We didn’t drive in over the bridge. That was one surprise. I remember thinking we’d see the Transamerica Pyramid piercing the fog, or the bay sparkling in the distance. Instead, when I first visited San Francisco in the eighties, we arrived by tunnel. The BART train from Berkeley spat us out into the noisy, echoing heart of downtown. This was 1984, the city in near collapse, AIDS a full-blown crisis—the Reagan administration mocking its sufferers. As my family trudged up Kearny Street, we were stopped every few paces. Men whose clothes were in tatters asked us for money, food, anything. You’ll still encounter destitution in the city today; tech wealth merely rivers around it. To my child’s eye, it seemed apocalyptic then. How could a city pretend it wasn’t collapsing?

By midday we stumbled into a bookstore. Perched on the corner of Columbus and Broadway, City Lights emerged like an oasis. Stepping into the shop, I recall thinking it had a very different idea of what we all needed to drink. Books about revolution, the theft of the North American continent, and community action sprawled over several levels. Poetry had an entire floor. I may have been ten, but my parents were radicals; I could recognize the tribal markings of left-wing thought. Everywhere you looked, there were the city’s problems, written about in books. On placards. Broadside poems. Slogans sketched right onto the shop walls. The store was promising an escape by showing you how to escape back into social engagement: I’d never been anywhere like it.

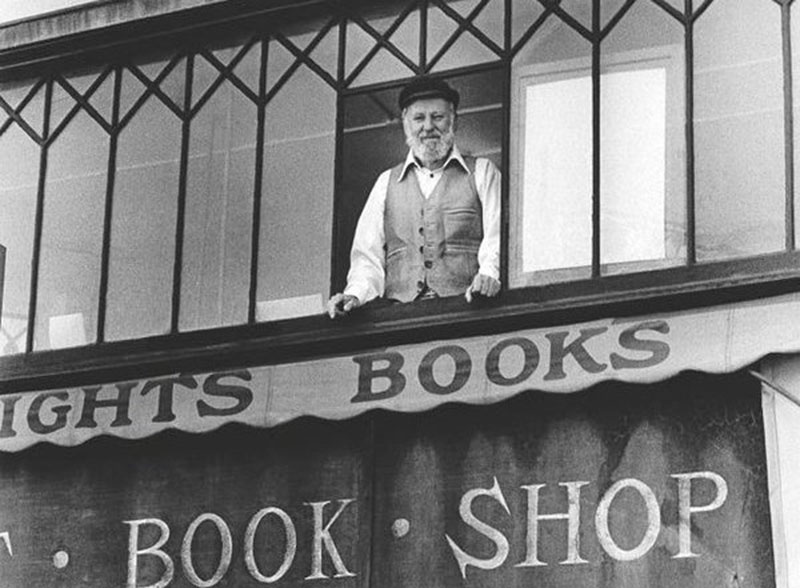

That was thirty-seven years ago. Now, in the middle of the pandemic, the store is still open and it’s thriving. But yesterday it said goodbye to its eternally hip hundred-and-one-year-old cofounder, the poet, publisher, and community activist Lawrence Ferlinghetti. No one in American letters ever pushed back against power over such a long time as Ferlinghetti. He fought power as a poet, as a bookseller, and as a publisher. His poems in Coney Island of the Mind woke up a generation to the nightmare of the military industrial complex in America. In City Lights, the first all-paperback bookstore in the country, readers found fellow travelers for cheap prices. From City Lights Books, which has published everything from Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” to Rebecca Solnit’s first book to a recent title on drone strikes, the question of moral values in the age of empire has been explored more deeply than anywhere else in American publishing.

It’s an aging history to some degree, judging by Ferlinghetti’s hundredth birthday celebration nearly two years ago. For the longest time, City Lights was a young person’s holy site. On that Sunday afternoon in 2019, though, the store was crammed with people in their fifties, sixties, seventies, and older. Many men wore hats—bowlers, watch caps, fedoras, berets, even cowboy hats. Almost no one was under thirty. Following a rousing opening address from Elaine Katzenberg, the store’s director, the day began with a reading of a Ferlinghetti poem by eighty-six-year-old Michael McClure, one of the five poets who’d been on the bill for the famous Six Gallery reading in 1955, which scholars often pinpoint as the start of the Beat Movement. The other four were Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Philip Lamantia, and Philip Whalen. Ferlinghetti published all of them in the store’s Pocket Poet Series. Jack Hirschman, eighty-five-year-old former San Francisco poet laureate, followed by reading Ferlinghetti’s great poem, “The Sea,” in “which he gives death a kick in the ass at age 90.” Hirschman’s voice was the sound of the Ancient Mariner.

Over the next six hours, North Beach—the still-scuzzy neighborhood of strip clubs and Italian eateries that City Lights barnacled itself onto—hosted a day-long celebration. I wandered into Cafe Zoetrope down the street from the store and listened to one of America’s most exciting young poets, Sam Sax, reading Ferlinghetti’s poem “Dog,” which follows an animal across the city, “looking/like a living questionmark/into the great gramaphone/of puzzling existence/with its wondrous hollow horn.” A group of actors performed one of Ferlinghetti’s interventionist plays from the seventies in Jack Kerouac Alley. Former U.S. poet laureate and longtime Berkeley resident Robert Hass talked about the way that having Ferlinghetti in the Bay was like having a benevolent sun forever shining, making clear sight possible. Ishmael Reed showed up, and Paul Beatty, too, although he was just watching. As the day warmed, more young people appeared and the store became what it always is—a many-ventricled heart, pumping out light and ideas.

Ferlinghetti wasn’t around. The store’s staff sang him happy birthday shortly after dawn, serenading him in his North Beach apartment from the street. He came to the window, natty as ever, wearing a red scarf, and waved. For a person at the center of things, he was always a little off to the side, eschewing the light—he preferred instead to reflect it. You see this in the work. Ferlinghetti’s Greatest Poems, published several years ago by New Directions, covers an astonishing sixty years of production, and no matter where you dip into it, there’s a cascading movement across and through the day’s darkest events—Vietnam, the eco-cidal creep of climate change—back into lightness. Like Walt Whitman, Ferlinghetti writes a long, prosey poetic line, but his I is softer, stranger, and less verbose. His lineation steps across the pages with sudden, perfectly timed enjambments that allow for swerves toward tenderness, wonder, and mourning.

The magic of Ferlinghetti’s writing exists entirely in those transitions. They allow for his politics never to become the hinge upon which the door of a poem swings, but rather something larger and more eternally humane, even, hopeful. In “Two Scavengers in a Truck, Two Beautiful People in a Mercedes,” the poem smashes together two opposite social classes at a red light and, briefly, finds a chink of optimism in that sudden juxtaposition, “all four close together / as if anything at all were possible / between them / across the at small gulf / in the high seas / of this democracy.” In America, the long fallout of Modernism and confessional poetry has made someone like Ferlinghetti hard to place. Unlike T. S. Eliot, whose “Wasteland” he revered, Ferlinghetti was deeply allergic to the idea of art for art’s sake. And, unlike the confessionalists, such as Sylvia Plath and Robert Lowell, he was skeptical of the self and ego and mythologizing.

The key to how Ferlinghetti found a line between these poles lies in his time in France. It was to France he went on the GI Bill for a graduate degree at the Sorbonne, and where he read in great depth the surrealists, like André Breton and Antonin Artaud, both of whom he’d publish. He also read Jacques Prévert, whose “Paroles” was published in 1948, and which Ferlinghetti translated for the first time into English and published in the Pocket Poet Series. Prévert’s playful realism, his rhythmic repetition of lines, such as in “Sunday” (“Remember Barbara”), and his bent conception of the real are all also hallmarks of Ferlinghetti’s work.

Asked recently by Dwight Garner of the New York Times about the Beats, Ferlinghetti named their only committed surrealist, William S. Burroughs, as the best writer of that generation. Ferlinghetti’s affinity to Burroughs wasn’t just artistic—it was generational. The two of them were born a decade before Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Snyder. Born Lawrence Ferling in Yonkers, New York, in 1919, Ferlinghetti had been sent off to France as an infant. His father had died and his mother had been committed to what was then called an insane asylum. (He later restored his original family name.) Ferlinghetti didn’t learn English until he returned to America at age five with his aunt. She raised him in a suburb of New York City, where she worked on an estate as a governess. She later abandoned him, and he stayed with other family members until the stock market crash of 1929, when he was taken in by yet another family, who sent him to boarding school after he was caught stealing.

Though technically an orphan twice over, he somehow wound up with degrees from the University of North Carolina, Columbia University, and the Sorbonne, when the cultural capital of the world was shifting from France to the U.S. His patriotism had carried him away from America: in World War II, he captained a submarine on D-Day, but when he saw what the Atomic bomb had done, he instantly became a Pacifist. He stayed away so long he began, like so many expats, to identify with elsewhere. “When I arrived in San Francisco, I was still wearing my French beret,” Ferlinghetti once told me, laughing, in an interview. “The Beats hadn’t arrived yet. I was seven years older than Ginsberg and Kerouac, all of them except Burroughs. And I became associated with the Beats by later publishing them.”

Through the long lens of history, it seems likely Ferlinghetti’s legacy as a publisher will stand as much on the beats as on the younger writers he published. In the last sixty years, a cavalcade of black Marxists (Bob Kaufman), Latin American poets of resistance (Daisy Zamora, Ernesto Cardenale), stylish young short story writers and novelists (Rebecca Brown, Rikki Ducornet), and left wing thinkers have emerged from the presses on Columbus Avenue. For many readers, the pocket poet series was their first introduction to Frank O’Hara (Lunch Poems) and Denise Levertov (Here and Now), let alone the great Bosnian poet, Semezdin Mehmedinović (Nine Alexandrias). To this day, you can find all these titles in the store.

Ferlinghetti wound up a bookseller by accident almost. A friend, Peter Martin, had been publishing a literary journal called City Lights, after the Charlie Chaplin film, and needed revenue to keep the magazine afloat. Martin suggested opening a bookstore, an idea Ferlinghetti loved because he had just returned from Paris where books were sold from stalls along the Seine as if they were loaves of bread. It turned out to be a savvy business decision. City Lights opened at the height of the paperback book revolution, in a city crawling with avid readers.

“We were filling a big need,” Ferlinghetti once told The New York Times Book Review:

City Lights became about the only place around where you could go in, sit down and read books without being pestered to buy something. That’s one of the things it was supposed to be. Also, I had this idea that a bookstore should be a center of intellectual activity, and I knew it was a natural for a publishing company, too.

While some of the Beats drank their talent away, Ferlinghetti worked diligently on his own poems. The jazzy, scabrous rhythms of Coney Island of the Mind were a call to arms for resistance in an era of unchecked American power:

I am waiting for my number to be called

and I am waiting/for the living end

I am waiting/for dad to come home

his pockets full of irradiated silver dollars

and I am waiting/for the atomic tests to end.

This message eventually reached more than a million readers, making “Coney Island of the Mind” one of the best-selling poetry volumes of the 20th century. The book trailed him like a friendly ghost. It also bought him the space to continue experimenting. In the 1960s alone he published his first novel (Her), an environmental manifesto, a broadside about Vietnam, a book of a dozen plays, and his own Whitmanesque third collection “Starting Out from San Francisco,” which landed in advance of the hippy movement with a kind of warning that with liberation-lite comes responsibility. “As I approach the state of pure euphoria/I find I need a large size typewriter case/to carry my underwear in and scars on my conscience.”

One of Ferlinghetti’s great gifts was his ability to be a public and private poet at once. In the 1960s and 1970s, his poems appeared in The San Francisco Examiner, sometimes on the front page, as they did when Harvey Milk was assassinated. For decades you could find him in Cafe Trieste, writing, as Francis Ford Coppola later did. He traveled widely, as 2015’s “Writing Across Landscape: Travel Journals,” made clear, with its dispatches from Spain, Latin America, Haiti, Cuba — where he witnessed Castro’s revolution — and Tibet. But Ferlinghetti always came back to North Beach. His lovely poem from the 1970s, “Recipe for Happiness in Khabarovsk,” is a kind of melding of the cosmopolitan world and the one you’ll find today still inside Cafe Trieste, no matter how many tourists turn up.

One grand boulevard with trees

with one grand cafe in the sun

with strong black coffee in very small cupsOne not necessarily very beautiful

man or woman who loves youOne fine day

On the day of Ferlinghetti’s 100th birthday last year, the March sky was an uncharacteristically bright un-San Francisco blue. As the sun dipped below the horizon, and the aging beatniks drove back to Marin, I left some friends at a bar and walked up past City Lights, expecting to find it a wreck, or at least showing the tell-tale signs of dissipation. Instead, the rolling bookcases had been pushed back into place, the interior lights were illuminated, people were browsing. Here was the missing thirty-and-under crowd. They were moving about in the light Ferlinghetti kept lit in the bay, so that others could see the wreck we’d made of the world — and also, hopefully, the way to repair it.

John Freeman is the editor of Freeman’s and author of The Park, a collection of poems.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2OZNwLW

Comments

Post a Comment