I don’t know how old I was when I first read Shary Flenniken’s Trots and Bonnie, but I definitely wasn’t old enough. I was a precocious reader and pretty sex-obsessed for a child, and my parents would buy National Lampoon every now and again and leave it where it could fall into my unsupervised little hands (parenting was a different animal entirely in 1984, kids). I couldn’t have been more than seven, but the experience is as clear and vital as if it happened yesterday: here was something that looked friendly and kidlike, but it was dangerous. It was confusing, it was weird, and it was very, very hot.

By the time I came of age, I had put National Lampoon on my mental back burner. I wouldn’t say I forgot about Trots and Bonnie, but I’d stored it away deep in my subconscious, where it formed a bedrock of my sensibility I wouldn’t recognize until years later. When I reacquainted myself with the strip in my twenties, it was like seeing a long-lost and deeply beloved friend. I also realized I’d been ripping Shary off for years. Those blank Little Orphan Annie eyes, the cheerful willingness to be absolutely disgusting, the heady mix of raunch and innocence—all things that had percolated through my own mind and heart and spilled out into my own work, a dim echo of the masterful original.

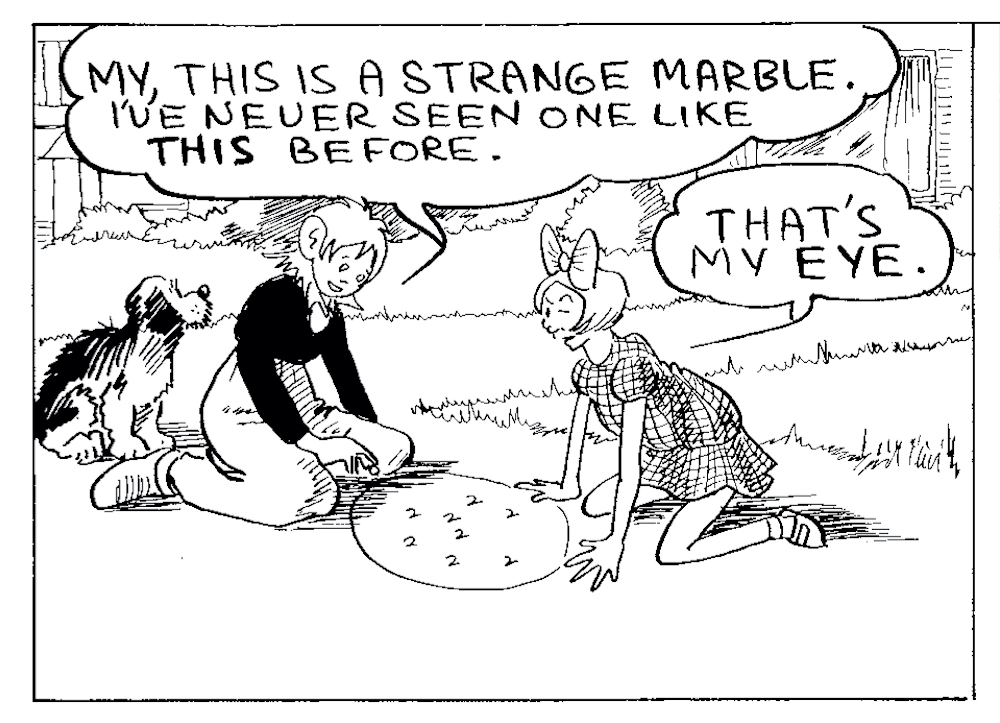

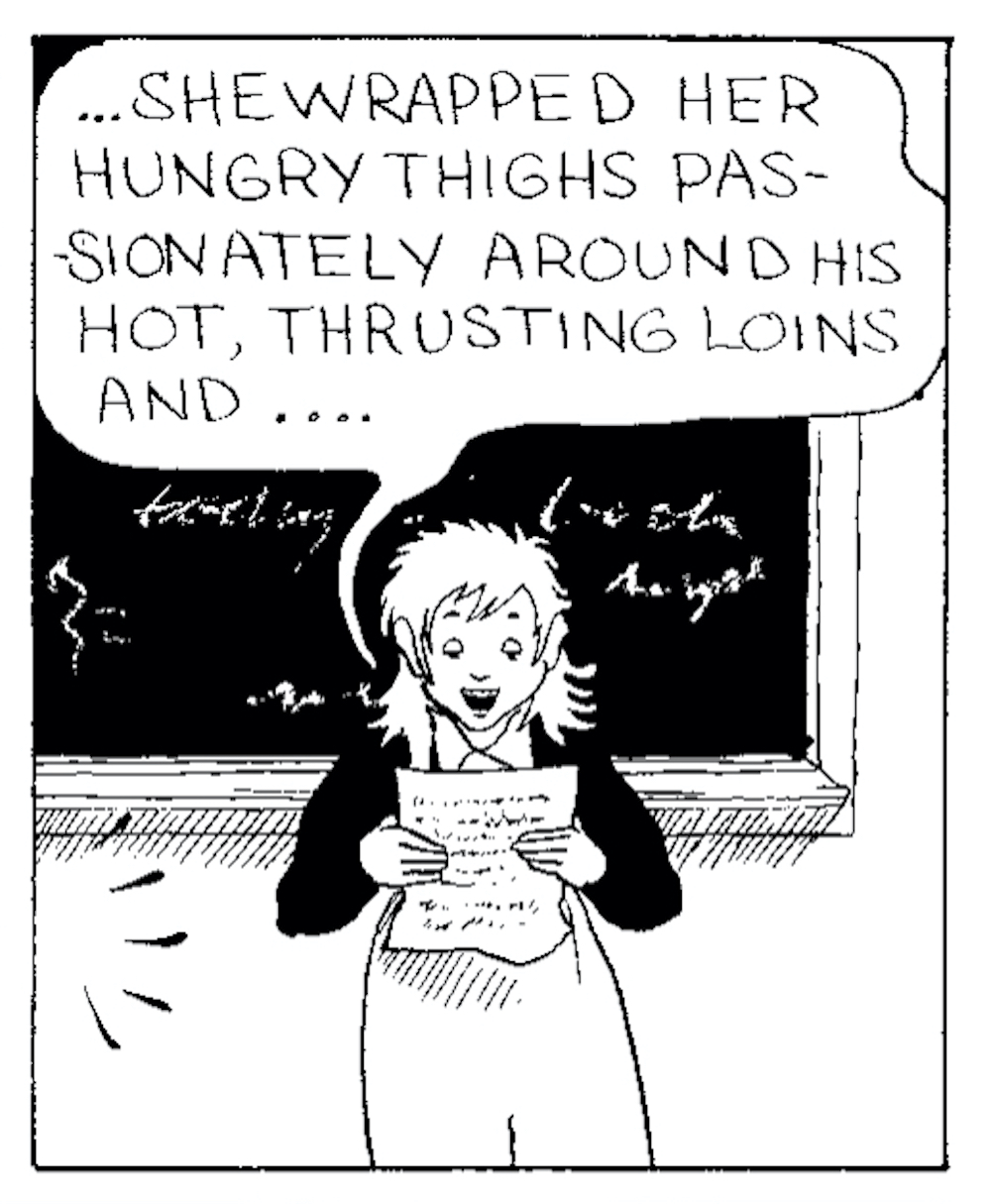

How to explain Trots and Bonnie to the uninitiated? It’s a bit like Little Nemo, if Little Nemo had been drawn for and by pervs. The titular characters are a girl in early adolescence, Bonnie, and her wry, horny dog, Trots. Bonnie stands as a kind of wise-fool character, observing the often hypocritical, sometimes hedonistic world around her with the candor and freshness of a child and the lust of a dirty old man (if parenting was different in the eighties, cartooning was different in the seventies: a strip featuring a young teen rubbing one out to literary porn penned by her dog might raise more lawsuits than eyebrows in today’s cultural climate). Bonnie’s floppy trousers and slouching posture paired with Trots’s smart-cracking wiseacre role have antecedents in Bud Fisher’s Mutt and Jeff. The drawing is lyrical and lovely—all swooping lines and flat textures, like an Erté drawn in the girls’ bathroom at a particularly ill-run reformatory. Flenniken draws like an angel, but, like Caravaggio, prefers the company of sinners.

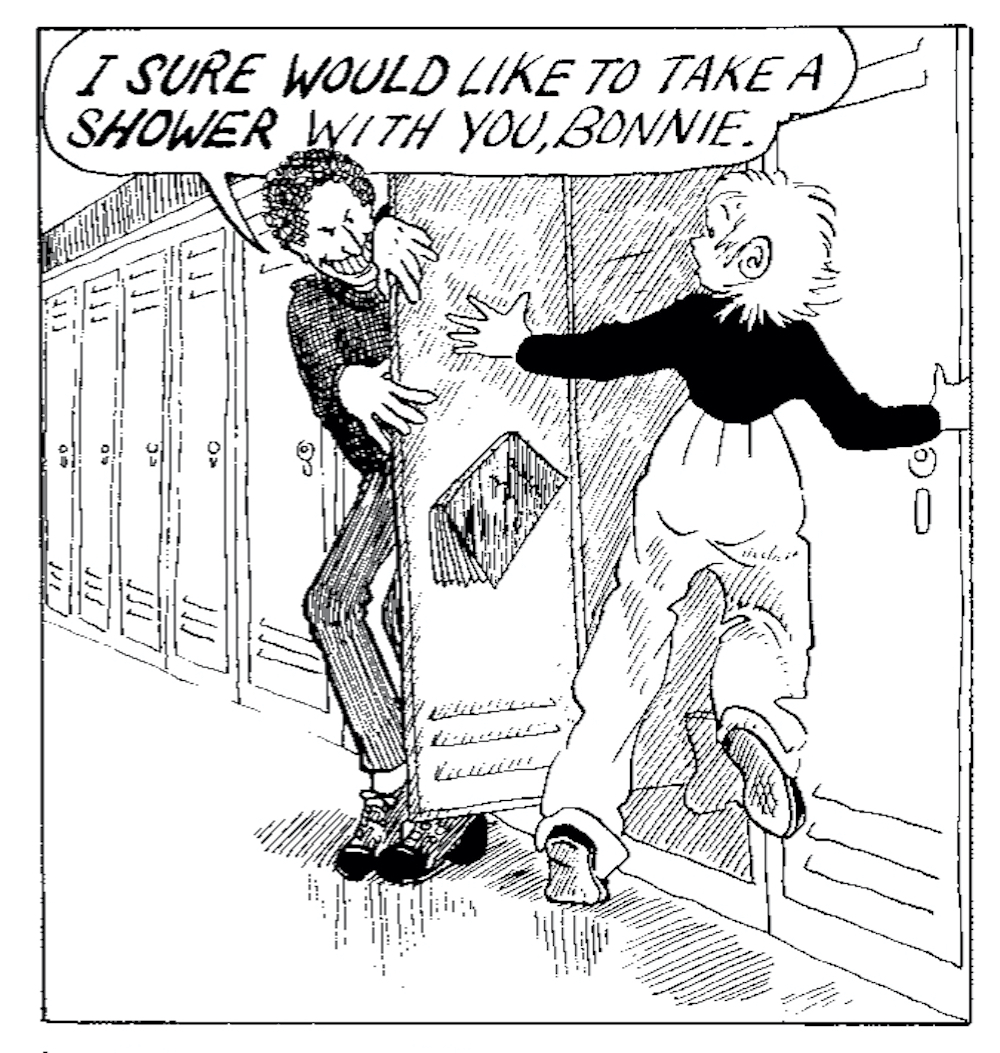

Bonnie’s adventures are more quotidian than Nemo’s, but no less wild. The lands between girlhood and womanhood are weirder and more unsettling than anything Winsor McCay ever dreamed up. The monsters traversing her landscape are real: neighborhood drunks, uncaring parents, and that biggest bogeyman of all, puberty. Yet she moves through the world with amiable good cheer, in danger yet never a victim. Her hair is a semi-androgynous shag; her high-waisted, baggy pants conceal the randy monster that throbs beneath. Her more worldly best friend, Pepsi, dresses in an incongruously childlike pinafore paired with fishnets, a perfect metaphor for the terrifying underage sex fiend she is. When Pepsi rhapsodizes about condoms or proclaims proudly that her perfect gentleman boyfriend has “the smallest cock in all eighth grade,” it’s both hilarious and deeply unnerving. Supporting character Elrod, a younger neighborhood boy, gets the worst of their impulses: shot, mutilated, and drowned like an X-rated Wile E. Coyote. Their world is brutal and lecherous and gross, yet suffused with heart and a fierce solidarity with the point of view of its main inhabitants.

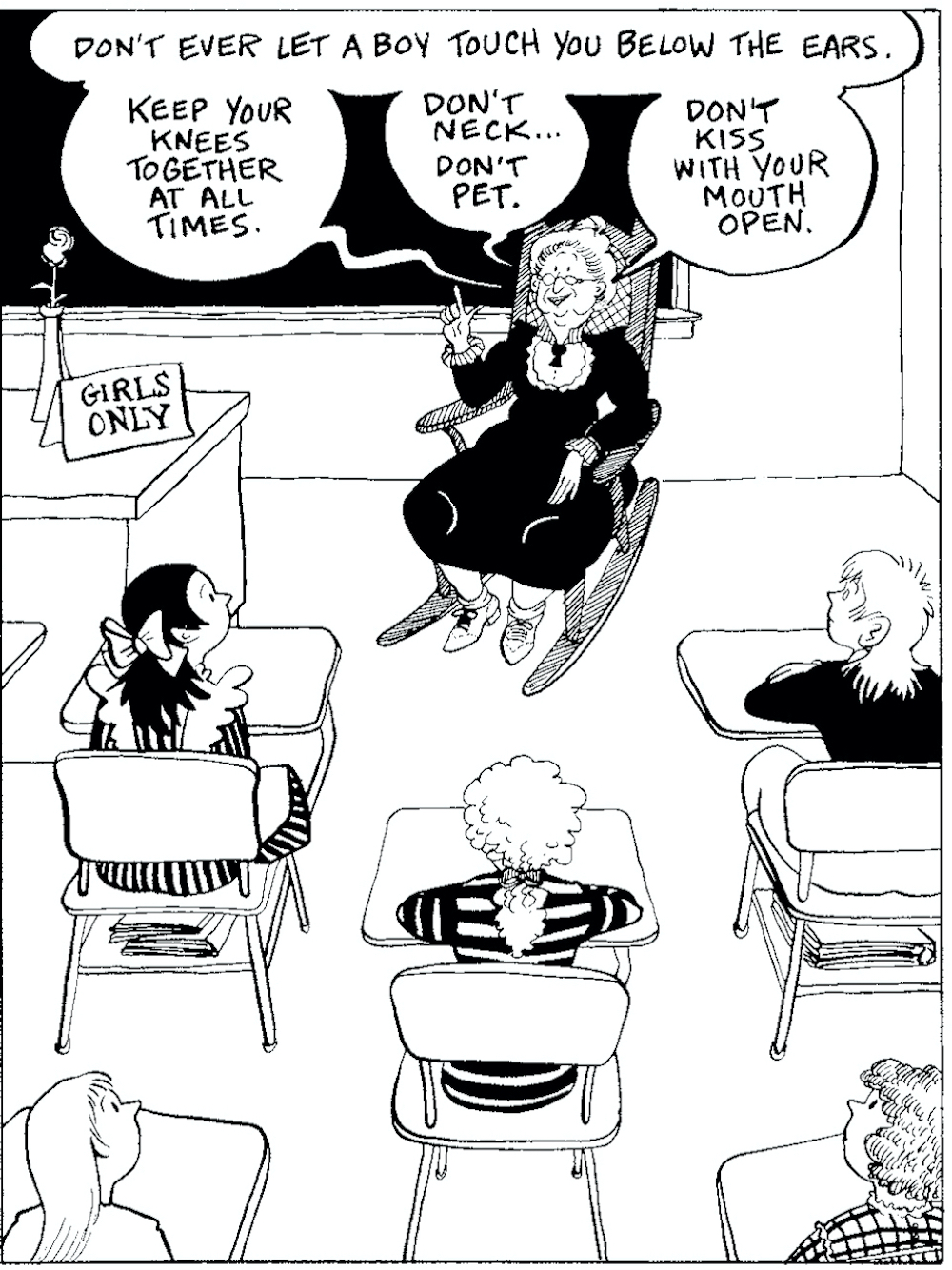

What Flenniken understands and brings gleefully to the page is that adolescent girlhood is positively feral and that teenage girls are both threatened and threats themselves. J. M. Barrie tells us in Peter Pan that children are “gay and innocent and heartless,” and that little weirdo had it right—that’s the terrible power of children, the monstrous innocence that makes them capable of anything, a state of being we fatuously describe as “pure.” You dump a bunch of hormones into a child’s body and all of a sudden you have this awful hybrid creature: a changeling with the self-centeredness and nonexistent impulse control of a child but the body and urges of a breeding-age adult. It’s a dangerous time in a young woman’s life, but as with most dangers, it has a messy, chaotic, super-hot fun side as well. To speak frankly of this fun side is tricky for adults, to say the least. We remember it, if at all, as a fever dream, a sticky, humid jungle of lust and stink. Grown-ups have to blind themselves to the sexual power of eighth-graders, for reasons I sincerely hope are obvious. But the kids can see each other head-on, and they wield their sexuality with all the grace and care of a toddler toting an AK-47. Flenniken dares to write and draw from that swamp with a complete lack of adult-world moralizing or editorial restraint. Arguably, “moralizing” and “restraint” weren’t really anyone’s bag when she was creating these strips, but there’s still an audacity in her work that I imagine felt as electrifying then as it does now.

Bonnie and Pepsi are obsessed with sex, but they’re not here for the male gaze. Their desire is frank and straightforward and more than a little demented, and it’s depicted with a bracing honesty that feels less like a political statement and more like Flenniken is reporting from the front lines with no filter, no safety net, and no intention of telling anything but the truth. Trots and Bonnie ran into the late eighties, but it was born from a seventies worldview, a decadent, anything-goes carnival where thirteen wouldn’t get you twenty. The hangover from this era was vicious and the societal course-correction necessary, but the importance of hearing from girls of the era rather than from the guys who liked to ball girls of the era cannot be emphasized enough. Bonnie isn’t masturbating on the toilet because she wants you to watch. She’s doing it because her body belongs to her and she’s horny as fuck.

As a child I was mystified and entranced by these strips. As a twenty-year-old, I was delighted anew by their bawdy, anarchic swagger and their pie-eyed charm. As a forty-two-year-old, I am so far from the lawless, deeply screwed-up Eden that Trots and Bonnie inhabits that it may as well be documenting life among the Stone Age clans. Part of me wants to call protective services—have I become a scold, or just a mother? Barrie tells us that those who are no longer gay and innocent and heartless can no longer fly. Being earthbound is the price we pay for our experience in this world, perhaps, and maybe to understand danger and value safety is to run the risk of identifying with the wing-clippers of this world. But looking at these strips I feel an echo of that old and savage glee, a distant memory from when I lived in those lands. Would I move back there if I could? Probably not, but we are so lucky to have in Shary Flenniken a cartographer of our most treacherous and rewarding landscapes. Would that we all had such balls.

Emily Flake is a cartoonist and illustrator. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Times, Time, and many other publications. Her weekly comic strip, Lulu Eightball, has appeared in numerous alternative newsweeklies since 2002. She lives in Brooklyn.

Excerpted from Trots and Bonnie, by Shary Flenniken, published this week by New York Review Comics. Text copyright © 2021 by Emily Flake. All images copyright © 2021 by Shary Flenniken.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2S94Y2h

Comments

Post a Comment