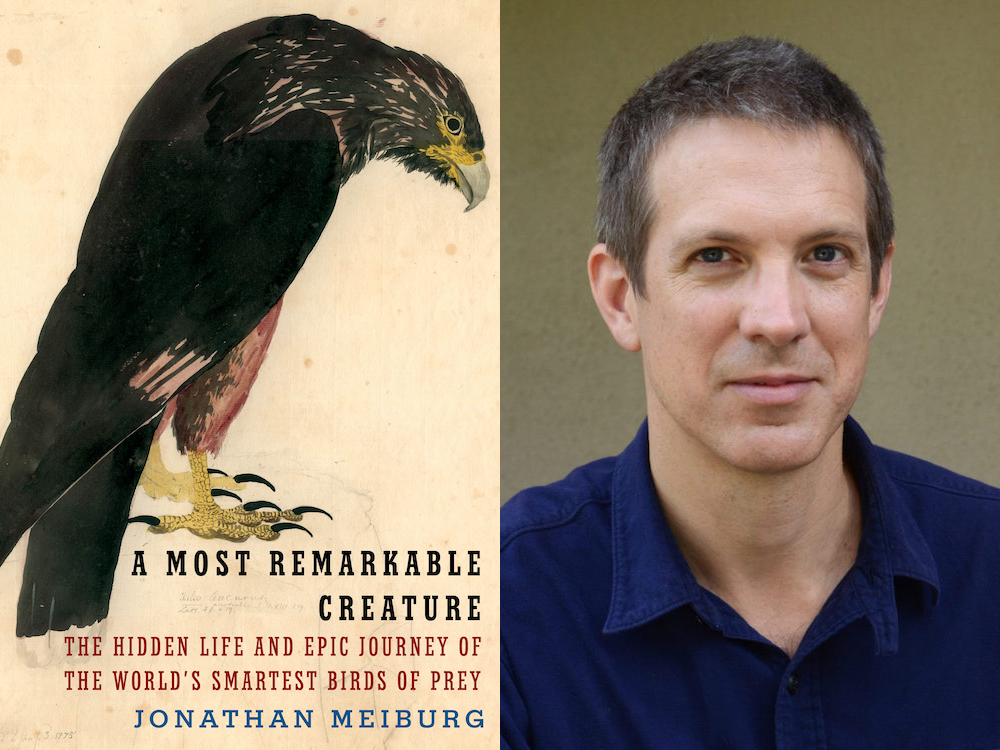

Jonathan Meiburg was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1976 and grew up in the southeastern United States. In 1997, he received a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship to travel to remote communities around the world, a year-long journey that sparked an enduring fascination with islands, birds, and the deep history of the living world. Meiburg explores these passions in his new book, A Most Remarkable Creature, which traces the evolution of the wildlife and landscapes of South America through the lives of the unusual falcons called caracaras. Like the omnivorous birds at the heart of his book, Meiburg is more generalist than specialist. He’s written reviews, features, and interviews for publications including The Believer, Talkhouse, and The Appendix, on subjects ranging from the music of Brian Eno to a hidden exhibition hall at the American Museum of Natural History. He also conducted one of the last interviews with Peter Matthiessen. But he’s best known as a musician—albums and performances by his bands Loma and Shearwater have earned critical acclaim for many years, often winning praise from NPR, the New York Times, the Guardian, and Pitchfork. In 2018, Meiburg organized and performed in a three-night live reconstruction of David Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy for WNYC’s New Sounds program. He lives in central Texas. This interview was conducted electronically between there and Wilmington, North Carolina.

INTERVIEWER

Recently an anhinga started roosting by the tidal creek that runs through my backyard. It’s fun to watch—the long snaky neck and the way it hangs its wings out to dry like laundry. Once, when the creek was clear, I watched it hunt, and it flew along underwater like a fish. I’ve been told that anhingas aren’t really supposed to be here, or that this is north of their range, which is shifting due to climate change.

MEIBURG

To me anhingas are among the most beautiful birds, and maybe the most like their dinosaurian ancestors of any birds. A lot of people think they’re sort of goofy, and I can see that, too—the tiny heads, the absurdly long necks and flight feathers, the overall sense that they’re a prototype someone meant to refine later. They have wonderful nicknames like “snakebird” and “water turkey.” I love how you can see them soaring way up in the sky for no apparent reason, like ravens with long, skinny necks, even though they make their living wading around on the bottoms of rivers.

They need to stay underwater for a long time, so they have very little oil on their feathers. This helps them sink and stay down. But it means they have to spend a lot of time standing on perches and holding their wings out to dry, which is usually how you see them, and it locks them out of places that get really cold. I was used to seeing them in the southeastern U.S., especially along that elevated stretch of I-10 that crosses the Atchafalaya Basin—but they were thick along the river in southern Guyana when I visited, and they seemed completely at home among colorful, feathered weirdos like parrots, toucans, and capuchin birds.

INTERVIEWER

What role does this movement of animals between South and North America play in your story? I think of it all as one big blob of land with a canal in the middle.

MEIBURG

This question is pretty much at the heart of my book, which starts with Darwin scratching his head about why the striated caracara, a bold, social, curious bird of prey he met at the southern tip of South America, lived there and nowhere else. Trying to figure that out changed the way I thought about the world.

INTERVIEWER

Expand on that, for those of us who don’t instantly make the connection between “strange bird confined to the southernmost part of South America” and “the world.”

MEIBURG

Until I started trying to understand where the caracaras came from, I’d never realized that North and South America, biologically and geologically, are basically strangers to each other. Lumping them together as a single “New World,” as Europeans did, really doesn’t make much sense. Tectonic forces kept the Americas apart for a hundred million years. When they finally joined hands at the isthmus of Panama a few million years ago—a short time, if you’re a paleontologist—two sets of animals who’d pursued completely separate evolutionary journeys confronted each other, which one scientist called “one of the most extraordinary events in the whole history of life.”

Caracaras are part of this story. Like the parrots, their ancestors probably entered South America through the forests of a warm Antarctica, and in the southern New World they mostly play the same roles crows play here—clever, social scavengers, like raccoons with wings. But unlike large crows, which have never found a foothold in South America, caracaras made it to the northern hemisphere thousands of years ago. We’ve found their fossil bones in California and Arkansas, and although they retreated south after people arrived in the Americas, they’re slowly coming north again. The website eBird says they’ve been seen recently in the Outer Banks.

INTERVIEWER

How did you settle on that bird in particular?

MEIBURG

What hooked me was their personality. Beside the fact that they’re big, flashy birds of prey that behave more like crows, striated caracaras just don’t act like wild animals are “supposed” to. They swagger up like they’ve got as much right to be here as you do, and look you right in the eye. If you sit still they’ll start trying to take things out of your bag. I have a little video of one trying to figure out what to do with a pair of hiking poles. They’re utterly and confidently themselves, and they made me realize that the reactions of every wild animal I’d ever seen—hiding or fleeing in terror—weren’t how it always was. Animals had to learn to do that, from bitter experience.

INTERVIEWER

Any chance you’d share that clip?

MEIBURG

Here it is.

I should make clear that by “caracaras” I mean all ten species, a unique lineage of odd falcons that lives mostly in South America. Striated caracaras are the rarest, but they’re all equally wonderful in their own ways. One tropical species, for example, lives in large family groups that raise one chick at a time, and survives on a diet of wasps’ nests and fruit. They all appear in the book. There’s no such thing as “the caracara” any more than there’s a bird called “the eagle.”

INTERVIEWER

You were approaching these birds as a naturalist. When did they turn into a book?

MEIBURG

A long time ago, you told me, “Never write a book if you can help it.” I couldn’t help it. Before I met striated caracaras, I’d vaguely thought scientists knew most of what there was to know about animals, especially animals surrounded by celebrity wildlife like penguins and whales, so I was naively surprised that I’d never heard of these unusual birds, then genuinely surprised at how little was known about them—even though they’d also transfixed Darwin, who wondered the same things. What were they? Why did they act like this? Why did they live at the bottom of the world and nowhere else?

INTERVIEWER

You’ve mentioned Darwin, but surely some other people or peoples noticed them, even so far south.

MEIBURG

Oh, yeah. The Inca emperors were allowed to wear the feathers of Andean caracaras, and dancers dressed as these birds still feature in solstice parades in highland Ecuador and Peru. A crested caracara showed the Aztecs’ ancestors where to build Tenochtitlán—now Mexico City—and Toba people in northern Argentina told an ethnographer from the United States that the supernatural hero Carancho—another name for a crested caracara—entrusted humans with the secrets of fire and medicine.

When you compare that with the way Europeans regarded striated caracaras in the Falklands, it’s hard not to shake your head. Sealers and whalers called them “flying devils,” and the enterprising colonists who turned the islands into a sheep farm the size of Connecticut slapped a bounty on the birds’ beaks, nearly driving them to extinction. A marooned sealer declared them “the most mischievous of all the feathered creation,” and even Darwin called them “false eagles” who “ill become so high a rank.” They’re protected now, and minds are changing—though as I say in the book, I’m not sure how much time they have left if we don’t take some fairly wild measures to save them. There are about the same number of adult striated caracaras as there are giant pandas in the wild.

INTERVIEWER

Is it true that we were once members of a nameless band that did two benefit shows then instantly broke up?

MEIBURG

I’ve never admitted it in public.

INTERVIEWER

Is it also true that you are now in a pretty famous band called Shearwater that just put out a record produced by Brian Eno?

MEIBURG

Not quite. Shearwater has done seven albums for Matador and Sub Pop since 2006, and I’m working on an eighth right now. As for Eno, he mixed the final track, “Homing,” on the most recent album by Loma, a band I started a couple of years ago with Emily Cross as the singer. He shouted out our first record on the BBC at the end of 2018, which helped get us in gear for a second. Weren’t you on the same radio program with him when I saw you last in NYC?

INTERVIEWER

Bri? We’re like the same person. We go shooting. There was a radio thing. Listen, though. Your book grows out of your work as an ornithologist, and your band is named after a bird, and I’ve seen you perform songs about birds. You did one here in Wilmington. What’s it all about?

MEIBURG

Paying close attention to birds draws me out of myself, which I crave more and more as I get older. Music does exactly the same thing—it gives you the feeling of being humbled and exalted at once.

John Jeremiah Sullivan is a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine and the Southern editor of The Paris Review. His latest work of fiction, “Uhtceare,” appears in the Spring issue.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3azwJax

Comments

Post a Comment