stained-glass palm tree?

We know we’ve been here already.

Or were we? Will we ever be?

Will we ever be again?

Is it far?

And to read more from the Paris Review archives, make sure to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-seven years’ worth of archives. Or take advantage of our new subscription bundle, bringing you four issues of the print magazine, access to our full archive, and our new TriBeCa tote for only $69 (plus free shipping!).

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/37VfteP

Comments

Post a Comment