In 1935, Graham Greene spent four weeks trekking three hundred fifty miles through the then-unmapped interior of Liberia. As he explains in the book he subsequently published about the experience, Journey without Maps (1936), he wasn’t interested in the Africa already known to white men; instead, he was looking for “a quality of darkness … of the inexplicable.” In short, a journey into his own heart of darkness, to rival that of Conrad’s famous novel. As such, he knew that his recollections—“memories chiefly of rats, of frustration, and of a deeper boredom on the long forest trek than I had ever experienced before,” as he recalls in Ways of Escape (1980), his second volume of autobiography—weren’t enough. What he wrote instead was an account of this “slow footsore journey” in parallel with that of a psychological excursion, deep into the recesses of his own mind. Rather ironically, though, in 1938, his traveling companion published her own record of their expedition, and it was precisely the kind of account—what he’d looked down on as “the triviality of a personal diary”—that Graham himself had taken such pains to avoid.

Even if you’ve read Journey without Maps, you might struggle to remember Graham’s co-traveler. Understandably so, since she’s mentioned only a handful of times, and always only in passing. It’s easy to forget she’s there at all. But she was: his cousin, twenty-three-year-old Barbara Greene, who’d gamely agreed to accompany him after one too many glasses of champagne at a family wedding. “Liberia, wherever it was, had a jaunty sound about it,” she endearingly recalls. “Liberia! The more I said it to myself the more I liked it. Life was good and very cheerful. Yes, of course I would go to Liberia.” Such innocent, rose-tinted enthusiasm obviously doesn’t last, but as she goes on to explain, “By the time I had found out what I had let myself in for it was too late to turn back.”

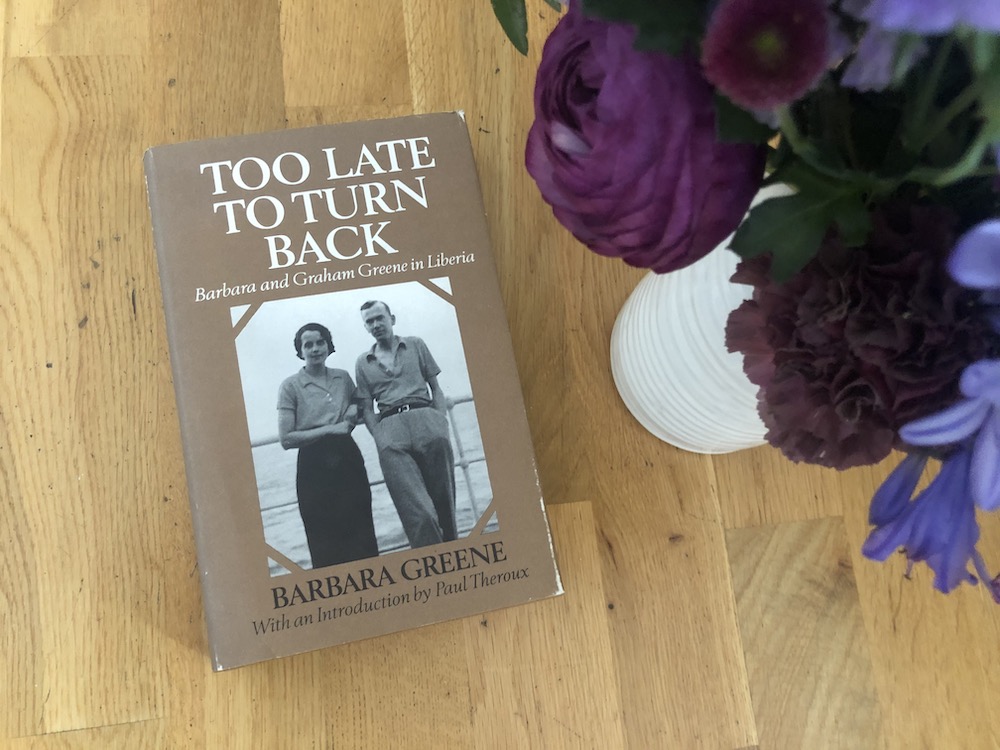

Originally published as Land Benighted, it’s the later edition—published in 1981, with the catchier title Too Late to Turn Back and a new foreword by the author, as well as an introduction by the acclaimed travel writer Paul Theroux—that’s probably better known. Even so, it’s been out of print now for nearly forty years, something that most likely wouldn’t upset Graham: although Barbara proved “as good a companion as the circumstances allowed,” where she did “disappoint” him, he admits in Ways of Escape, was in writing her book.

Fans of Graham’s work will undoubtedly claim that Barbara’s book is the less impressive of the two—the poor relative, if you’ll indulge me—but I’m not quite so sure. Too Late to Turn Back has its own merits and charms, and Barbara’s writing is not without flair. Had Graham not documented the journey himself—indeed, had he been just an ordinary Englishman abroad—Too Late to Turn Back could absolutely have stood alone as an illuminating and informative account of this tour through unknown territory. That it also provides an intimate observation of one of the most famous British writers of the twentieth century is the icing on the cake. As Theroux wrote in 1981: “What might have seemed trivial or unimportant about Too Late to Turn Back in the Thirties, now—over forty years later—is like treasure. What if Waugh had had such a companion in Abyssinia, or Peter Fleming’s cousin had accompanied him to Manchuria? What if Kinglake, or Doughty, or Waterton had had a reliable witness to their miseries and splendours? We would not have thought less of these men, but we would have known much more of them.”

*

Although first cousins, Graham and Barbara were not especially close. As she amiably explained in the foreword to her book’s 1981 edition, “He was trying to persuade someone, anyone, to go with him, and only after everyone else had refused did he ask me.” As in the book proper, she’s extremely self-effacing, recalling that the morning after they’d made their grand plans, and with their champagne hangovers now kicking in, both had regrets: “Graham because his heart sank at the thought of having to be responsible for a young girl he hardly knew.” That Barbara turned out to be a more spirited and obliging companion than her cousin could have dared to hope for must have come as a welcome surprise, but to begin with, there’s a certain wariness on both sides.

On their arrival in Sierra Leone’s Freetown, she jots down her general impressions of Graham in her diary. “His brain frightened me,” she begins. “It was sharp and clear and cruel. I admired him for being unsentimental, but ‘always remember to rely on yourself,’ I noted. ‘If you are in a sticky place he will be so interested in noting your reactions that he will probably forget to rescue you.’ ” Luckily, no such instance came to pass, but it is telling that in Ways of Escape Graham readily admits to having been all the more surprised by Barbara’s book because he “hadn’t even realised that she was making notes,” so focused had he been on his own.

“For some reason he had a permanently shaky hand, so I hoped that we would not meet any wild beasts on our trip,” Barbara writes. She continues:

I had never shot anything in my life, and my cousin would undoubtably miss anything he aimed at. Physically he did not look strong. He seemed somewhat vague and unpractical, and later I was continually astonished at his efficiency and the care he devoted to every little detail. Apart from the three or four people he was really fond of, I felt that the rest of humanity was to him like a heap of insects that he liked to examine, as a scientist might examine his specimens, coldly and clearly. He was always polite. He had a remarkable sense of humour and held few things too sacred to be laughed at. I suppose at that time I had a very conventional little mind, for I remember he was continually tearing down ideas I had always believed in, and I was left to build them up anew. It was stimulating and exciting, and I wrote down that he was the best kind of companion one could have for a trip of this kind. I was learning far more than he realised.

Such behind-the-scenes insights into Graham’s state of mind continue, often set up in contrast to her own breezier attitude. For example, she notes that while she had packed the entertaining stories of Saki and Somerset Maugham, he was lugging The Anatomy of Melancholy through the jungle. But she’s also a wonderful source of more lighthearted tidbits. Take their habit of handily resetting their watches—which were continually stopping—to cocktail hour: “I don’t think it’s too early to have a drink, do you? Let’s put our watches at six o’clock.” (I’d be keen to find out exactly how much whiskey they packed, since both books are literally sloshing with the stuff.) Or the delight with which they indulge in spoonfuls of golden syrup—having suddenly “developed a startling love of sweet things”—as their rations grow increasingly meager, Graham dreaming all the while of steak-and-kidney pudding. And although their companionship is remarkably placid, Barbara finds herself strangely fixated on Graham’s socks, which, not held up by garters, annoyingly fall in “little round wrinkles, like an old concertina” round his ankles. He, she later learns, is equally perturbed by her horrendous hiking shorts, the unflattering shape and cut of which are “almost more than he could stand.”

On a more serious note, she also records the manner with which Graham deals with the local men. Despite having been told by various white people in Freetown that the locals will respect nothing but “a yelling voice and a heavy hand,” Barbara reports that Graham instead “treated them exactly as if they were white men from our own country.” (Given the ingrained racism of the day, I doubt that this is quite true—not least because she then goes on to describe him as acting like a “benevolent father” toward them—but he would appear significantly less draconian than some.) Most valuable of all, though, is Barbara’s recollection of just how very ill Graham becomes toward the end of the trip. The twitching nerve that she notices over his right eye whenever he’s ailing starts going like the clappers, his face is gray, and for a while, at least, he seems to be propelling himself by means of “will-power” alone. His eventual collapse—which he glosses over in Journey without Maps, by means of the dismissive section heading “A Touch of Fever”—leaves Barbara absolutely convinced that he’s dying: “I never doubted it for a minute … He looked like a dead man already.” Struggling as she is with extreme exhaustion herself, she’s able to focus on only “the practical side of it all,” becoming fixated on the particular problem of not having any candles to burn in the event of her Catholic cousin’s death. “I could not remember why I should burn candles,” she writes, “but I felt vaguely that his soul would find no peace if I could not do that for him. All night I was troubled by this thought. It seemed to be desperately important.”

This episode sums up Barbara’s character and attitude in more ways than one. Overall, reviewers praised her “pluck” and sense of adventure, her book thus presumably appealing to readers who had gobbled up E. Arnot Robertson’s best-selling novel Four Frightened People (1931), another story of the wild and thrilling adventures of two young English cousins (and which, coincidentally, Barbara reads during the voyage out to Africa). In that book, Judy Corder, a twenty-six-year-old doctor, her cousin Stewart, and two other English passengers flee the boat on which they’re traveling through Malay to Singapore because of an outbreak of bubonic plague, only to then be confronted with the dangers of the jungle instead. For her part, Barbara does warn readers that despite all the talk of wild animals and cannibals then still associated with Liberia, those hoping for a “roaring lion type of adventure” might be disappointed since her and Graham’s capers “were more amusing than frightening, and good luck dogged our footsteps most of the time.”

She might not have been relating an excursion to rival Judy’s—which involves deadly snake bites, tropical storms, and poison dart–armed natives—but nevertheless, Barbara can write, and what her tale lacks in thrills she makes up for in the sharpness of her observations. If Graham’s book is a journey into the dark interior of his mind, Barbara’s is the lighter counterbalance. Not only are her descriptions more grounded in the cousins’ bodily experiences, but she brings an altogether different point of view to proceedings. Describing an especially hard uphill slog, for example, she likens herself to “some poor creature in a Walt Disney film, wending a heartbreakingly cruel way up a twisty, winding road to the wicked castle lying high up on the mountainside” It’s an image that works rather well, perhaps precisely because one could never imagine reading it in Graham’s account.

*

Barbara’s adventurous streak continued long after she’d left the Liberian jungle. Shortly after her return to England, she followed another cousin, Graham’s brother Hugh, abroad to Berlin, where he was a foreign correspondent. There she fell in love with a German diplomat, Count Rudolf Strachwitz. Increasing political tensions scuppered their plans to marry, but Barbara stood her ground, remaining in Germany rather than fleeing for the safety of Britain during World War II. According to her obituary in the Guardian, which ran in 1991, when she died at age eighty-four, “a large circle of loyal friends (many of them later involved in the July 20 plot to assassinate Hitler) did much to protect her, but her life was precarious.” Her every move was watched by the Gestapo—their suspicions having been further fueled by her association with Bishop Preysing, an outspoken critic of Nazism, from whom she received instruction after she converted to Catholicism (once again following in the footsteps of Graham)—and the only work she could find was as a cleaning lady.

She and Rudolf did manage to marry in the spring of 1943; she became Countess Strachwitz, but he lost his job at the Foreign Office. He was then called up, leaving Barbara pregnant and alone in Berlin as the Russian army advanced on the city. Like many others, she fled west; she suffered a miscarriage in the process. While Rudolf was taken prisoner by the Americans, she sought refuge in Liechtenstein (Prince Franz Joseph II’s sister was married to Rudolf’s younger brother), and her sojourn there later inspired her second book, Liechtenstein: Valley of Peace (1967), a warm and sympathetic sketch of the tiny country and its people.

For a long time neither husband nor wife knew if the other was still alive, but they were eventually reunited in 1946, and two years later they emigrated to Argentina, where Rudolf got a job teaching economics (a subject in which he held a doctorate) at the University of Mendoza. They went on to have two children, moving to Berchtesgaden, the picturesque town in the Bavarian Alps that had once been the site of Hitler’s infamous Eagle’s Nest retreat, on the occasion of Rudolf’s retirement, and Barbara published her third book, an anthology of prayers. When Rudolf died, in 1969, she moved to Gozo, a small island of the Maltese archipelago in the Mediterranean Sea, where she dedicated much of her time to caring for disabled people. Frustratingly, despite such an eventful life, Too Late to Turn Back was the only volume of memoir she published—fittingly so, perhaps, since as the Guardian obituary closes, “She declined to write her autobiography; she lived for today and tomorrow, but never for yesterday.”

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, the Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review, and Literary Hub, among other publications. Read earlier installments of Re-Covered.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3m6M07l

Comments

Post a Comment