Jimbo in Despair, the drawing used as a color overlay on pages 86–87 of Gary Panter’s Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise.

The first time I drew Jimbo … I knew I’d always be drawing him. I don’t know why.

—Gary Panter

Jimbo was born in 1974, two years before Gary Panter moved from Texas to Los Angeles. He is a combination, Panter says, of his younger brother; his friend Jay Cotton; the comic-book boxing champ Joe Palooka; Dennis the Menace; and Magnus, the titular tunic-clad robot fighter in Russ Manning’s mid-century comic; as well as being influenced by Panter’s Native American heritage (his grandmother was Choctaw). Panter has called Jimbo his alter ego, and the character’s most common epithet is “punk Everyman.”

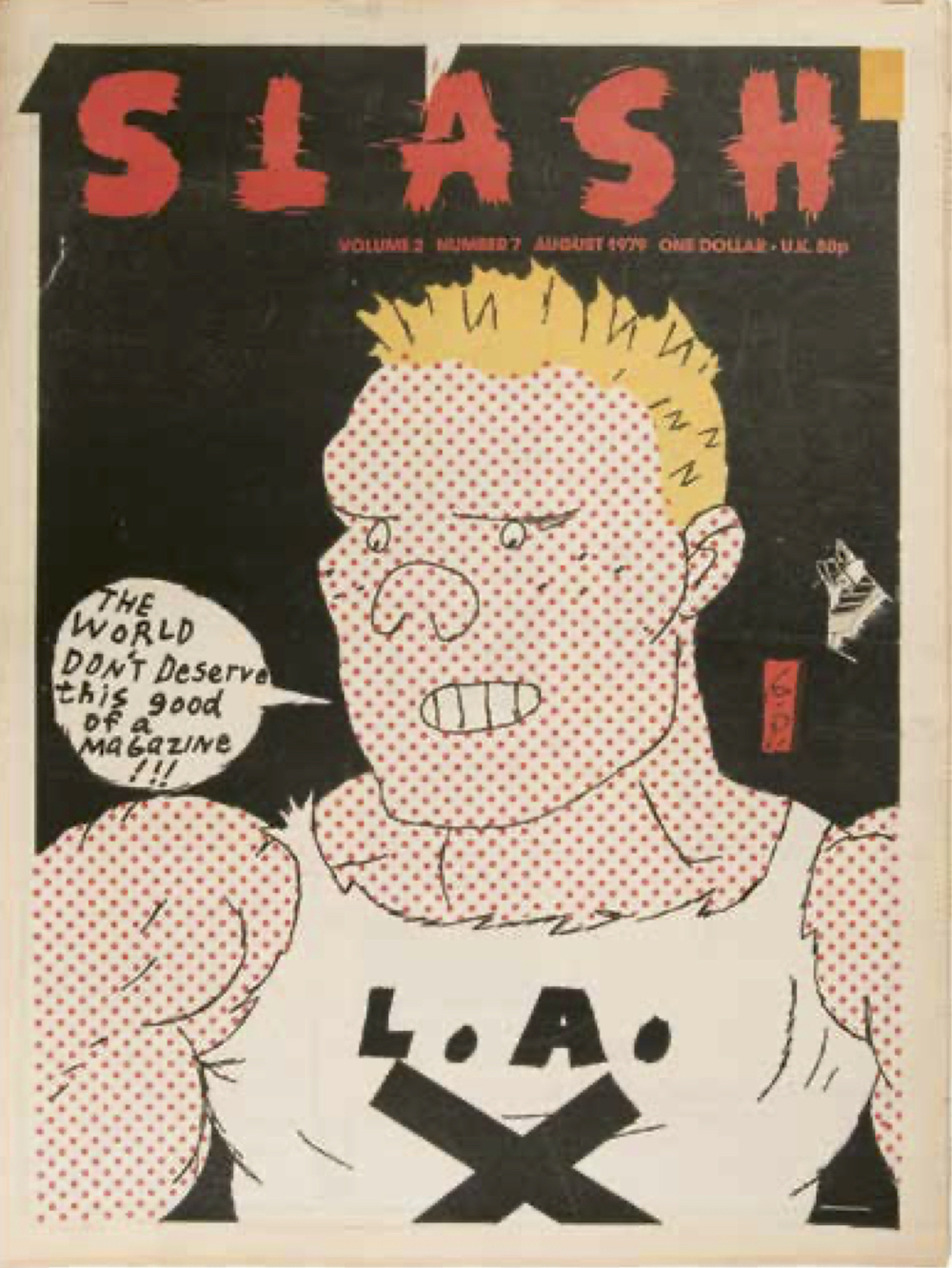

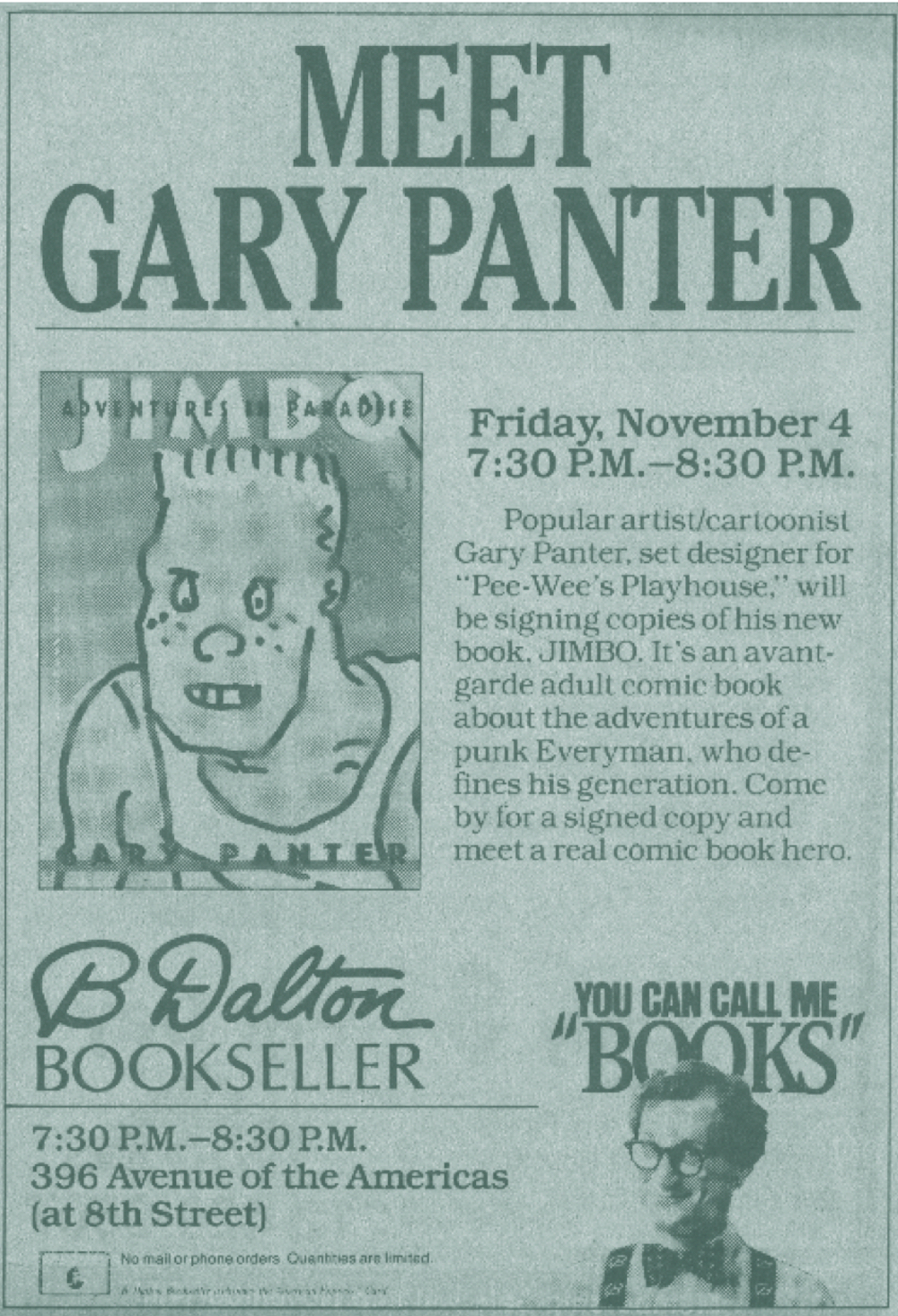

According to Panter, he didn’t set out to create Jimbo, “he just showed up.” Jimbo made his first public appearance in the punk magazine Slash in 1977 and his cover debut two years later. His pug-nosed mug moved to Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman’s radical art-comics anthology Raw in 1981; some of Jimbo’s stories there made up the first Raw One-Shot, a spin-off of the periodical, the following year. He joined an ensemble cast in Panter’s Cola Madnes, written in 1983 but not published until 2000, and landed his first full-length book, Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise, in 1988, published by Raw and Pantheon. Jimbo has since starred in four issues of a self-titled comic published by Zongo in the nineties and stood in for Dante in two illuminated-manuscripts-cum-comic-books: Jimbo in Purgatory (2004) and Jimbo’s Inferno (2006). He is, as you read these words, being sent out into fresh adventures by Panter’s fervid imagination and tireless pen.

Gary Brad Panter was born in Durant, Oklahoma, in 1950 (in his birth announcement, the local paper presciently misspelled his middle name as “Bard”). His family moved to Brownsville, Texas, in 1954, and then to Sulphur Springs four years later, where Panter would remain until he left for college, twenty miles away in Commerce, in 1969. In Brownsville, the family house sat across the street from a drive-in movie theater, and the glowing screen was visible from the front yard. He saw Fantasia there, and The Animal World, a 1956 documentary with an extended stop-motion animation sequence of dinosaurs fighting created by Ray Harryhausen and Willis O’Brien. At the theater in town, Panter saw his first monster movie, The Land Unknown (on a double bill with The Curse of Frankenstein, both 1957), about an expeditionary party that accidentally lands in a prehistoric jungle in Antarctica. He still recalls the primitive special effects: actors in monster suits and monitor lizards standing in for live dinosaurs. Panter’s father, an amateur painter of Western pictures, ran two dime stores, wonderlands of dinosaur figurines, toys, and comic books like Donald Duck, Mighty Mouse, and Turok, Son of Stone.

Set against the capacious Texas landscape, these first encounters with visual culture—both the shabby otherworldliness on the screen and the proliferating pop detritus of the dime store—form the bedrock of Panter’s art. It is overlaid with the Church of Christ teachings of his youth and his later break with religion, and his first encounter, almost mystical in Panter’s telling, with hippie culture:

It was the summer of 1968. We decided to drive our old station wagon from Sulphur Springs to Mount Shasta, California, to visit our cousins … [My cousin] Hotrod was in high school and he drove me around town … He drove us by where the hippies lived in town in a ranch-style home with the yard grown up three feet high and a car up on blocks in the side yard.

The [head] shop was dark and smelled like BO, incense, patchouli. Cloth was draped over tables, and the counters were draped or had stickers on the wood. There were flyers in the window. The place was small. There wasn’t a lot of merchandise. No bongs or manufactured stuff. A girl dressed like a hippie was silkscreening a version of the famous Mindbenders poster [by Wes Wilson]. And there were flutes, leatherwork, stone pipes, a hookah, ceramics, beadwork, beads in vials for sale. And a little loom. God’s eyes of yarn. Maybe four people in there being hippies. Psychedelic posters, essences, underground newspapers … It was what a hippie shack should be like. It was alien like Satyricon is alien.

At art school at East Texas State University, Panter was introduced by his professor Bruce Tibbetts to the writings of Marshall McLuhan and Burroughs, to John Cage’s Silence and Stravinsky’s notes on composition, and to the music of Frank Zappa. Robert Smithson visited the school and screened his film Spiral Jetty (1970), a portrait of the earthwork that the artist imagined transcending time and linking the earthly and celestial spheres. Panter consumed art and culture widely and freely, and the collision of disparate elements produced Dal Tokyo around 1972, a futuristic Martian city in which many of Panter’s comics are set. The name blends Dallas and Tokyo, reflecting not only the here and the elsewhere for an East Texas art-school kid but also the origin of the invented land itself: a city terraformed by Texan and Japanese workers and populated by a multitude of aliens. The influences on the creation of Dal Tokyo are legion: J. G. Ballard, Philip K. Dick, Burroughs, and Anthony Burgess; Charles Fort, Immanuel Velikovsky, and books on UFOs; Alice in Wonderland and Oz; Donald Barthelme and Gravity’s Rainbow; cowboy, monster, and Hercules movies; slot racing and Marx-brand play sets (Civil War, spacemen, Romans); modern art, hippie art, and the Sears Christmas catalog. As a “cultural and temporal collision,” according to Panter, it seems to take as a directive Smithson’s desire for “a map that would show the prehistoric world as coextensive with the world I lived in.” It is a world of near-limitless storytelling possibilities, a cultural fusion so complete that it engenders an utterly new world altogether, capacious and flexible enough to meet the unique demands of each Panter comic.

Punk hadn’t infiltrated Texas, as far as Panter knew, but his artistic efforts—in particular the Devo-esque art group Apeweek that sought to invade and pervert the media—predicted the improvisatory and rebellious spirit he’d find in the punk atmosphere in LA. Apeweek, comprising Panter and art-school friends (and later Pee-wee’s Playhouse collaborators) Jay Cotton and Ric Heitzman, made puppet shows, videos for Dallas public television, art installations, and performances in 1974 and 1975. Its imperative was “art that you could make out of a Gibson’s Discount store and use it all wrong,” Panter says. The group’s provocations paralleled those of the contemporaneous Ann Arbor art noise collective Destroy All Monsters, and helped spawn the Church of the SubGenius in North Texas, a legendary huckster cult formed in 1978 that used the language of evangelism—religious and commercial—to wage an outrageous and absurd fight against the “conspiracy of normalcy.”

Panter carried this disruptive, vernacular approach with him to LA in 1976, where he discovered a forward-looking, if not strictly punk, atmosphere. Though he found that “nobody was taking Dubuffet, Jack Kirby, and David Hockney and putting them together with Peter Saul, the Hairy Who, and Fahlstrom,” as he was, he did locate disparate models and like minds for his burgeoning brand of formal hybridization and cultural synthesis. He looked up the illustrators Cal Schenkel and Jan Van Hamersveld and visited Kirby at his house in Thousand Oaks. He became friends with Ed and Paul Ruscha after he knocked on the door of Ed’s studio on Western Avenue. He met Mike Kelley through Claude Bessy (a.k.a. Kickboy Face), an editor of Slash. Leonard Koren liked his portfolio and let him advise on an issue of Wet, the graphically adventurous magazine of “gourmet bathing” that launched in 1976. Koren later introduced him to a young cartoonist named Matt Groening, whose strip Life in Hell made its debut in Wet in 1978.

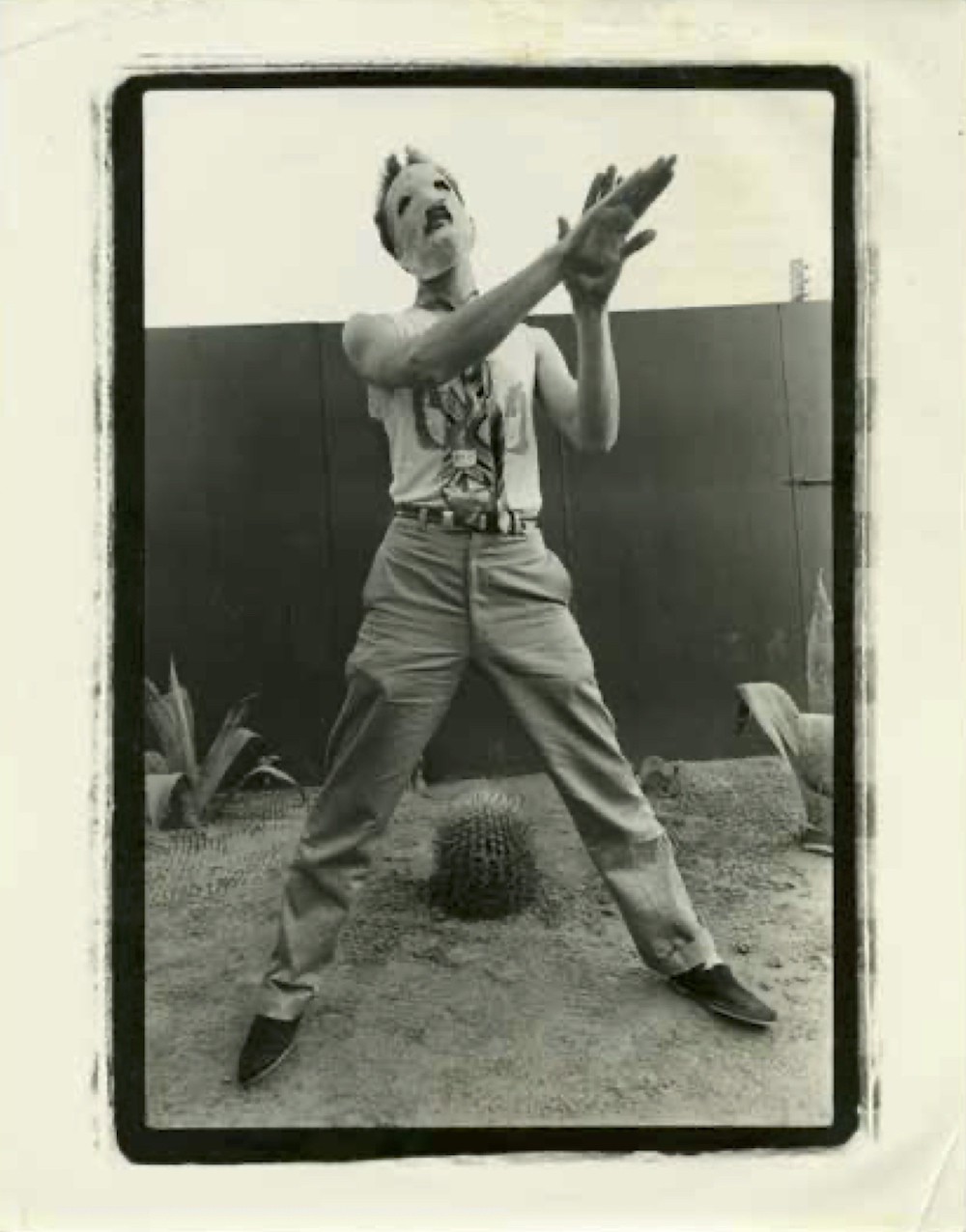

Panter wearing an Apeweek mask in Los Angeles, 1978. The masks were “about Mexican wrestling, A Clockwork Orange, primitivism.” Photo: Melanie Nissen.

It was in this period that Panter formulated the concept of Rozz-Tox. The Rozz-Tox Manifesto ran in the L.A. Reader in 1979 as a series of personal ads, but the idea for it had begun in 1976 and was an extension of drawings he had made in college. The name drew from his teacher Lee Baxter Davis’s “Pox” series of etchings and from the term rozzes, meaning “police,” in Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange. The x’s and z’s implied something futuristic to Panter, and his original notion was to think about what comes after rock ’n’ roll. “Everything dies as a fad and cultural trend,” he says, “so I imagined some kind of noisy technological modern music.” Inspired by Panter’s reading of various manifestos and accounts of modern art, Rozz-Tox evolved into a phony art movement that not only described the end of Modernism but anticipated the kind of postmodern art that would take hold in the eighties: art that took as its subject, and sometimes its medium, advertising and consumer culture, imitating it in order to critique it—the photographic appropriations of the Pictures Generation, for instance, and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s palimpsestic paintings. “Our own creations have shamed us,” Panter writes in the manifesto. “Teaching us that the hand and opinion of the individual are not as legitimate as that of opinion transmuted and inflated by broadcast … Capitalism good or ill is the river in which we sink or swim. Inspiration has always been born of recombination.”

The Rozz-Tox Manifesto also encouraged finding alternative ways to make and situate art in the capitalist world—advice that has only become more urgent over time. It warns against relying on the “aesthetic” media to point you in the direction of what is good and worthy in art and culture; the individual should follow her own instincts, her own tastes. In other words, great art doesn’t exist only in the pages of glossy magazines.

In punk’s wake came rampant fragmentation and recombination, and Panter’s manifesto, playful and exaggerated, bloomed into this sweeping “postpunk” era. Simon Reynolds’s description of the period from 1978 to 1984 also encapsulates what Panter was up to then:

[Those years] saw the systematic ransacking of twentieth-century modernist art and literature. The entire postpunk era looks like an attempt to replay virtually every major modernist theme and technique via the medium of pop music … Lyricists absorbed the radical science fiction of William S. Burroughs, J. G. Ballard, and Philip K. Dick, and techniques of collage and cut-up were transplanted into the music.

When, as Reynolds reports, John Lydon threw off the Johnny Rotten persona and formed Public Image Ltd (whose name was taken, in part, from a Muriel Spark novel) in 1978, he thought of the group not only as a band but as a “communications company,” one that would intervene in other areas of media in order to demystify the music business and reimagine what it could produce. At the same moment, in California, the Rozz-Tox Manifesto declared, “If you want better media, go make it.”

*

Panter moved to New York in 1986. Before leaving LA, he designed the sets and puppets for Paul Reubens’s Pee-wee Herman stage show. In New York, Rubens asked him to do the same for his new television show, to be broadcast on CBS. Panter’s designs for Pee-wee’s Playhouse infused the atomic aesthetic of fifties LA coffee shops with Dubuffet’s aesthetic agnosticism and the vivid, mass media–inspired British Pop art that Panter admires, in particular Eduardo Paolozzi. “We put art history all over the show,” he said. Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise contains the same kind of recombination: a collage of styles that represents Panter’s thoroughgoing absorption of visual culture. It looks and reads as though it were composed by an otherworldly visitor with the whole of human civilization (at least up to the late eighties) at her disposal.

Adventures in Paradise gathered comics from Slash and Raw, together with new material and a handful of Panter’s “William and Percy” strips that ran in the L.A. Reader in the early eighties. The work was produced over a decade, from 1978 to 1988 (the majority dates from the late seventies and early eighties, and the opening and closing sections were the last to be made), but the sequences aren’t arranged chronologically. Instead, Panter organized them to create what he has described as a “rambling coherence.” The book’s mode is disjunction and unmaking—formally, in the salmagundi of page layouts and drawing styles (shifting effortlessly between Cubism, Neo-expressionism, Kirby, sixties Chicago figuration, Ukiyo-e woodcuts, and George Harriman, among others); narratively, as the story leaps, lurches (including a very funny jump cut), and finally explodes; and tonally, from punkish mischief to romance, cartoonish crime to outright atrocity.

It takes place in the near future, in Dal Tokyo, the Martian city run by corporations, and which illustrates Panter’s play-set approach: all the toys and cartoon characters, punks, weirdos, and aliens set in motion in one huge sandbox. He titled the book Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise, though he hadn’t yet read Dante and the book has nothing to do with the Paradiso. (Still, Dante’s celestial theology is arguably no less a radical science-fiction vision of the vast smallness of the universe than Panter’s sociocultural stew bubbling on Mars.) Of his very early career, Panter said, “in some ways you accept your vision or you don’t, and I keep having more and more visions and just moving to the next one to see how far I could go.” It’s an apt description of Adventures in Paradise, too.

The book begins with a soliloquy by Jimbo as he makes his way through the city to a neighborhood Feedomat, a fast-food joint in which orders are transmitted to robots by thought (it’s peak surveillance capitalism):

Have you ever had a dream where you knew you were dreaming, but it was so real that you didn’t trust your judgement? And you thought “Well, maybe it did get this bad, but it got bad so fast and so different!” So then you thought “Nah! It’s just a dream. Things aren’t this bad yet!” When suddenly, it all seemed feasible again … And so boring and normal—convincing—like any other day.

The slippage between dream, nightmare, and reality is a hallmark of Adventures in Paradise, which rambles, and sometimes veers, among different states of reality, some to be believed and others not. It is antic and outrageous, a convocation of childhood wonders that might convince us that “dreams are toys,” as Antigonus reasons in The Winter’s Tale. Jimbo, despite his punk lineage, is no nihilist, no anarchist. He has more in common with a small-town Texas boy gazing rapt at the glowing screen of a drive-in; he is an empathetic and enthusiastic observer, like his creator. “I never jumped in the mosh pit,” Panter says. “I stood in the back, or on the sides, or even backstage, observing.” When Jimbo goes to a show at the beginning of the book, he complains about the fashion—the rubber pants are too tight and he can’t afford the fake scars that everyone wears. And Panter draws him just at the edge of the crowded pit, remarking on, but not joining, the fray. By book’s end, however, the dream does offend. Panter depicts a reality so nightmarish it couldn’t possibly be true, but is.

Jimbo’s adventure takes him from his mansion high on a green hill, “gigantic but condemned” (a lapsed Eden, not so far from Paradiso after all), to a crowded, kaleidoscopic music show–turned–riot that unravels in hallucinogenic wonder when he drops acid. Rifts tear at the panels and page gutters, nebulous forms that reproduce the way shapes dissolve into one another during an acid trip, but portals, too, opening to parallel planes of existence. He meets Smoggo, the smog monster, and falls in love with his unflappable sister, Judy, the unsung hero of the book who, when she is kidnapped by cockroaches, declares, “Jimbo, it won’t break my heart if I have to save myself!” (She does, too.) Meanwhile, King Ducko and his cockroach lackeys want the plans to the Radioactive Planetoid Burger Bar Corp.—or else. Laced within this main story are strange interludes, starring Rat Boy, Nancy and Sluggo, and Jimbo Erectus, as well as a (self-)critical fable about the United States’ exploitation and debasement of Native Americans.

The book coheres because it doesn’t try to. It runs on artistic adrenaline, unalloyed energy, and the joy of drawing. Its ruptures and tangents embody the social upheaval of the late seventies and eighties, and Adventures in Paradise, perhaps more than any other comic by Panter (or by anyone, for that matter), inextricably links avant-garde and popular culture into a single work full of feeling and ideas. It runs hot like a punk song and yet its hero is a sensitive hippie. “It was rude and so weird and not readable—all of the things that made comics narratively legible are part of the sabotage that is Jimbo,” Spiegelman recalls of the comic’s reception among general readers. For all the book’s fragmentation, Jimbo is fully alive as a character. As Smoggo tells him, “You’re litrature, buddy.”

In 2014, writing about his memory of visiting the hippie shack in California, Panter recalled the aura of activity in the place. This “evidence of doing,” as he calls it, links the process of making to the body itself. In thinking about that experience, he observes that H. C. Westermann’s work “radiates powerful vibes of having been intensely touched, refined.” He comments, too, on “the ears of Peter Saul’s mind, the hand craft of Nutt, and Wirsum.” Markmaking (or objectmaking) is, for Panter, a process that conjoins knowledge or emotion and physicality. “Drawing is a way of controlling your world if you can control your hand,” he has said. His love for movies in which special effects are visibly human-made finds expression in his unpolished, ratty line—his distinctive drawing style that evidences its own handmade-ness.

In Adventures in Paradise, he dedicates a story from 1979 to “the Guardians of the Ratty Line, who are Bringing it to its proper place in society”—among them, Matt Groening, Edwin Pouncey (a.k.a. Savage Pencil), Cal Schenkel, and Jeffrey Vallance. The camaraderie reminds me of Bernard Sumner’s first impression of the Sex Pistols: “I saw the Sex Pistols. They were terrible. I thought they were great. I wanted to get up and be terrible too.” Looking back on Raw’s publication of Panter’s Jimbo comics, Spiegelman has said: “There’s a separate moment in comics’ trajectory that indicates some new sensibility coming in. Gary was the clearest version of what that might be, as separate from what I’d known up to that point in underground comix.” Mouly saw in the work a “sense of what could be happening now and could be the future of comics.” Panter, always looking to see what comes next, had created the next thing.

*

At the end of the Adventures in Paradise, Jimbo must disarm an atomic bomb; he fails. The story overloads, narratively and visually, in one of the most masterfully drawn sequences of the medium. Panter composes each page in a different style, forms dematerializing and recombining in a new state, atoms rearranging. He studied books on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and modeled the comic’s backgrounds on what he read. He has described the ending as a “histrionic but heartfelt” meditation on the bombings of Japan as well as an attempt to address that “unsettled debt.” The nuclear threat was present as he drew those pages, too: in 1979, only a few years before he composed the atomic sequences, the Three Mile Island facility, in Pennsylvania, melted down. In a strip earlier in the book, drawn contemporaneously with the meltdown, Panter adds a winking aside to the reader: “No patriotic American would be mad if you, our society’s vandals, threw a brick through your nearest corporation that invests heavily in nuclear power.”

The cubist shards, moody ink washes, and spectacular arrays of breathless line work describe a puncture in time, a fragmented moment in which the present seems to leap forward in an instant. This existential doom is somehow elegant, as when Smithson, flying above his Spiral Jetty suspended in the Great Salt Lake, observes,

The flaming reflection suggested the ion source of a cyclotron that extended into a spiral of collapsed matter. All sense of energy acceleration expired into a rippling stillness of reflected heat. A withering light swallowed the rocky particles of the spiral, as the helicopter gained altitude. All existence seemed tentative and stagnant. The sounds of the helicopter motor became a primal groan echoing into tenuous aerial views. Was I but a shadow in a plastic bubble hovering in a place outside mind and body?

Panter’s pen dips into horror after horror, before alighting on the burned horse. Why a horse? His father, Panter once recalled, was “sentimental about horses and dogs and hates Western novels where the horse get killed. If anything bad happens to a horse in the story he’ll throw the book down.” The destruction of a horse was perhaps the best representation of barbarity Panter could think of. That final image, still and terrible: it evokes the obliterating silence that Dick describes in the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, “the lungless, all-penetrating, masterful world-silence.”

When Panter met Dick in LA in 1980, they exchanged stories about personal visions and the confusion that surrounded those visions. Panter told Dick about a bad trip he’d had in college, simultaneously foreboding and retrograde:

The pictures were coming at me ten thousand a second, and they were all relative, personal and manufactured. A lot of them were in the style of my art and most of them were wrong. They also seemed to be predictive, and I felt like a lot of what happened in my acid trip was like an echo of what I might experience later. As if giant trauma memories from the future would be impressed upon me as well as the past.

The time warp in Panter’s bad-trip hallucination—of the past pressing forward and the future echoing backward, both converging on the fleeting present—is a counterpart to Walter Benjamin’s terrifying vision of the angel of history:

His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But the storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

Both visions come to pass in the final image of Adventures in Paradise, in Jimbo—his horrible deed at an end, his head tilted back and away from the mangled body of the horse, the day done. Smoggo calls him “an unlikely custodian for a living nuclear nightmare.” Jimbo would have liked to repaired things but found the task impossible. He has been moving toward this moment from the first pages of the book, from a capitalist paradise, to the world in ruins, and then to whatever comes next.

Nicole Rudick is a critic and an editor. She has written widely on art, literature, and comics for The New York Review of Books, the New York Times, The New Yorker, Artforum, the Poetry Foundation, and elsewhere. She was managing editor of The Paris Review for nearly a decade and edited two issues of the magazine as well as The Writer’s Chapbook: A Compendium of Fact, Opinion, Wit, and Advice from “The Paris Review” Interviews.

Excerpted from Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise, by Gary Panter, published this week by New York Review Comics. Copyright © 2021 by Nicole Rudick, courtesy of New York Review Comics.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3dlqac6

Comments

Post a Comment