We’re away until January 4, but we’re reposting some of our favorite pieces from 2020. Enjoy your holiday!

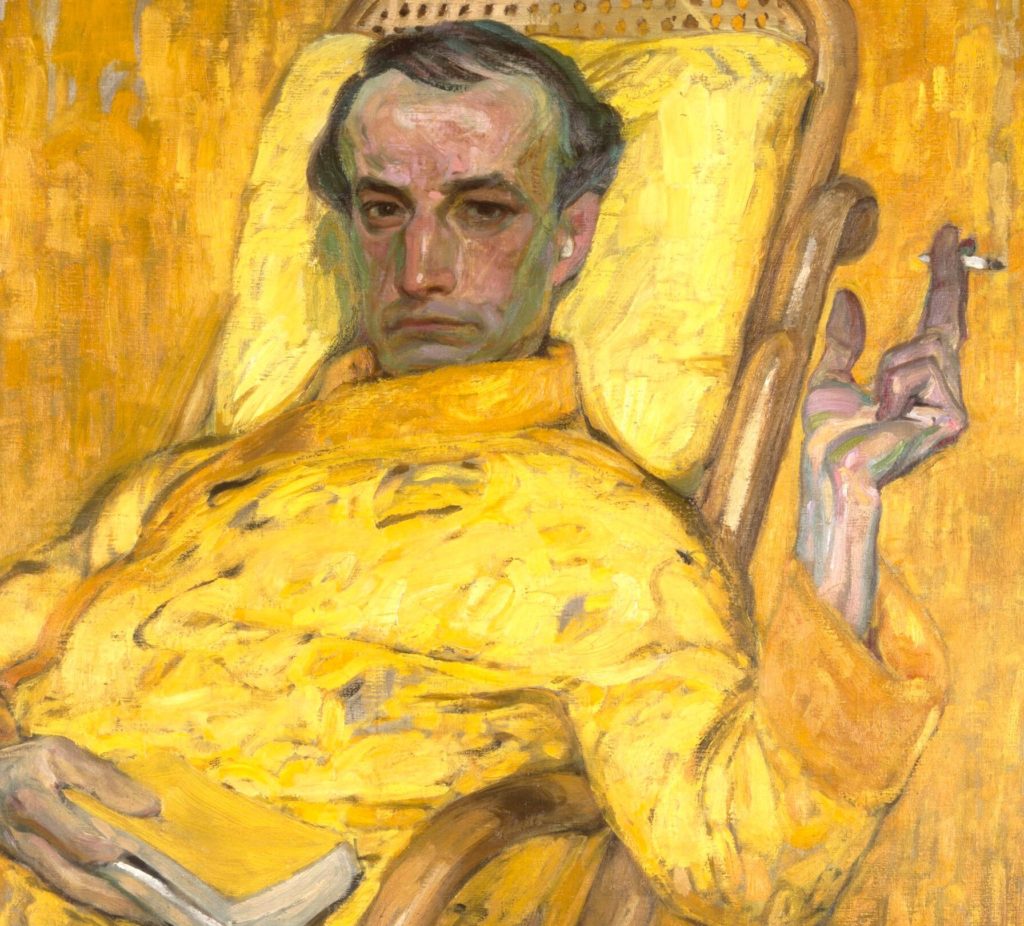

I’m not ashamed to say that I bought Joris-Karl Huysmans’s Against Nature because of the cover: Frantisek Kupka’s The Yellow Scale (Self-Portrait) from 1907 is an exhilarating study of the color yellow. Its human subject, slouched in a wicker armchair, a cigarette dangling from one hand while a single, louche finger marks the page of a book, could be the perfect image of Des Esseintes, the dissolute antihero of Huysmans’s novel. Strictly speaking, the painting is a self-portrait of the habitually mustached Kupka, but it bears more than a passing resemblance to Charles Baudelaire, who haunts almost every page of Against Nature. This novel, about a dyspeptic aesthete who “took pleasure in a life of studious decrepitude,” spends some two hundred pages luxuriating in excess and opulence while the hero cuts himself off from the rest of society.

An old idea that persists about the novel is that it ought to be morally instructive in some way, that it should teach us the correct way to live. Certainly, when Against Nature was published in French in 1884, much of the resultant hand-wringing was because Huysmans’s hero learns nothing new from his misadventures in self-isolation. The problem, according to Émile Zola, was “that Des Esseintes is as mad at the start as he is at the end, that there is no form of progression.” Barbey d’Aurevilly, who, depending on your point of view, was either a minor dandy in the Baudelaire coterie or just a nasty little pornographer, agreed: “Undertaken in despair, the book ends with a despair that is greater than that with which it began.” The reader is informed that in the flower of his youth, Des Esseintes often indulged in the pleasures of the flesh and the card table with his peers, but by the time we meet him in the first chapter, he has already begun dreaming of “a desert hermitage equipped with all the modern conveniences, a snugly heated ark on dry land in which he might take refuge from the incessant deluge of human stupidity.” Page after page, chapter after chapter, Des Esseintes throws more and more money after his ennui and deviant tastes. He flees the crowds of Paris for the country, cuts himself off from outsiders, and attempts to swaddle himself only in objects and experiences that meet his particular aesthetic principles. Decadent literature had its heyday in France in the nineteenth century when the poètes maudits sought to overthrow nature, replacing with it human genius and the pursuit of pleasure, no matter how perverted. But for all Des Esseintes’s extravagance, there is nothing that can stop the rot, there is no escaping his malaise. Eventually, he is ordered back to the city by a pragmatic doctor, where he must abandon his solitary existence and at least try to enjoy the same pleasures as other people. All Des Esseintes can manage, before the doctor strides out the door, is a petulant “But I just don’t enjoy the pleasures other people enjoy!” The novel ends with our hero slumped in a chair.

So, what, if anything, do we stand to learn about self-isolation from an ailing aristocrat at the tail end of the nineteenth century? Des Esseintes is based loosely on Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac, the dandy par excellence who was also the model for Proust’s Baron de Charlus. Proust’s roman-fleuve, and Huysmans’s Against Nature, like so many great novels, are concerned with the twilight of a once-golden age.

The dandy was an important figure in decadent literature, a visible manifestation of a society infected by its own opulence. Things rarely ended well for the dandy, whether fictional or historical: they tended to die in poverty and obscurity, their witticisms forgotten, their fashions surpassed. But for a few blazing decades of the nineteenth century, in fiction and in society, they were the absolute arbiters of taste, and Jean des Esseintes might just have been their high priest.

Curated from the pages of Against Nature, the following is a decadent guide to staying home in style. Quarantine, but make it “fun”-de-siècle.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/386ja1v

Comments

Post a Comment