As much as there are perfectly crafted lines of poetry I think about often, there are perfect titles, too, that I find myself thinking about as much as the poems themselves. Recently, variations of the title “You, Very Young in New York,” the first in Hannah Sullivan’s Three Poems, have been at the front of my brain—looking at old photos from old summers, making future plans, bestowing this very young in New York phase of my life with the dynamic cadence of the phrase. Though corporeally I am still in a body that is still in New York, that cadence seems to belong to a past or future self that I sometimes feel I have to go back in search of or somehow move toward. Yet Sullivan’s poem dispels this notion. While it overflows with precise detail and indulges each of the senses spectacularly, the poem makes space for slowness, too. From the first page, the reader is invited to embody the second-person narrator—to hail their cabs, to wait for age to wear down a type of unwelcome innocence. Even then, “the senses, laxly fed, are self-replenishing, / Fresh as the first time, so even the eventual / Sameness has a savour for you,” which is a gorgeous comfort to imagine now. The sumptuousness of the poem, then—the vivid colors and tastes of huckleberry jam or overripe peaches “sitting with their bruises”—happens not despite the quiet moments but inside them. The second poem, “Repeat until Time,” lets the days stretch out even more. There, “days may be where we live, but mornings are eternity. / They wake us, and every day waking is an absurdity.” I’m learning from Sullivan how to thank the sameness for its savour, to wake to the absurdity as well as the sun. “‘You will know when it’s time, when the fair is over,’” says the opening stanza of the collection, and by the time the poem ends, it still isn’t over, but “through tears, you are laughing.” —Langa Chinyoka

Audacious is the word that kept coming to mind as I read Katharina Volckmer’s debut novel, The Appointment. Audacious, along with hilarious and unsettling—but unsettling in the best kind of way. The Appointment is a book about shame, of both the national and psychosexual varieties, and takes the form of a monologue from a young German woman in London to her Jewish doctor. Volckmer is quick to deflate contemporary Germany’s image of itself as a country that has dealt with its past, and she’s prone to lines that are as provocative as they are funny (“It’s possible that he also thought I was Austrian; Germans don’t usually bother with basements—they are happy to torture people on the first floor, they’re not that discreet”). This is a smart, unruly novel, one that dares to ask unexpected questions about the meaning of nation, gender, sexuality, and history. —Rhian Sasseen

The first installment of Bijan Stephen’s column for The Believer concerns a year spent immersed in the worlds of video games: “Embodiment in games acts as a surrogate for travel: I go somewhere else, somewhere that doesn’t necessarily intersect with the physical plane we inhabit.” In the early months of the pandemic, I often relied on music—specifically, the act of obsessive listening—to achieve a similar effect. I would lock myself inside musical fugue states, the anxious minutes melting into hours of Neil Young, mornings marked by nothing more than the same three Charli XCX songs, and whole afternoons ticked away in the comfortable quiet of Brian Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports. But more than anything else, I listened to 100 gecs, a duo perhaps best defined by their defiance of easy categorization. They make music that sounds like Crazy Frog executing a flawless breakdance routine within the confines of the Large Hadron Collider. On their 2019 debut album, 1000 gecs, 100 gecs split the atom of the past twenty years of popular music, leapfrogging from metalcore to dubstep, pop punk to hyperpop, ska to trap and back again. I may not have left my apartment much this year, but each dizzying trip through 1000 gecs jolted me out of my quarantine-induced stupor, leading me out of the physical world and into an imaginary space of ever-shifting dimensions and non-Euclidean geometry—towering walls of 808s, trees filled with digitized chirps, and everywhere the heavy gauze of autotune like a summer rain. Listening to 100 gecs can feel like literally surfing the endless expanse of the internet, gliding across the surfaces of depths both knowable and not, stumbling upon motifs and memes entirely divorced from context but constituting a landscape in and of themselves. In a stale, dark year, I find their omnivorousness—their appetite for adventure, their commitment to cultivating and then thriving within a galaxy of one’s own, as we all happen to be doing at this very moment—absolutely inspiring. —Brian Ransom

Because I’m simply obsessed with their work, I have to talk about the orchestral album that Supergiant Games has released in celebration of their ten-year anniversary. As you might have guessed thanks to my incessant praise for Supergiant, I have not stopped listening to their in-house composer Darren Korb’s divine work since the studio posted the entire album to YouTube—as they kindly do with all their music. Taking center stage are the mythical bardic ballads of Pyre and the “old-world electronic post-rock” of Transistor, which pair unexpectedly well despite their disparate genres. It’s no mystery that this is not just because of Korb’s brilliance as a musician but also Ashley Barrett’s inimitable voice work and Austin Wintory’s inspired conducting. To top it all off, the album was recorded at Abbey Road Studios. If you’re still uncertain about the legitimacy of music made for video games, please give a listen to “Paper Boats” or “The Vagrant Song”; there’s a quality of belonging to a different world that these songs not only magnify but celebrate in a way that is utterly unique. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

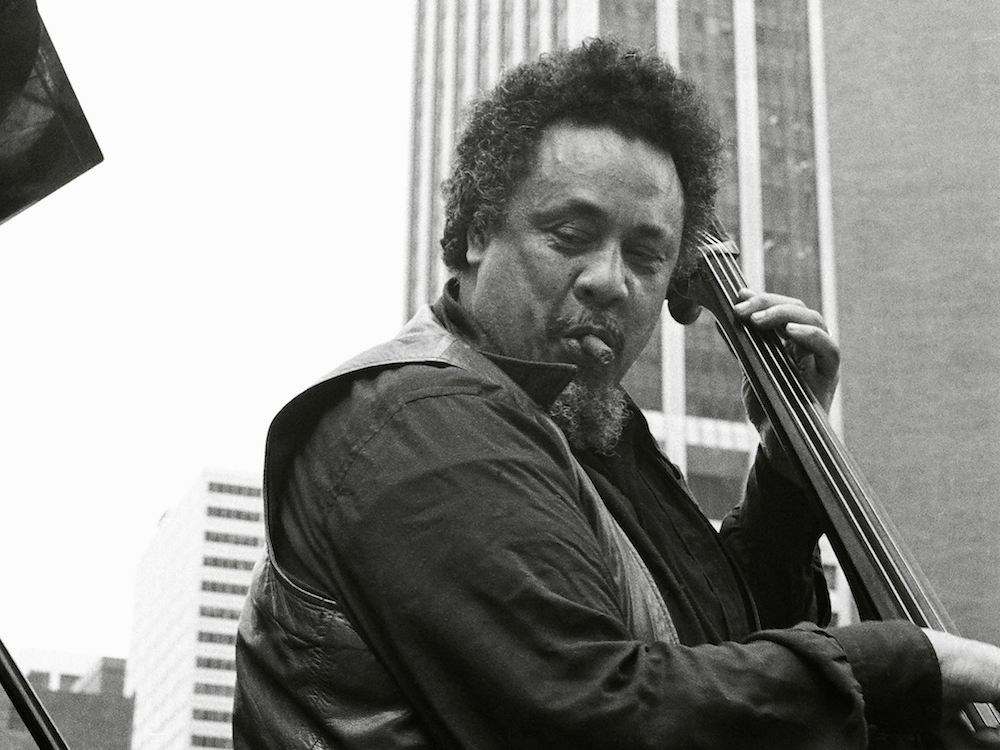

Charles Mingus was one of jazz’s most distinctive composers, writing musical odysseys in carefully plotted forms that leave plenty of space for dense collective improvisation. Charles Mingus @ Bremen 1964 & 1975, a new four-CD set (if you still go in for that sort of thing—you know, a thing), allows for the delicious and speculative pleasure of charting the course of a major artist’s development; it combines two live recordings made by Germany’s Radio Bremen a decade apart. The first is from 1964, at the apex of Mingus’s golden period; the other is from 1975, when his late music was at its fullest flowering. The 1964 band was one of Mingus’s best, featuring Eric Dolphy, Jaki Byard, and Johnny Coles, among others. Like Frank Zappa, my vote for his closest musical cousin, Mingus’s real instrument was not the bass but the band. His 1964 group races through what would become Mingus’s best-known music—including “Fables of Faubus” and “Parkeriana”—with all the abandon it demands. By the time of the 1975 concert, Mingus had largely left that wonderful controlled chaos behind in favor of the more polished, choreographed, and grandiose master class on jazz history that is his late music (as well as a reprise of “Faubus”). This is also, perhaps, some of Mingus’s most nakedly emotional and confessional music, if one wants to hear it that way. There’s a lot of live Mingus out there, but I’d wager no fan will regret adding this set to their shelf. —Craig Morgan Teicher

Charles Mingus, 1976. Photo: Tom Marcello Webster. CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://ift.tt/UbRXBT), via Wikimedia Commons.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3onVVFt

Comments

Post a Comment