In her column, Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be.

Like many readers, I suspect, I first came across the name Mohammed Mrabet in relation to Paul Bowles. Throughout the 1960s, 70s and 80s, everyone from Life Magazine to Rolling Stone sent writers and photographers to Tangier—where Bowles had been living since 1947—to interview the famous American expat, author of the cult classic, The Sheltering Sky (1949). “If Paul Bowles, now seventy-four, were Japanese, he would probably be designated a Living National Treasure; if he were French, he would no doubt be besieged by television crews from the literary talk show Apostrophes,” wrote Jay McInerney in one such piece for Vanity Fair in 1985. “Given that he is American, we might expect him to be a part of the university curriculum, but his name rarely appears in a course syllabus. Perhaps because he is not representative of a particular period or school of writing, he remains something of a trade secret among writers.” This wasn’t to say that Bowles was reclusive though. In fact, he kept open house for one and all, whether they be curious tourists, his famous friends—Tennessee Williams, William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg amongst them—or the crowd of Moroccan storytellers and artists he’d befriended over the years. And of these, one man in particular stands out: Mohammed Mrabet.

Bowles and Mrabet met in the early 60s, and they remained close until Bowles’ death, four decades later, in 1999. Mrabet worked for Bowles in various capacities; as a driver, a cook, general handyman and sometime travelling companion. But theirs was much more intimate a relationship than that of employer and employee. They were friends—and it’s assumed, at one time or other, lovers too—but most importantly, artistic collaborators. Throughout the 1960s, Bowles increasingly turned his attention to translating. His wife, the novelist Jane Bowles, suffered a stroke in 1957, from which she never fully recovered. From then until her death in 1973, she was plagued by depression, impaired vision, seizures and aphasia; health problems that also had a notable impact on her husband, depriving him of the “solitude and privacy” that he needed to write. “The real reason I started translating, was that Mrs. Bowles was ill and I couldn’t write, because I would only have twenty minutes and then I would be called downstairs,” he explained to McInerney.

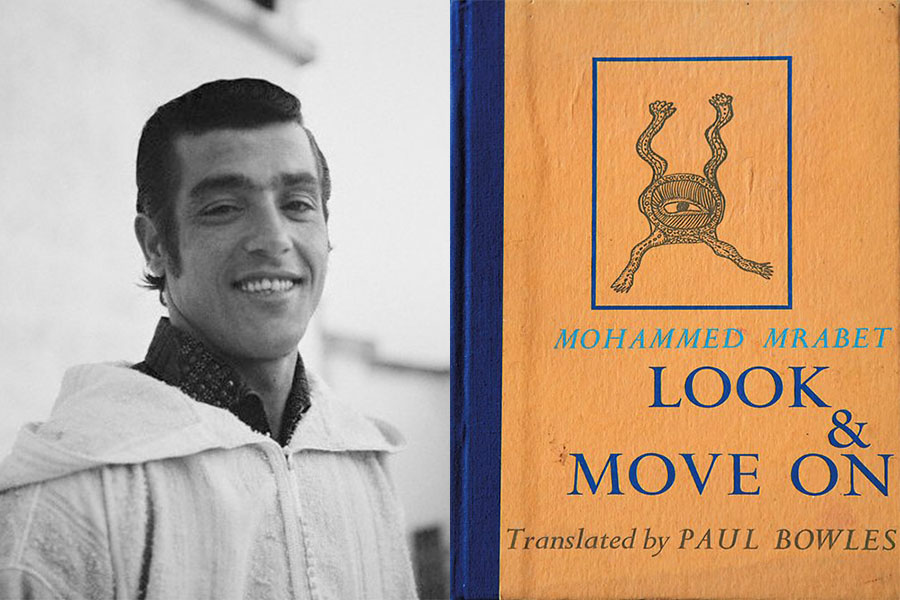

But what started out as a piecemeal activity that could be squeezed in between the demands of caring for his spouse soon became an impressive project in and of its own right. Bowles worked with oral storytellers who hadn’t learnt to read and write, Mrabet included. Thus, in taping, transcribing and translating their tales, he was, as McInerney points out, “virtually inventing a new genre.” He also developed close bonds with many of the men he worked with. Take, for example, the writer, playwright and painter Ahmed Yacoubi, who was Bowles’ protégé (and most likely also his lover) until he emigrated to New York in 1966. But his collaboration with Mrabet was by far the longest of these relationships. The first project they worked on together was the novel-length Love with a Few Hairs (1967)—the story of a young man who pays a witch to cast a spell over the girl he loves so she will agree to marry him, and which The New York Times declared “an engaging and readable story, often touching in its account of a Moroccan youth still in the grip of old tenets and customs while struggling with the new”—and the last was Chocolate Creams and Dollars (1992). In between they coproduced another eleven volumes, mostly stories, but also Mrabet’s memoir, Look and Move On (1976).

As entertaining as Mrabet’s stories are, they inevitably lack a certain polish. For all Love with a Few Hairs’ charms, The New York Times argued that Mrabet would have done well to explore more perspectives than that of his central character. Meanwhile, although Mrabet’s talents as a raconteur are noted by one and all—McInerney, for example, calls him a “born performer”—this isn’t something that necessarily translates onto the page. As such, it’s easy to understand how his stories have fallen out-of-print over the years.

His memoir, however, is a different beast. It’s no masterpiece, but it is a fascinating literary curio. Mrabet’s no-nonsense attitude and unadorned style makes for comfortable reading, and—if, indeed, any further evidence of this is needed—here it’s clear that he’s a man who knows how to tell a good story. As he pinballs from one escapade to the next, freewheeling between moments of comedy and tragedy, Mrabet’s life reads like the adventures of a picaresque hero of old. It’s not that he’s at the mercy of those around him—he’s happy to assert his own agency when he needs to—but more often than not, he’s content to sit back and see where fate takes him. The book offers an intriguing counterpoint to the accounts written during this era by Bowles et al, Westerners who flocked to Tangier because of its louche, exotic and International atmosphere. To see this world through Mrabet’s eyes—as well as his take on Americas and America—is to see it anew.

*

When he’s interviewed by Michael Rogers for Rolling Stone in 1974, Bowles explains that once Mrabet tells a story, “it gets lost.” If, the morning after Mrabet’s been entertaining people with his tales, Bowles then asks him to re-tell one of them so as to record it, Mrabet inevitably professes to have already forgotten the details, and tells a new story instead. So, Rogers asks, he just makes them up on the spot? Bowles explains that he’s not sure whether it’s this, or whether Mrabet “synthesizes them.” He thinks not even Mrabet himself quite understands the process involved, explaining that, since “Moroccans don’t make much distinction between objective truth and what we’d call fantasy,” the whole notion of making something up in the way Westerners understand it might simply not be relevant. When, in Look and Move On, Mrabet describes the stories he tells to Bowles, he credits a wide array of inspiration: “Some were tales I had heard in the cafés, some were dreams, some were inventions I made as I was recording, and some were about things that had actually happened to me.”

When it comes to his memoir though, Mrabet had little need to embellish; his life was so full of incident, it was a story begging to be told. Much of what he writes about concerns the years before he met the Bowles (it’s actually Jane whom he meets first, and then she introduces him to Paul). They appear relatively late on in the book, and they’re certainly not the most enigmatic Americans featured in its pages. That privilege is reserved for another couple, known here as Maria and Reeves, whom Mrabet meets when he’s only 16, and working as a caddy at the golf course at Boubana, just outside Tangier, in the early 1950s. The teenage Mrabet is already a singular figure; he’s unworldly in that he’s had little in the way of memorable experiences—he didn’t finish school, nor is he trained for a particular profession, and he spends much of his time drinking to excess and smoking copious amounts of kif. But he’s not at all naïve, and he immediately gets the measure of these two American predators.

Mrabet and the couple get to chatting in a café, and in a matter of hours they’ve taken him back to their apartment. “It was at that moment I said to myself: Both these people are vicious,” Mrabet recalls. “They both want to sleep with me.” Not that he minds being taken advantage of. He’s drunk, high and attracted to both, so he makes love first with Reeves, and then Maria. If anything, it’s the couple who don’t know what they’ve let themselves in for. They come barrelling into Mrabet’s life with a serious white saviour complex. “As soon as we saw you, the first time, we both thought the same thing in the same moment, that we were going to do something to try and save you from the terrible life you’re living,” Maria tells him condescending. “We felt we had to help you somehow. We don’t want to see you hungry, or sleeping in terrible places. It hurts us to think of you suffering like this.” Mrabet, however, is quick to correct them: “Excuse me, I said to Maria, I want to say something. I’ve never gone hungry. I come from a big family, and we don’t need friends to help us. The life you see me living is the life I picked out for myself, the kind I wanted. I’m not a boy. I know the difference between what’s good and what isn’t. It’s very kind of you to worry about me and want to help me. I appreciate it. But it’s impossible.” All the same, he lets himself become embroiled in a tense ménage à trois, one that sees husband and wife bickering over whose turn it is to have him in their bed that night.

As with everything he relates, Mrabet doesn’t provide much context outside his own immediate experience, but we are able to infer that this sort of sex tourism is abundant in Morocco at this time. When Maria rather foolishly professes that she and Reeves want to treat him like a son, Mrabet is having none of it. “Half the Europeans who live here in Tangier like to live with young Moroccans,” he tells her frankly. “When the old English ladies go back to London they leave their boy-friends behind, and you see the boys wandering around the streets looking like ghosts. They have money in their pockets, but their health is gone. And it doesn’t come back.” He’s wise beyond his years when it comes to the predilections of his paramours.

Mrabet is, however, eager to see the world. When Maria and Reeves invite Mrabet to sail back to New York with them, he agrees. His family are worried, believing America is a “very dangerous country, full of savages killing each other,” but Mrabet doesn’t let these fears deter his search for adventure. But for Mrabet, as for many who’ve made the same journey both before and after him, the American Dream fails to deliver. One of the things he notices immediately is the glaring racism. He’s an astute observer of the uncomfortable reality behind the polite façade. He’s only been in New York for two days when he asks Maria why the white people don’t like the Blacks. “Mostly it’s because they’re dangerous to society,” she tells him. “You mean society’s dangerous for them,” Mrabet corrects her. He understands immediately how American society works:

The white people think they’re better because they have white skin. It’s really the opposite. The only dark thing about a black man is his skin, but the white man’s heart is black. And yet they’re both the same race. The big difference is that the black man is poor. And the white man wants him poor, so that he’ll do the work the white man doesn’t want to do himself.

Mrabet’s sojourn in America is full of such moments of clarity, namely because he refuses to play by the rules of so-called civil society. And nowhere is this more apparent that when he travels to Iowa to visit Reeves’ family. Reeves’ parents are horrified by their hard-drinking, chain-smoking houseguest. Reeves’ father insists Mrabet cuts his long hair, going as far as to give him a buzz cut himself. When Mrabet kills and cooks robins he catches himself in the family’s garden, everyone is horrified by what they regard as his savagery. Yet rather than allowing himself to be shamed for his behaviour, Mrabet is adamant that he’s done nothing wrong.

The book is peppered with occasional moments of searing acuity, but most of the time, Mrabet shows no interest in analysing or picking apart either the decisions he has made, nor displays much empathy to those closest to him. Due to the almost slapdash way in which Mrabet offers us his keen insights, the true extent of his powers of perception are easily underestimated.

*

Mrabet is still alive today—he’s eighty-four years old—thus Look and Move On only tells a fraction of his life story. He has survived Bowles and all those other American and British writers and artists who found both inspiration and sexual freedom in Morocco during a time when their own countries were much less forgiving. According to Jeff Koehler, who travelled to Tangier to interview Mrabet in 2019, he’s still telling stories. These days, he also paints, though his attitude towards that medium is similar to his attitude toward storytelling, in that he’s never been much interested in critical acclaim—“His literary success is a source of some amusement to Mrabet,” Rogers reported, when he met the Moroccan back in the early 70s, “who does not, himself, think too much of writers, intellectuals and kindred occupations,” and as for his paintings, “He won’t explain their narrative or help decode the symbolism that is so obviously present, or even give the works names,” reports Koehler. “Questions are met with a disinterested shrug.” Indeed, if one pushes Mrabet into identifying his profession, he apparently claims he’s neither a writer nor a painter, but rather a simple fisherman.

One sees the same refusal to conform in Look and Move On. Not only does Mrabet treat his work with Bowles, and the subsequent publication of his first book—by the extremely well-regarded British publisher Peter Owen—as an incident of no more or less import than anything that was happening in his life at that time: becoming Bowles driver, for example; or the nefarious means by which he steals another man’s bride’s virginity. But neither does Mrabet show any interest in celebrity. The book is littered with mentions of famous people, from Bill Burroughs—the “tall American they call El Hombre Invisible”—the Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton and her seventh husband Prince Champassak (a title that she’d purchased for the man formally known as Raymond Doan), to Tennessee Williams, whom Mrabet meets when he travels to California with Paul. (His second trip to America leaves him just as disappointed as the first; he’s especially unimpressed by Los Angeles, which he finds “like the Sahara, only dirty.”) But he’s not name-dropping in the way we might expect. As both a writer and a man, Mrabet continually defies expectations, something that makes Look and Move On a curious book, and an important artefact amongst so many others of its time, one that made some notable headway in articulating a non-western perspective.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/37Rjl01

Comments

Post a Comment