We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

I took one English class in college. The theme was contemporary fiction and, dutifully enough, we read DeLillo, Nabokov, Zadie Smith, Beckett, Coetzee, and—this last author was not like the others—Marilynne Robinson, whose novel Housekeeping appeared midsemester like a kind of anachronism. It was markedly domestic, reserved, inflected with lyricism, not self-serious but definitely sincere in its wonderment. At its first appearance, in 1980, spellbound reviewers praised its humble poetry, its interest in the ephemeral, the fidelity to small-town life.

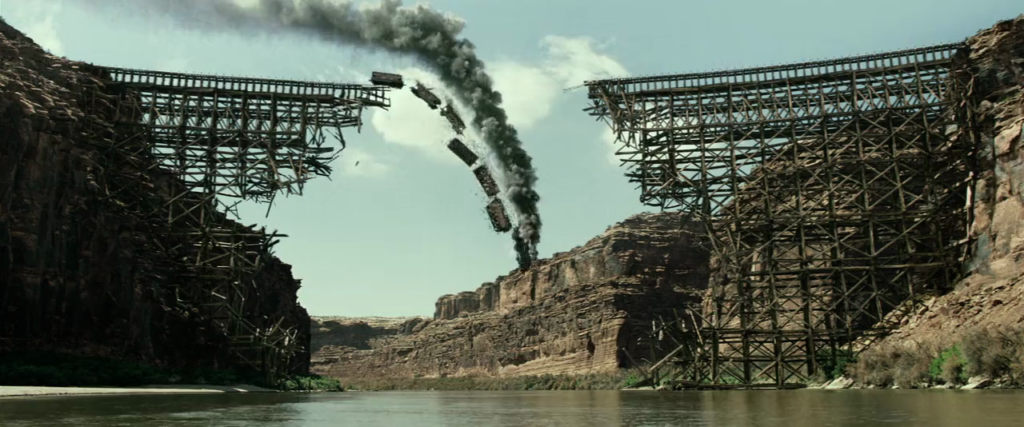

Housekeeping, now nearing its fortieth anniversary, has returned to me throughout my writing career. Like those enraptured critics, in my first encounters I read for language, for voice, for craft. I loved this book. In graduate school, in a seminar on the literature of travel and trains, my professor recited the opening line to the class with a kind of disgusted glee: “My name is Ruth.” What kind of beginning was this? How had such an otherwise beautifully written book gotten away with it? The declaration—harsh, direct—is perhaps more shocking in the context of the rest of the novel, which proceeds with the gentle indifference of understatement. That opening chapter describes a mass drowning as no more upsetting than an exploratory dive: a train “nosed” into a lake, Ruth tells us, as calmly as a “weasel,” claiming all the passengers within as the water “sealed itself” over their souls. The scene is so soft, so seductive, it may as well have been narrated by a ghost. I remember we spent the remaining hour of that class discussing whether drowning truly was the most romantic way to die. I wonder now if perhaps parting from one’s body becomes more appallingly beautiful when alibied by the suggestion of an afterlife.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/34ROZsR

Comments

Post a Comment