In her column, Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be.

Here’s a question: Can you name the debut novel, originally published in Britain in September 1965, that became a more or less immediate best seller, and the fans of which included Noël Coward, Daphne du Maurier, John Gielgud, Fay Weldon, David Storey, Margaret Drabble, and Doris Lessing? “A rare pleasure!” said Lessing. “I can’t remember another novel like it, it is so good and so original.” Coward, meanwhile, described it as “fascinating and remarkable,” admiring the author’s “strongly developed streak of genius.” Du Maurier—a writer whose own work is famously mesmerizing—declared it “compulsive reading … Endearing, exasperating, wildly funny, touching and superbly amoral.” Gielgud thought it “full of fascinating characterisation and atmosphere.” Never not in tune with the times, Weldon deemed it “a magical mystery tour of the mind,” Storey “a superb piece of confectionery,” while Drabble described it as “strange and unforgettable … Highly original and oddly haunting.”

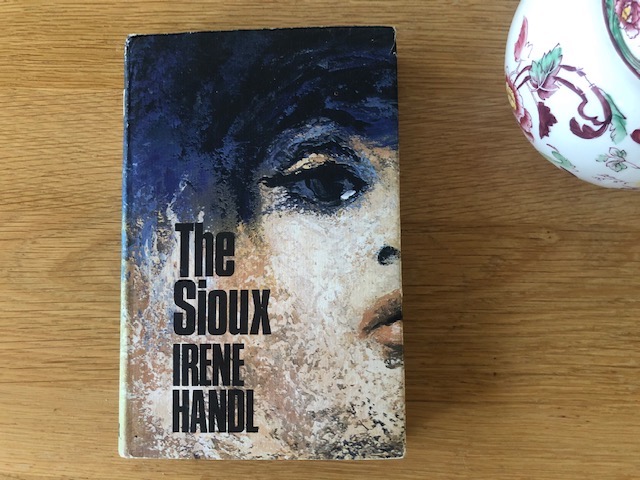

Yet despite such heaped adulation, I’m willing to bet that hardly anyone reading this will have heard of the novel in question, though some might be familiar with its author. It’s called The Sioux, and was the work of sixty-six-year-old Irene Handl, a famous British actress beloved for her roles on both stage and screen, rock ’n’ roll superfan (and member of the Elvis Presley fan club), fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, not to mention a devoted Chihuahua owner and for many years president of the British Chihuahua Club.

The blurb on the British first edition describes the book as “a sustained tour-de-force, one of the most unusual and remarkable novels of recent years.” Unusual and remarkable is spot-on. “The Sioux” is the nickname the Benoir family call themselves, on account of their fierce tribalism. They’re French—their ancestors escaped Paris during the Revolution, fleeing first to Martinique then, during a slave insurrection, from there to Louisiana—feudal, and astronomically rich. Both The Sioux, and its sequel, The Gold Tip Pfitzer (1973)—which is dedicated to Noël Coward—are two of the maddest novels I’ve ever encountered. The Benoirs themselves are among the most appalling and repugnant, monstrously overprivileged, egomaniacal psychopaths ever created. To be absolutely honest, I’m not sure these books should actually be republished—the misplaced cultural appropriation of their chosen soubriquet is, if you can believe it, one of the Benoir family’s least egregious crimes—but, just like Drabble before me, now that I’ve read them, I simply haven’t been able to stop thinking about them.

Even the very existence of these novels is something to be marveled at. Handl apparently first put pen to paper when she was nineteen, while in Paris in the twenties, but abandoned the project after only writing a few pages. It wasn’t until the early sixties, while taking a much-needed break from her stage career due to exhaustion, that she found the time to return to her notebooks and finish working on the story she’d begun all those years earlier. (It was another enforced rest that then afforded her the opportunity to write The Gold Tip Pfitzer.) And what she wrote also defied expectation. Who would have thought that a middle-aged British actress famous for playing working-class stereotypes, from meddling landladies to browbeaten wives, would write a sui generis chef-d’oeuvre of high-camp Southern Gothic? Readers today will recognize an ambiance akin to that found in Patrick deWitt’s “tragedy of manners,” French Exit (2018), or the idiosyncratic style of Wes Anderson’s feature films, though compared to the vicious maneuvering of the Benoirs, the dysfunctional Tenenbaums look as picture-perfect as the Waltons.

These novels aren’t just the feat of an impressive imagination. Handl proves herself an original and flamboyant stylist, oscillating between vaudevillian slapstick, demented dark horror, and passages of sheer—if extravagantly baroque—poetry. Perhaps unsurprisingly for an actor who excelled at character parts, The Sioux is driven by dialogue. And what dialogue it is! A Franglais like no other, sprinkled with private endearments and bon mots, the meaning of which are usually known only to the family, with a dash of “Ol’ Kintuck,” “Creole,” and “Miss’ippa” thrown in for good measure. This is more a novel in speech than anything else, not least because if you strip away all the melodrama and the gaudiness, plot is actually pretty thin on the ground. It takes a while for this lack of story to sink in for a reader though, as the showy voluptuousness of the prose enfolds one in a cloying, claustrophobic embrace. Handl writes in the present tense, sharply shifting back and forth between the interior monologues of her various characters, adding to the muggy intensity of the reading experience.

*

Where to begin ? Well, first things first, with the Benoirs themselves, I suppose, which isn’t at all as easy a task as you might imagine, since each and every one of them goes by a befuddling number of different names (coupled with the fact that, as appears to be an unfortunate side effect of a family that’s as inbred as this one, everyone’s pretty much called some form of the same name to begin with). The novel opens with a transatlantic telephone conversation between the head of the family, Armand-Marie Xavier Benoir (also known as Benoir, Herman, Hermie, and Nap)—who’s at his home in Paris—and his sister, Marguerite (also known as Mimi, Mim, Mi, The Governor of Alcatraz, and Breadcrumb)—who’s at hers in New Orleans, having just arrived back from her honeymoon. Marguerite is only twenty-six but she’s already on her third marriage. Her latest husband is an English banker named Vincent Castleton (most often referred to as Vince, or “Poilu,” on account of his body hair, which apparently distinguishes him from the Benoir men, whose skin is “as smooth as silk”), a likable if often bemused gent who’s clearly bitten off more than he can chew when it comes to the machinations of his dreadful in-laws.

The topic of the siblings’ conversation is Marguerite’s son, nine-year-old Georges-Marie Benoir—also known as Georges, Marie, Little Benoir, Petit-Monsieur, The Dauphin, Puss, Moumou, Old Duck, Little Ducky, Old Dear, Old Man, Old Daddy, Old Darling, Mim’s Chap, His Nibs, King Nutty, Woozy, The Wizard, Mimi’s Flirt, Little Rubbish, Waxy Willie, and Thingo. His father was Marguerite’s first husband, her cousin Georges Benoir, whom she married when she was only sixteen and who perished shortly thereafter in a racing car accident. Armand, incidentally, is also married to his cousin; another Marie Benoir, just to make things even more confusing—here I can’t help but think of Claude Lévi-Strauss’s description of incest as “bad grammar” in the “language of kinship.” The Benoirs’ linguistic acrobatics certainly defy all manner of rules and traditions. That said, a marriage to a first cousin is this family’s idea of expanding their gene pool, especially since there’s more than a whiff of something unnatural about Marguerite and her son’s relationship (in the same way that there was between Armand and his and Marguerite’s mother, while she was still alive). By the time we get to The Gold Tip Pfitzer, the fact that Armand and Marguerite often share a bed is just one of the many shocking discoveries that leaves Castleton reeling.

So, Moumou—who, while his mother and his new stepfather were on their honeymoon, was left in his uncle’s care in Paris—is the heir to the Benoir fortune, but he’s also desperately ill, suffering from acute monocytic leukemia. Not that this is immediately made clear. At first, it’s hard to work out whether we’re dealing with a case of Munchausen Syndrome by proxy, staggering maternal neglect, or just the wild whims of so much wealth and privilege. Marguerite’s beauty is matched only by her cruelty. One minute she’s ordering around servants and relatives alike in the service of the darling Dauphin, instructing them to serve him champagne and oysters in bed or feed him nothing but Vichy water, biscottes, and cognac; the next she’s telling people not to fuss over him. “I don’t spoil him,” she protests. “I love him far too much to let him make a nuisance of himself.” What on earth, wonders poor Castleton—who’s as yet barely met his stepson—has he let himself in for?

Yet, when Marguerite’s son finally arrives in New Orleans in the flesh—deathly pale and very small for his age, the very picture of innocence in his impeccably-tailored snow-white sailor suit—Castleton is surprised to find that the boy is a delight. Sure, he’s a little highly strung, but who wouldn’t be with a family like his? What he absolutely isn’t is the precocious brat that Castleton—and the reader—had been expecting. Incidentally, the boy’s arrival is truly majestic. He and his entourage—his valet, his nurse, his beloved foster sister Dédé (conceived by George’s wet nurse so there would be a ready supply of milk for the little princeling), his personal detective (don’t even ask!), Marguerite’s two French chauffeurs, and Armand, who’s bought with him his two valets as well as his pet capuchin monkey, Ouistiti (who has a penchant for furiously masturbating while perched on his master’s shoulders)—tumble out of two tricolor-flying white Rolls Royces (the second of which is referred to as “The Ambulance” because it’s been fitted out with a bed for the miniature invalid).

Initially, everything looks peachy. How delighted Marguerite must be to have her beloved son by her side once again, even if he does look “spooky as hell and deliciously ready for the mortician”! But at the same time, her mandate for complete obedience doesn’t exactly scream doting mother. Unmoved by the genuine and loving bond forged between her two best boys, she demands that Georges call Castleton “Papa.” The poor little chap is in agony, he can’t bear to disappoint her, nor can he bring himself to call his new friend the name that belongs to his dear dead father only. Given Handl’s confusing emphasis on her characters’ many pet-names, it’s weirdly fitting that one character’s refusal to use a particular moniker should be the fulcrum on which the novel’s plot turns. Castleton himself doesn’t mind what Georges does or doesn’t call him—nor does he understand the fuss his new wife is making—but Marguerite is resolute, so she whips little Moumou into submission, an act of astonishing violence that leaves his tiny, delicate hands a bloody pulp.

The sustained ferocity of the scene is truly shocking—rivaled only by the episode depicting Georges’ death in The Gold Tip Pfitzer, a gruesome, screwball caper as the dying child is chased around a bathroom in the middle of the night, hemorrhaging from a nosebleed of horror movie proportions and eventually dying in Marguerite’s arms, mother and child soaked in blood and mucus. Here, there’s little evidence of maternal love, even twisted. The little boy collapses in pain and despair, while Marguerite’s awful fury escalates with each blow:

He falls to his knees.

She says in a terrible voice: ‘Get up or I will surely kill you.’

She hauls him to his feet, still crying: ‘Jamais, jamais de ma vie,’ and beats him till she can beat him no more.

He shrieks out in a high sweet voice like a terrified bird. ‘Don’t whip me, mama! O, you will kill me with that thing! Pas plus, pas plus, maman-chérie!’

He has slipped down on to the floor, but she has still got hold of his hand. She beats it till she is satisfied. ‘Will you dare to disobey like that again? Will you dare?’

*

Although the scene is undoubtably appalling, it’s not, I’m afraid to say, entirely unexpected. The whip—grimly known as a “soupir d’amour” because the noise it makes “is supposed to resemble the sighs of a young girl in love”—appears, like Chekhov’s gun, in the novel’s second chapter. Small enough to lie “coiled in [a] drawer like a baby snake,” it’s a horrific relic of the family’s ugly past, originally used to “discipline” the slaves on their plantations on the Mississippi delta. This, then, is the Original Sin to which all the amorality, cruelty and vice exhibited by the current Benoirs can be traced back to. It’s sobering enough to understand that the family’s immense wealth is awash with the blood of those they enslaved; but the fact that this remains such a blind spot for everyone involved is especially hard to stomach. The Benoirs aren’t just incapable of self-reflection, it’s much worse than that: they’re all laboring “under the impression they are still living in pre-secession and are happy to spend the rest of their lives up to the eyebrows in Spanish moss.” Georges’ nurse Madeleine—whom Marguerite insists on calling “Mammy”—is, like many of the family’s servants, directly descended from slaves on one of their plantations, for example, and she’s not treated much better than her ancestors were. And Marguerite’s vileness when it comes to Madeleine’s daughter Dédé—whom Georges loves like a sister and likes to sleep beside at night—is quite physically painful to read.

This is an illustration of how the legacies of slavery reverberate through the generations—not simply how long-ingrained systemic inequality is near impossible to escape, even if we like to claim times have changed — but of how the cruelty and violence that white slave owners enacted on their Black slaves with such impunity was then replicated and continued for years to come. But at the same time, if ever there was a book that needed some serious trigger warnings, this is it. Handl certainly deserves recognition as a writer of uncommon talents. These were the only two books she published, though I sorely wish she’d had the time and energies to have produced more, if only to have seen whether she could dream up anything to rival the Benoirs. And yet, no amount admiration can detract from the disturbing horror she portrays.

Castleton’s marriage to Marguerite only lasts fourteen months, but his entanglements with the Sioux leave him feeling “like the sole survivor of a mine disaster.” That is more or less what I felt like myself after turning the final page and resurfacing, shell-shocked and decidedly worse for wear back into the real world (which is saying something given the absolute state of things right now). Reading these books is a visceral experience, an assault on the senses. From her indulgent descriptions of dinner tables overloaded with delicious gourmet delights, to the fragrant enchantments of a courtyard garden in the early evening—“where all the brilliant flowers have been freshly sprayed for the night, the callas and the cannas and the belles de nuit, and the begonias and the bignonias and the Cherokee roses, and where the fountain is splashing away like fun among the palmetto fans”—it all builds to a near-suffocating crescendo, one that ultimately left me slightly nauseated and gasping for breath. “I dislike people that think a terrible lot of money,” Handl said, when asked about the origins of her grotesque fictional creations. “Except they’re very funny, and I write about them nastily.” No one could try and claim that Handl expresses any sympathy with her characters; the only problem here is that sometimes their nastiness outweighs hers.

Read earlier installments of Re-Covered here.

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, the Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review, and LitHub, among other publications.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3adDJZF

Comments

Post a Comment