In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive selections below.

“ ‘O winter closing down on our separate shells,’ Diane di Prima writes in her poem ‘Rondeau for the Yule.’ As many of us have been ensconced in our separate shells for most of this year—and as many East Coasters got a white shell of snow to cap that of the pandemic—Di Prima’s closing line struck a loud chord in this reader. With the year winding down, I felt another peal at Eavan Boland’s ‘Inscriptions,’ a poem that begins in ‘holiday rooms’ but cannot ignore ‘the deaths in alleys and on doorsteps, / happening ninety miles away from my home.’ Beyond their prescience, these poems are notable in that both of these poets passed away in 2020. In this time of incalculable loss, I wanted to conclude the year’s Art of Distance with work from some Paris Review contributors to whom we said goodbye this year. Whether you’re spending the holidays with family or with a good book, I hope this reading, and remembering the remarkable work of these writers, brightens the weeks ahead. We’ll be back in January.” —EN

Marvin Bell: “Then it is dark. The great streak of sunlight / that showed our side of snowy peaks has gone ahead.”

Eavan Boland: “To write about age you need to take something and / break it.”

Kamau Brathwaite: “Now bones once soft become rumble.”

Diane di Prima: “We are built for the exotic, we americans, this landscape leaves us / as open as a piece of chocolate cream pie.”

John le Carré: “I play around endlessly with the beginning and the middle, but the end is always a goal.”

Derek Mahon: “Let’s just say that you must, in order not to go mad, be able to speak.”

Michael McClure: “We are survivors / of the Future.”

Jan Morris: “I thought that the restlessness I was possessed by was, perhaps, some yearning, not so much for the sake of escape as for the sake of quest: a quest for unity, a search for wholeness.”

Lisel Mueller: “What I see is an aberration / caused by old age, an affliction.”

Kęstutis Navakas: “you’re home. eating lentils. talking to your / loved one. you’re abroad. eating lentils. talking to / your loved one. you’re not yourself. you’ve been stolen.”

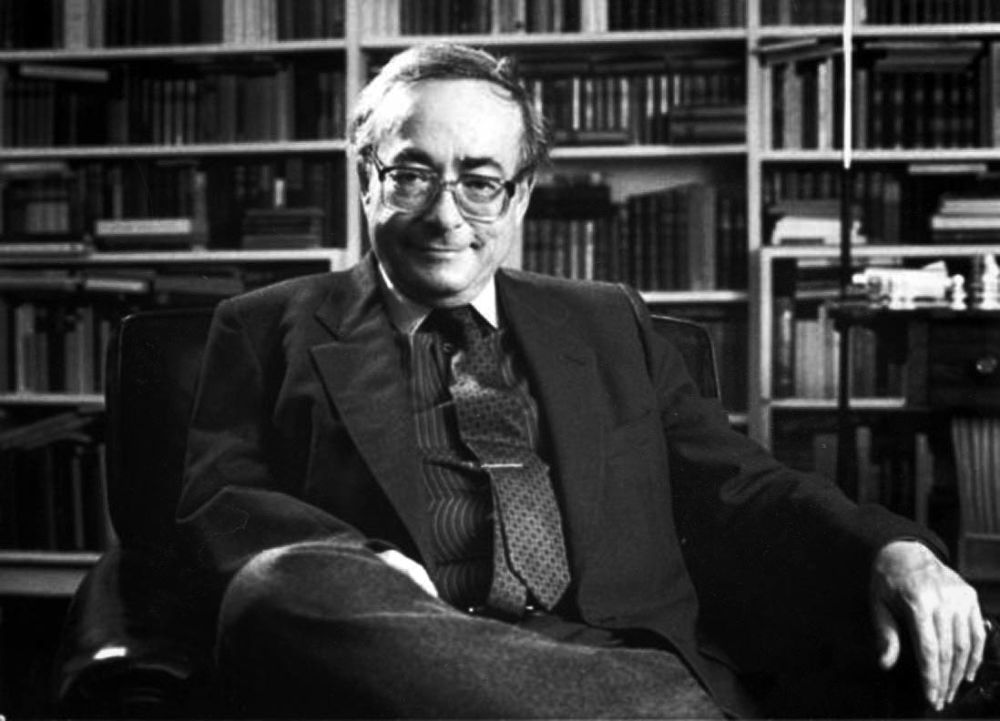

George Steiner: “The exciting distance of a great interpretation is the failure, the distance, where it is helpless. But its helplessness is dynamic, is itself suggestive, eloquent and articulate.”

Anne Stevenson: “Hug me, mother of noise.”

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3p5Ylce

Comments

Post a Comment