Just as there are an infinite number of stories to be told, there are an infinite number of ways to tell a story. Take Hazel Jane Plante’s Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian) as case in point. When the narrator’s best friend dies, she decides to write an encyclopedia about her friend’s favorite television show. While Plante’s novel takes the form of an A-to-Z guide to the fictional one-season TV series Little Blue, it also tells the story of a queer trans woman mourning the loss of her straight trans best friend, for whom she felt an overwhelming, unrequited love. Through her thorough examination of the show, the narrator creates a beautiful, holistic homage to Vivian’s life. At the end of Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian), I found myself in awe of the book’s author. Not only has Plante imagined an incredibly complex TV show from scratch, she’s written an entire encyclopedia about said show, and somehow told a deeply heartfelt story of mourning, love, and friendship in the process. —Mira Braneck

It is a cliché to observe that the more things change, the more they stay the same, but clichés are clichés for a reason, and across time, space, and history, the squabbles and dilemmas of leftist political movements seem to repeat themselves over and over. The criticisms that the Egyptian feminist, communist, and leader of the seventies student movement Arwa Salih lodges against her generation in the 1996 book The Stillborn: Notes of a Woman from the Student-Movement Generation in Egypt (translated from the Arabic by Samah Selim) are at once particular to her country and moment and also familiar outside their context. A supposedly worker-led movement, she observes, quickly becomes dominated by the bourgeois intellectual class, a vanguardism that functions as “the first step on the road to disengagement from the real world … One of the coarsest forms the hierarchy took was the division between ‘authors’ and everyone else—the drudges who did the heavy lifting and who were also the most likely to be captured by the police.” One chapter, “The Intellectual in Love,” is fiercely critical of the sexism displayed by ostensibly radical men: “Our friend considers it his right to exploit her. His logic is that since she’s accepted exploitation, she deserves it.” Brief in pages but deep in scope, The Stillborn is a fascinating analysis of both revolutionary politics as a whole and the failures of the Egyptian student movement in particular. —Rhian Sasseen

Even in the most socially agreeable of circumstances, it can be hard to make genuine connections with others. Considering our recent trend toward a distraction-hungry, internet-fueled, dopamine-overloaded dystopia and all the longstanding anxieties that come with the uniquely human awareness of a finite existence, it’s a wonder that any of us manage to make friends at all. The cartoonist Will McPhail investigates this very wonder with his debut graphic novel, In., which follows a burgeoning illustrator named Nick as he struggles to connect with those around him, not quite finding a meaningful enough balance between what is considered socially palatable and what he actually feels, adrift between the performative and the authentic. As a medium, the graphic novel is beautifully suited to depicting such concerns, and McPhail’s art style—reminiscent of his work in The New Yorker—is minimal, direct, and as emotionally dense as any work of contemporary poetry. The spare use of color against a largely monochrome palette is particularly effective, not just in illustrating emotional changes but in conveying them—the vibrant fantasies of Nick’s inner world are as arresting, enveloping, and ultimately fleeting for the reader as they are for the protagonist. In. is a sharply observed, funny, and achingly poignant examination of a subject widely understood yet rarely described, rendered subtle and playful, and made wonderfully new. —Christopher Notarnicola

Showtunes is a great Lambchop record, and that’s a high bar for a band whose output almost always lands somewhere in that range between really good and incredible. Songwriter and bandleader Kurt Wagner has been, over the past several LPs, edging toward a new sort of tweaky electronic twang, autotuning and otherwise manipulating his soft, gravelly voice while also using loops, programmed drums, synths, and other effects that don’t usually appear in alternative country music. I still haven’t fallen in love with the band’s previous album of original material, This (Is What I Wanted to Tell You), on which Wagner’s inimitable songwriting voice feels lost in a storm of moody electronics; it feels like he hadn’t yet found a way to integrate these seemingly competing impulses. But barely two years and one pandemic later, he has. Showtunes is a strange and comforting album: quiet, melancholy, but not without hope and consolation. Melody is at the forefront, as are the trappings of Lambchop’s sound—fingerpicked acoustic guitar; long, loping musical phrases; gorgeous, winding vocals; artfully arranged horns—but subtle manipulations abound. It all feels of a piece, a sweet way of welcoming a new season. —Craig Morgan Teicher

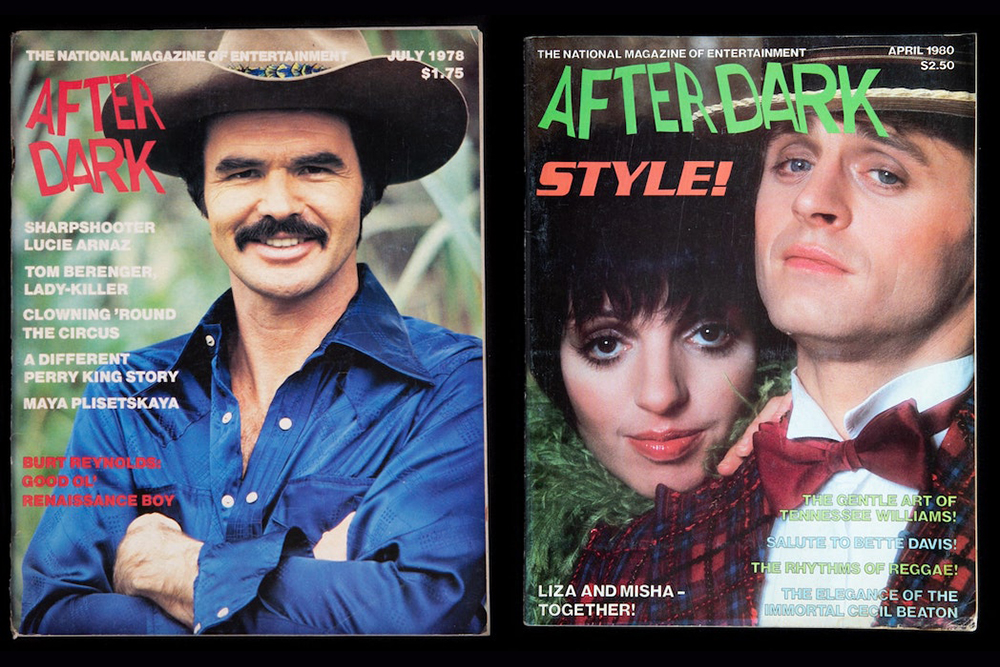

A few weekends ago, St. Mark’s was nicely crammed with young folks eyeing zines and small-press wares, taunting dogs with skateboards and one another with skin. Among the hiply imperfect, inclusive offerings was a magazine polished to a high shine. After Dark was a nightlife and culture periodical produced through the seventies by Danad, then publisher of Dance Magazine. Though officially created to cover dance and city culture, After Dark was gay as the day is long. Hiding in plain sight are letters to the editor requesting further photographs of a model described as “body beautiful” (they were furnished), advertisements for Fire Island bars and NYC baths, celebrations of the nude male form, and lots of purveyors of caftans. Winking interviews with Robert Redford and Burt Reynolds share a binding with campy fashion editorials and spreads of ballet dancers au naturel. It is lovely and light and sexy; if you are thinking the magazine may have faded in the eighties, partly under criticism of a lack of political heft or inclusive gaze, you’d be right. After Dark remains, however, a beautifully shot portrait of a moment. Left Bank Books has lovingly assembled a collection of After Dark issues, many of which are for sale and some of which will be on display in the storefront window through July 5. —Julia Berick

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3di8tuO

Comments

Post a Comment