In Pardis Mahdavi’s new book Hyphen, she explores the way hyphenation became not only a copyediting quirk but a complex issue of identity, assimilation, and xenophobia amid anti-immigration movements at the turn of the twentieth century. In the excerpt below, Mahdavi gives the little-known history of New York’s hyphenation debate.

In the midst of an unusually hot New York City spring in 1945, Chief Magistrate Henry H. Curran was riding the metro downtown to a meeting at City Hall. Curran, the former commissioner of immigration at the Port of New York, and former president of the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment, had forgotten to bring his copy of the paper that morning. As a result, he found himself reading the various ads surrounding him on the colorful New York City subway.

Curran tried to focus on different advertisements to distract himself from the heat, and from his growing restlessness. Until, that is, one particular ad seized his attention. It was an ad for the “New-York Historical Society.” Innocuous enough at first, it was the tiny piece of orthography that caught Curran’s eye and sent a wave of heat through his body. Was that—could that be a hyphen? Sitting unabashedly between the words New and York? The anti-hyphenate politician was furious.

Curran swiftly exited the subway, marched into City Hall, and got his friend Newbold Morris, president of the New York City Council, on the phone. Later that week, the New York World–Telegram—oh, the irony of the hyphen placement in the publication that reported the incident—documented the conversation between Morris and Curran.

“This thing—this hyphen—is like a gremlin which sneaks around in the dark … you should call a special meeting of City Council immediately and have a surgical operation on it! We won’t be hyphenated by anyone!” Curran reportedly said to Morris.

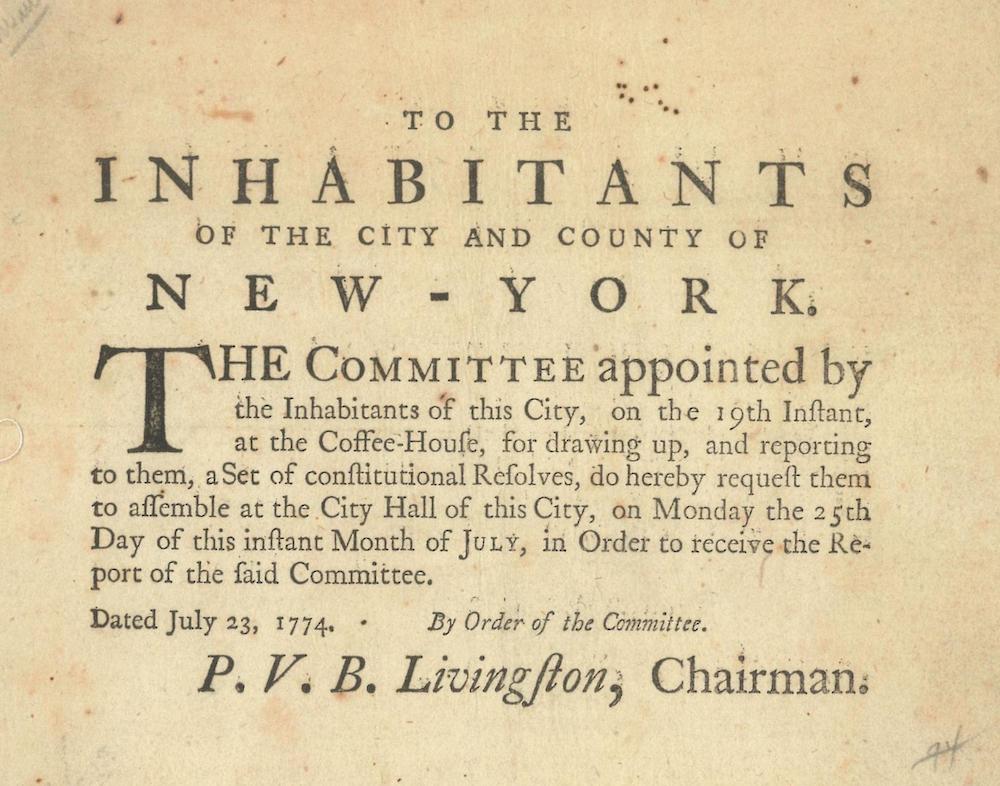

What Curran either didn’t know, or wanted to erase, was the fact that up until the late 1890s, cities like “New-York” and “New-Jersey” were usually hyphenated to be consistent with other phrases that had both a noun and an adjective. In 1804, when the “New-York Historical Society” was founded, therefore, hyphenation was de rigueur. The practice of hyphenating New York was adhered to in books and newspapers, and adopted by other states. Even the New York Times featured a masthead written as The New–York Times until the late 1890s.

It was only when the pejorative phrasing of “hyphenated Americans” came into vogue in the 1890s, emboldened by Roosevelt’s anti-hyphen speech, that the pressure for the hyphen’s erasure came to pass.

Curran was no exception to the wave of anti-immigrant xenophobia sweeping the nation at the time of Roosevelt’s speech and in the lead-up to World Wars I and II. During his time as commissioner of immigration, he penned a famous article that appeared in the recently unhyphenated New York Times entitled, “The Commissioner of Immigration Shows How He Is Hampered.” The essay was Curran’s response to outrage over the deportation of an immigrant mother who had arrived at Ellis Island with her young children, only to be sent back “home” while her children were to remain in the U.S. In the piece, Curran called for the public to afford the judges of such decisions “sympathy more than censure.”

Writing in 1924, several years after Roosevelt’s speech, Curran accused New York society of being overly judgmental, noting that “it is Ellis Island that catches the devil whenever a decision comes along that does not suit somebody. Of course, we are now in the midst of the open season for attacks on Ellis Island. We have usurped the place of the sea serpent and hay fever. We are ready to be roasted.” For the next twelve years he served as commissioner of immigration, Curran became more staunchly anti-immigrant, and his hatred was fueled by the anti–hyphenated Americanism espoused by people like Roosevelt and, later, Woodrow Wilson.

Curran was outraged that his beloved city would appear hyphenated, and he continually insisted that Morris call a meeting to pass a law that barred the use of a hyphen in New York. Meanwhile, curators, historians, and librarians banded together with antidiscrimination and immigrants’ rights defenders to defend a hyphenated New-York. Curran could not win this time, they insisted. The curators and librarians at the Historical Society bravely stood by the hyphen in their name, confirming that they had been founded in 1804, that the hyphen was in the original configuration of New-York, and that, no, this hyphen would not be erased. Hyphenated Americans and activists throughout New York City worried that this erasure would signal that they would not be welcome in the one city that was supposed to be a bastion of openness in America.

In the days leading up to the meeting, head librarian Dorothy Barch proclaimed that despite all of their research, no one had found any documentation indicating that the hyphen in New-York had ever been officially deleted by the government or any lawmaking body in the city, state, or country. The day before the meeting, curator Donald A. Shelley declared that they couldn’t even change their name if they wanted to because it is “chiseled in stone on the front of our building.”

The press and the pressure to enact an anti-hyphenation law were mounting in the lead-up to the meeting. Curran insisted that the hyphen was a scourge and that it should be erased completely, as it threatened to divide American society. In erasing the hyphen, Curran wanted to delete hyphenated Americanism altogether. He was firm: the hyphen divides, and as a divider, it threatened the future of the city, the state, the country. As he had done in his role as commissioner of immigration, he felt strongly that any immigrant or child of immigrants who identified as anything other than an American should be returned to whatever country was on the other side of that “filthy hyphen.” As such, he was emphatic in his attempt to whip the votes of his fellow council members in the lead up to the meeting.

All of this activity garnered a range of emotional reactions. Some people felt that this anger and energy, coming amid World War II, was misplaced. The upcoming meeting became the subject of mockery for artists and social commentators alike. At the meeting, a group of musicians and composers performed a song they had written entitled “The Hyphen-Song.” The words, written by popular songwriter Leonard Whitcup, included:

Take a boy like me, dear

Take the girl I’m dreaming of—

Add a hyphen, what’ve you got?

You got–UM–M–you’ve got love!

Me without you–you without me

It’s a sad affair—

But take a tip from the hyphen—

And baby we’ll get somewhere

The musicians performed to great acclaim. Activists gathered outside, tying ribbons to the stone etching of the hyphen to highlight the need to protect the orthographic mark that suddenly had so many political and social reverberations.

In the end, much to his chagrin, Curran lost this contest. No law was ever passed outlawing the hyphen, and it remains to this day, etched in stone on the building of the New-York Historical Society, a homage to the journey of the city and the hyphenated individuals who fought the good fight to keep the hyphen—and its many meanings—alive.

Today, the New-York Historical Society hosts hyphen festivals and blogs, and their softball team is named the Hyphens. Henry Curran died in 1966 at the age of eighty-eight. Before his death, and after his hyphen assassination attempt, he went on to be LaGuardia’s deputy mayor and the borough president of Manhattan. He died at Saint Barnabas Hospital in New-York.

Pardis Mahdavi is dean of social sciences in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and a professor in the School of Social Transformation at Arizona State University. She is a nonfiction writer with twenty years of experience as an anthropologist, a public health researcher, and an expert in sexual politics across the globe. She is the author of Hyphen, as well as five other books, including the first book on sexual politics of modern Iran, Passionate Uprisings: Iran’s Sexual Revolution. A former journalist turned academic, she has written for Ms. Magazine, Foreign Affairs, The Conversation, The Huffington Post, Jaddaliyya, and The Los Angeles Times Magazine.

Extracted from Hyphen, by Pardis Mahdavi, which will be published in Bloomsbury’s Object Lessons series on June 3.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3fsfef3

Comments

Post a Comment