John Vincler’s column Brush Strokes examines what is it that we can find in paintings in our increasingly digital world.

El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos), The Vision of Saint John, ca. 1608–14, oil on canvas, 87 1/2 x 76″. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Public domain.

I will remember 2020 not as a year of looking but as a year of listening. For months as the pandemic overtook New York, ambulance sirens sounded at all hours in strange choruses. When the sound of the sirens would break occasionally or fade into the distance after dawn, it was replaced not by eerie silence but by birdsong: the shrieks of the blue jays, the playful cheeps of the sparrows in the bushes, the eeks, chirps, and oddly varied sounds of the grackles everywhere. I wondered then, Were these sounds always here, and it was we who were made quiet? I rarely left my neighborhood of Ditmas Park, in Brooklyn, except to take my partner, Kate, pregnant with our second child, to appointments at the Manhattan hospital complex that was itself a hive of sirens that grew louder each time we approached. In my memory the sirens and birdsong were followed by police helicopters seemingly always overhead, as the city erupted in Black Lives Matter protests and the violent police response that only ensured they should continue. The helicopters loomed in the skies above as I ran circles over the same patch of weeds in the small plot of our shared backyard, playing a game my four-year-old daughter, Leo, calls “dinosaur chase” (she is the dinosaur, I am her lunch). Half the year was marked by interrupted sleep—first the constant fireworks at all hours of the night and then, by the end of the summer, the squawking and cooing of the baby, unaware of the distinction between day and night. As I write this, collecting a year, it is spring again. The neighborhood seems to be returning to some approximation of the old sounds from before. That is, if we can recall the way it used to sound. Even the old sounds are heard differently now. With my daughter in her mud boots, bird book and binoculars in hand, as the baby sleeps at home on Kate, we begin each day our circuit. Leo collects sticks, rocks, and seed pods, stomps in puddles, and pauses to track blue jays in a tree, following their noisy stutter.

This past October, I had my temperature taken outside of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. After seeing the line that snaked out for what seemed like a mile, I immediately wanted to leave. There were a number of reasons I felt so jittery. I was concerned about the ethics of visiting at all, of the labor of the museum worker, a role I had once played, having to now be exposed regularly as they held the thermometer to our foreheads, even the baby’s. Also, I was worried that maybe Leo had gone feral for the better part of the year, no longer spending her days on the college campuses where her parents taught or in the museums and galleries we frequented. I tried to keep her standing on her yellow dot, as she agitated to dart off and play in the fountain. The idea was to make a pilgrimage to experience a shard of the abruptly abbreviated Gerhard Richter show that had closed nearly as soon as it opened in March 2020. My distrust of the press-preview experience of art had left me waiting to see the exhibition among a crowd, and by then it was becoming clear that it was unwise to gather in crowds at all. In the months afterward Manhattan became a place over the river, its galleries and museums suddenly impossibly far away.

As I waited in line that October, I carried the experience of the previous months with me. I was hopeful, I think, that this set of works—in which an artist many would claim as the greatest living painter addresses the greatest catastrophe of the twentieth century—was just what I needed to jolt me back to attention, to help me rediscover the possibility of painting as a means of speaking to moments of crisis. I had previously caught Richter’s 2012 retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, a show that displayed his inimitable virtuosity across a range of styles and mediums, from painting to sculpture, even if to me his work often seemed cool, lacking in humanism or—what I recorded then in my notebook—soul, but for a few exceptions found mostly in portraits of his family or intimates. Completed by Richter in 2014, the four canvases at the Met that make up “the Birkenau series” were created in response to photographs secreted out of Auschwitz-Birkenau in August 1944. After studying the paintings, I turned to look at reproductions of the much more affecting source images. The pictures, which document the process of mass murder in the gas chambers of Nazi concentration camps, were taken by a member of the Sonderkommando, a group of mainly Jewish prisoners forced to help carry out the atrocities, as the caption explained. The high-contrast black-and-white photos are themselves almost abstractions, with the black of a window frame bracketing much of the images and a forest at the center, the figures barely perceptible before and below the immensity of the trees. In the gallery, the photographs were situated so they remained out of view when one looked at the paintings, and vice versa. As I turned from the photos to the four large canvases in black, white, gray, green, silver, and red, I noted that the paintings themselves revealed essentially nothing of the source images within their smeared and scored surfaces of chaotic, vaguely grid-like constructions. I scanned the paintings, and then I backed away to take them in again at a distance, as a totality. I struggled to find a generous reading of this accrual of marks and pigments. I felt an unsettling empty feeling alone there in the gallery. Standing before these paintings, I felt no sense of awe or stirring of emotion beyond the thinking I had brought into the gallery in anticipation. I thought to myself, or perhaps I even said it out loud: So he paints over atrocity—is that what I’m looking at here? These paintings added nothing by way of insight and seemed only to undercut the power and witness of the original photos. Why was I even here? Why was I looking for solace in paintings? We were still in the midst of a plague. It felt foolish to be standing amid the opulence of the Met.

Maybe the problem was mine. Could I even look at art again? Or rather, would it ever be the same for me after the events of the past year? But with attention, art never is the same. Art occupies a tenuous middle distance between one’s present state (and accrued personal history) and the current cultural moment (as a point in time within history). Each artwork must present itself between these ever-shifting poles. These Richter paintings seemed like a failed attempt to extend his squeegee technique, used in his grand late abstractions, into the space of profound meaning through historical association. Maybe the failure of the Richter paintings is the point. Could any attempt to paint the events glimpsed in the source photographs succeed, and if so, what would that mean? Wouldn’t any such attempt result essentially in painting over atrocity? But these oversize canvases were neither a monument memorializing the victims nor an attempt at reckoning with the nationalist violence behind the atrocity. Perhaps what drew me to the Met wasn’t that I was seeking an experience of art. Maybe it was that I had been missing the city, of which the Met is an essential part. But what I had never previously considered, at least so viscerally, was how much the Met as an institution obliterates the lived reality of New York. While in other times this rendered the Met as a haven or an escape for New Yorkers, in this moment I found it alienating.

Having seen the set of pictures that served as the ostensible reason for my trip, I wandered unintentionally to the relocated and rehung El Greco paintings, with their familiar melancholic faces and elongated hands, and the unparalleled expressive monochromes of the sinuous fabrics enfolding light into clothing. Here I saw them in their new location for the first time.

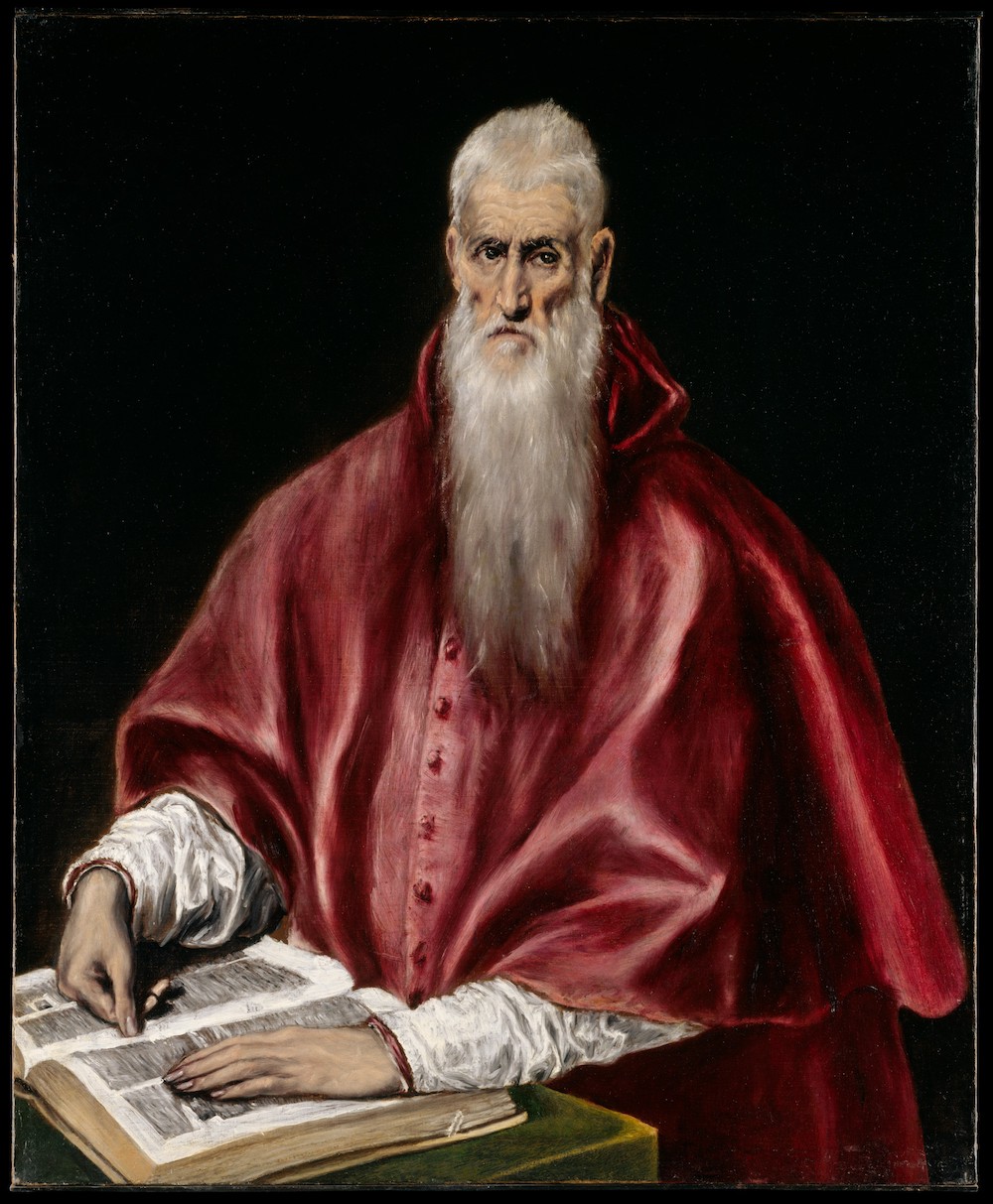

El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos), Saint Jerome as Scholar, ca. 1610, oil on canvas, 42 1/2 x 35 1/8″. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Public domain.

His portrait of Saint Jerome “as scholar” met my gaze, the subject in red robes with a cloak-like mantle from which luminous, wrinkled white sleeves emerge, his hands in a book, his right thumb signaling some illegible passage. Saint Jerome is an icon of the solitary work of the scholar, writer, or translator, and the possibility of this work being contemplative, meditative, and meticulous. I contrasted this to El Greco’s View of Toledo, in which the city emerges from the landscape underneath a sky threatening to storm, the clouds unable to suppress the light filtering through their diaphanous layers, illuminating everything. What generations of humankind had built in the depicted city remains dwarfed by nature’s mercurial powers. These paintings reassured me like an old friend who could understand and tolerate me in a sour mood through the camaraderie of shared silence.

El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos), View of Toledo, ca. 1599–1600, oil on canvas, 47 3/4 x 42 3/4″. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Public domain.

As I met up with the rest of my family, left the museum, and headed into Central Park, the sounds of traffic quickly gave way to the sounds of birds. I thought of Louise Lawler’s audio work “Birdcalls” (1972/1981), which plays in the garden space of the Dia Beacon museum a few hours north by train along the Hudson. The piece plays amid the chatter of the real birds in the garden, performing a sort of audio camouflage as Lawler renders the names of famous male artists into bird calls. “Rick TUHR, rick TUHR,” she cries—one of about thirty names she cycles through in the seven-minute audio loop. I called this out to myself in my head, immediately easing my mood, there behind the Met, listening in a crowded park quiet but for the birds. Even if Lawler’s work existed there only in my memory, it was as if I were hearing and comprehending it for the first time, understanding with greater depth how she both sent up the limits and undercut the myth of the great painter.

As I walked through the park, I realized that the room of rehung El Greco paintings didn’t include The Vision of Saint John, a painting perhaps best known for being a model and inspiration for Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon some three hundred years later. I always see in its orgiastic scene the dawning of a mode of abstract painting, a freedom emerging like revelation as the cloth on the blue figure at left is undone in red, yellow, green, and white, naked figures rejoicing before these dynamic blocks of color. I thought of when the pandemic would be over, when we could take off our masks and be with one another. And I thought of how museums and paintings can and cannot help us to consider what this collective freedom might look like. I listened to the birds.

John Vincler is a writer and visual artist who has worked for a decade as a rare-book librarian. He is editor for visual culture at Music & Literature and is at work on a book-length project about cloth as subject and medium in art.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3uug7YK

Comments

Post a Comment