William Hilton, John Keats (detail), ca. 1822, oil on canvas, 30 x 25″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Poets can be divided into two groups: those who dutifully tortured “When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be” in secondary school (POET = WORRIED ABOUT DYING scrawled unhelpfully in the margins) without ever giving its author a second thought, and those for whom Keats serves as spiritual teacher. To his followers, Keats is a poet’s poet, is the poet’s poet, a writer whose brief span compressed all the love, pain, and existential uncertainty of a lifetime, which the finest of his fifty-four published poems animate. He believed pain and trouble were their own education, “school[ing] an intelligence to make it a soul.” His was a rare gift, and yet his best poems weren’t earned without effort; early examples are uneven and clumsy, and for that perseverance and learning by shrewd emulation, we admire him all the more. His death at twenty-five trapped that quiddity in amber.

“When I have fears that I may cease to be”—and then he did; he died young, corroborating that fear, poised and brave in his final moments, and leaving the rest of us neurotic types (what sort of reasonable person isn’t hung up on the terror of premature death?) wringing our hands, staring into the middle distance. In this way, Keats confirms every poet’s greatest anxiety—that our fears, in truth, are sometimes justified, and that our clever poems may know more than we do.

These, of course, are my own ramblings on a figure whose life I found myself drawn to only once I had outlived him. Each year now brings me paradoxically closer and farther from Keats.

Andrew Motion’s biography of the poet is fantastically scholarly and accessible, a term that’s been so overused to mean almost nothing. What I mean is this: on a Sunday in ninety-degree heat, you can lift the tome in your withered state, flip to a chapter at random, and find Motion guiding you with energy and intelligence, and a true sense of partaking in the marvelousness of Keats with you. Motion is wonderfully clear and direct while still making his mark on the prose at every turn, as on our understanding of the dimensions and shape of Keats’s life through his well-considered interest in the poet’s social and political circumstances. His description of Keats’s dying moments is quietly gripping, worthy of a season finale of one of the dozen medical dramas that multiply like invasive species across American television, and yet the book goes on another twenty pages, making such partings bearable. Life goes on, even when major stars extinguish. In Keats’s case, that extinguishing served as a spark, with each subsequent generation of poets holding vigil. —Maya C. Popa

When I came across theMIND’s album Don’t Let It Go to Your Head, I had just met a deadline. I mean, I met the deadline at 3 A.M., but it still counts. Instead of going to sleep, I started listening. When I finished the album for the first time, I sat up in bed, took out my headphones, and thought, Damn—now I gotta rewrite everything. There was something about the way he observed doubt—saying everything I meant to say, but better—that not only reminded me songs are probably the one thing I’ve ever truly loved in my life, but these songs in particular really allowed me to consider the advice on the intro:

Stop.

You’re overthinking it.

Continue.

Which is probably why I ended up staying awake until nighttime came back around again.

A lot of what I was hearing mirrored what I was feeling about myself throughout the process of nitpicking at words, “[hoping] this honesty saves us.” You really gotta read these lyrics, man. “Atlas Complex”? Broke me. “Sea”? Blessed me. “Craig”? Just @ me. Bars on bars on bars on soul on heart on God. It’s like although the content is heavy in an interior way, you can still clean ya house to it. No skips. Spotless sweep. To say I’m obsessed is an understatement. —Kendra Allen

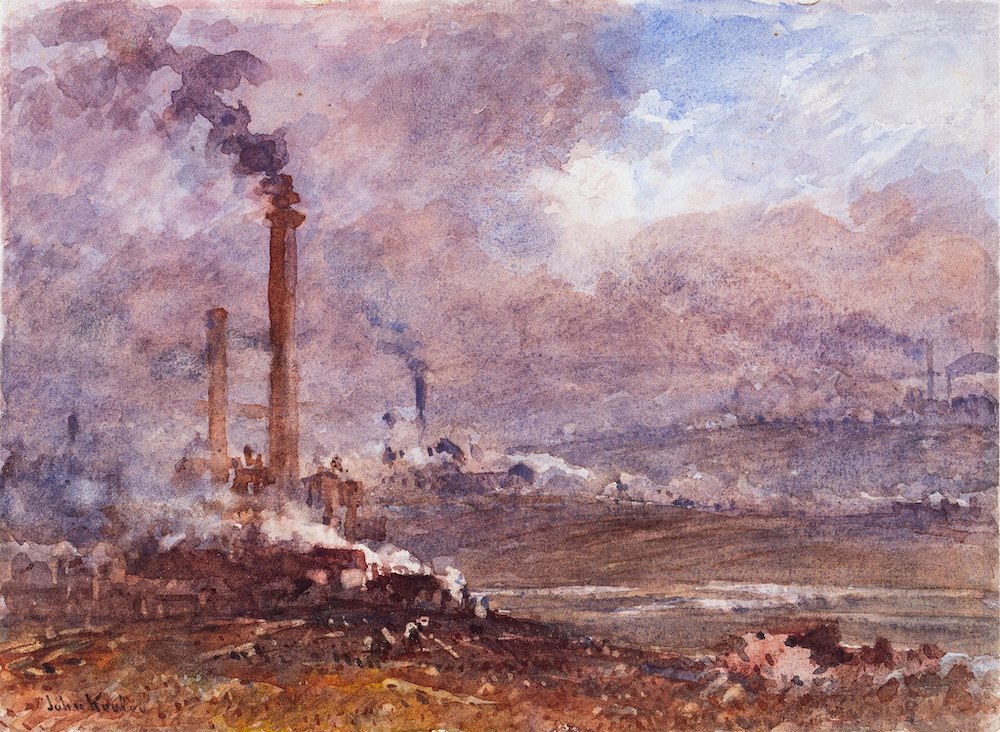

John Keeley, Among the Coal Pits, Staffordshire, n.d., watercolor, 9 1/2 x 9″. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Maybe because lockdown is a little like being buried alive in your own life, I’ve been thinking about mines and mining and miners lately. Here are three sources on what it’s like to be a miner, the art and craft and deadliness and language and silence of it, and who cares.

Brassed Off, a movie about the troubles faced by a colliery brass band upon the closure of their pit, directed by Mark Herman, 1996.

“Nottingham and the Mining Countryside,” an essay by D. H. Lawrence about his father, who was a miner, and about his own childhood in a mining town of Derbyshire, available in Geoff Dyer’s The Bad Side of Books: Selected Essays of D.H. Lawrence.

Coal Mountain Elementary, book-length poem by Mark Nowak on miners in West Virginia and in China, and how to teach children about them in an elementary school. —Anne Carson

When I’m feeling down, uninspired and going dead-eyed to the sound of my laptop’s whirring fan, I’ll seek out a live recording of a band that saw me through my nineties adolescence. These videos tend to be of shows from the band’s early years, before they were famous, or at least super famous, the VHS recordings of talents about to break out, transferred and readily available on YouTube. The one I go to most is Nirvana’s November 20, 1989, show at the venue KAPU in Linz, Austria.

By then the band had been around for a couple of years and were touring in support of their just-released album Bleach. In the video, which for some reason has a timestamp of November 21, it’s as if everybody is crammed into a living room, and the band looks like they’re slouching under KAVU’s low ceiling. Weirdly synchronous with our days, bassist Krist Novolesic is sporting a handkerchief over his face. Chad Channing, the band’s first drummer, sits sleeveless at his kit. Next to him, the band’s “Fudge Packin” T-shirt without the “Fudge Packin” text, or it’s something like the “Fudge Packin” T-shirt anyway, is on display by a TAD shirt. I think Kurt Cobain is playing the Hagstrom II F-200, which, if you want, you can watch him smash seven days later at the end of a show in Italy.

The sounds of these songs are obviously way different from the album versions, or even the live versions played during shows post–In Utero. They’re way more intimate and way more representative of who these musicians were as regular aspiring artists, not just budding rock stars. Instead of the dramatic, sudden openings of later shows, there’s a couple minutes of them milling about and tuning their instruments, finding their sound, and then, with nothing more than a couple nods at Channing, Cobain starts “School.” During “Scoff,” Cobain loses his pick and Novoselic just screams into the mic and yells the next verses. Then more tuning, and Novoselic, his cornball self, saying, “It’s great to be here in Australia, but I haven’t seen any kangaroos yet.” Right before the video cuts out, Cobain turns off his amp and says, “Will you buy our T-shirts?”

My chest tightens every time I watch this video. I think it comes from getting to pretend I’m taking part in history, while knowing the greatness and the sadness that lie ahead for the musicians. They have no idea how amazing things are about to get for them. But it will be short lived, and so I’m left with a kind of inspiration that only comes from complete gratitude. —Peyton Burgess

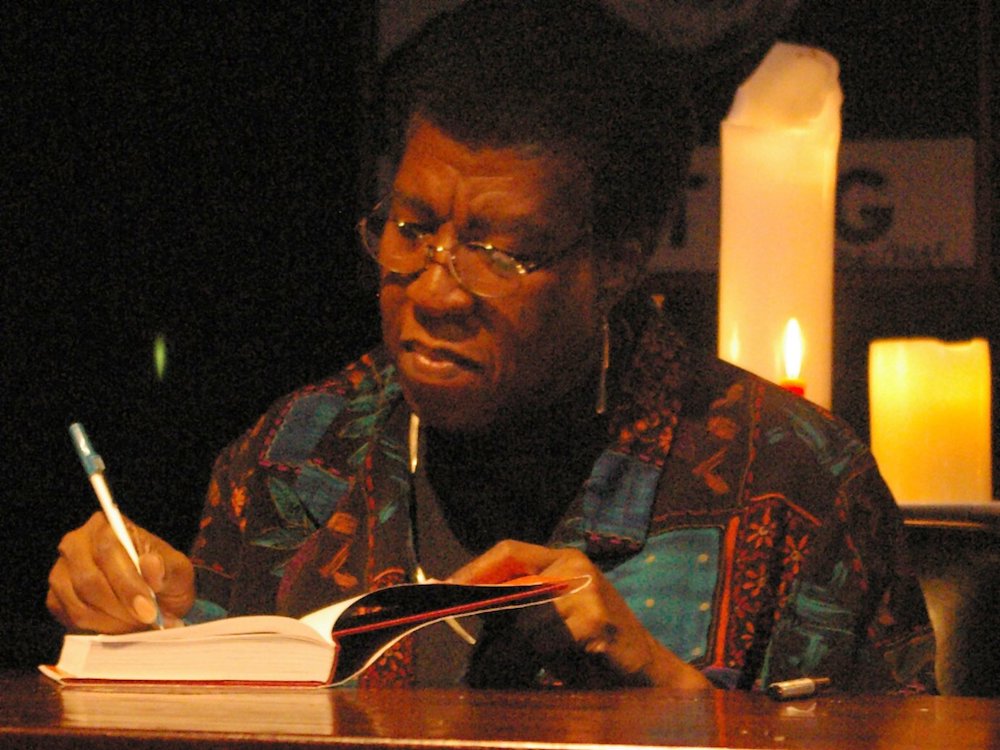

Octavia E. Butler signing a copy of Fledgling, 2005. Photo: Nikolas Coukouma. CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://ift.tt/2jLwzEi), via Wikimedia Commons.

I’m reading Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower for the first time. Is it odd to say, already, that I recommend it? Unlike many of Butler’s other works, this book contains few science fiction elements. The book’s action begins in 2025, in an almost-lawless United States, where climate change and economic crises have degraded government systems to husks. Lauren, our protagonist, lives in a gated community in California, on the wafer-thin line between relative safety and the poverty, crime, and chaos of the surrounding town. Butler imagines a desolate future shaped entirely by America’s own past.

There is a calmness to Lauren, though, as she journals her way through the destruction of everything she loves. In addition to being deeply empathetic, she is also intelligent, focused, and thoughtful. In this stillness, I see Butler’s clarity as a writer, her ability to hold devastating realities about America at arm’s length, to unflinchingly describe their contours on the page.

Early in the book, Lauren writes: “I’m trying to speak—to write—the truth. I’m trying to be clear. I’m not interested in being fancy, or even original. Clarity and truth will be plenty, if I can only achieve them.”

The norm is to recommend books only after one has finished them. But lately, I’ve been thinking less about the satisfaction of checking off a book as “finished.” There is always pressure to keep charging forward, to move on to the next thing. I’m thinking a lot more about the immersive experience of reading slowly, of being present in the narrative moment.

Amid the pressure to resume pre-COVID life without looking back, I find solace in this slowness, in losing myself in Butler’s study of America, which is as much about our past as it is a warning about our future. —Yohanca Delgado

The limits of horror are getting tested lately. As I watched the Swedish film Border, directed by Ali Abbasi, I was reminded of horror’s fundamental philosophical question: What is human? This question comes to life the moment something inhuman or monstrous invades normalcy. In Border, the monster has already invaded in the form of Tina, an agent whose job is to detect smugglers for the Swedish Customs Service.

The territorial borders of Sweden are not the only boundary Tina is tasked with protecting in this old-growth horror film. Tina, whose every facial feature is subsumed to the operations of her nose, does not fully present as human. Her ability to detect contraband by smelling emotions of guilt on the human carrier makes her invaluable to the customs service. Tina is without a doubt at the border of the animal and human realms. She is visited nightly by the woodland creatures around her house, and a moose seems to find her company of endless good use.

Abbasi sets his story in the realm of fairy tale, where trolls and changelings nibble on maggots at the edges of forests and bassinets. When a man named Vore passes through customs, Tina’s affinity to him overrides her duty as boundary keeper. She will learn from Vore that she is not human. Abbasi employs allegory to test the boundaries of gender by reversing the secondary sex characteristics of the main characters. Border also explores the frail status of the foreigner in Sweden. This seems fair game in a country where children from refugee families faced with deportation have been known to fall asleep for years.

Tina also learns from Vore of the crimes committed against her kind. However, Vore is tainted by his unbound vengeance against humans, and Tina will have to choose between the ruthless morals of her own kind and those of her abductors, humans.

Border reminds us that we, humans, have an innate moral sense that directs us toward ethical conduct. Yet, at the very moment that Border delivers an affirming yes through the ethical actions of its protagonist, I was struck by how outdated that question—What is human?—has become. Though we, humans, may know the difference between right and wrong, this does little to dismantle the model of planetary depletion and extraction we benefit from. We are stewards of our destruction.

Tina’s affinity with the animal world seems the most evolved stance in Abbasi’s Border. Perhaps the question of the horror film is no longer what is human and what is inhuman, but whether there is enough animal left in the human to save us. —Mary Kuryla

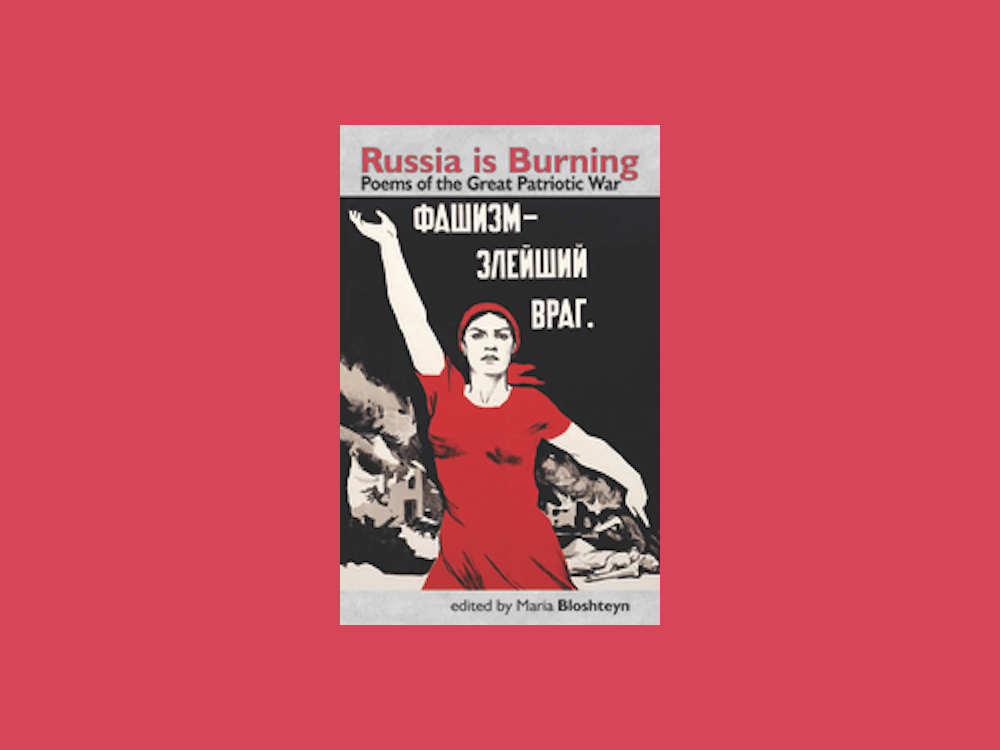

In “Sventa,” the essay I translated for the current issue, Maxim Osipov returns to Lithuania after a long absence and finds the landscape he knew in his youth irrevocably altered. To try to make sense of the changes and to absorb their impact, he relies, as Russian speakers often do, on poems. These are the lines that come to his aid: “A house stood here. […] / And now a bird goes flying through / the empty space that was a window.” They belong to Ivan Elagin (1918–1987), one of many Russian authors whose lives were upended by World War II. Together with his wife and fellow poet, Olga Anstei, he stayed in Kyiv under Nazi occupation; the couple left with the retreating Germans in 1943, were placed in a DP camp, lost an infant to pneumonia, and, in 1950, immigrated to the United States, where they soon divorced. In emigration, Elagin became a major poet, whose poignant, self-interrogating verse reflects what Edward Said called the “double perspective” of the exile, who “sees things both in terms of what has been left behind and what is actual here and now.” I’ve translated a number of Elagin’s lyrics (here, here, and here), but his unflinching “double perspective” is most vividly captured in the long poem “Fadeout,” which Maria Bloshteyn has translated and included in her extraordinary anthology Russia Is Burning: Poems of the Great Patriotic War. In the poem, Elagin, who served as an ambulance driver under occupation, suffers the fresh trauma of a car wreck outside Chicago, which dredges up the old trauma of transporting a dying soldier to hospital under heavy bombardment: “We drove out of Chicago. / The skyscrapers behind us / were covered up by smoke. / A moment is like gravity, / its pull is indestructible, / it stays within us locked.” Russia Is Burning gathers the work of nearly a hundred poets and offers a bravely, unprecedentedly nuanced portrait of the Russian wartime experience and its aftermath. I’ve been reading it throughout this past year, and each page reminds me that no tragedy leaves its survivors unmarked. —Boris Dralyuk

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3hZVBgj

Comments

Post a Comment