John Vincler’s column Brush Strokes examines what is it that we can find in paintings in our increasingly digital world.

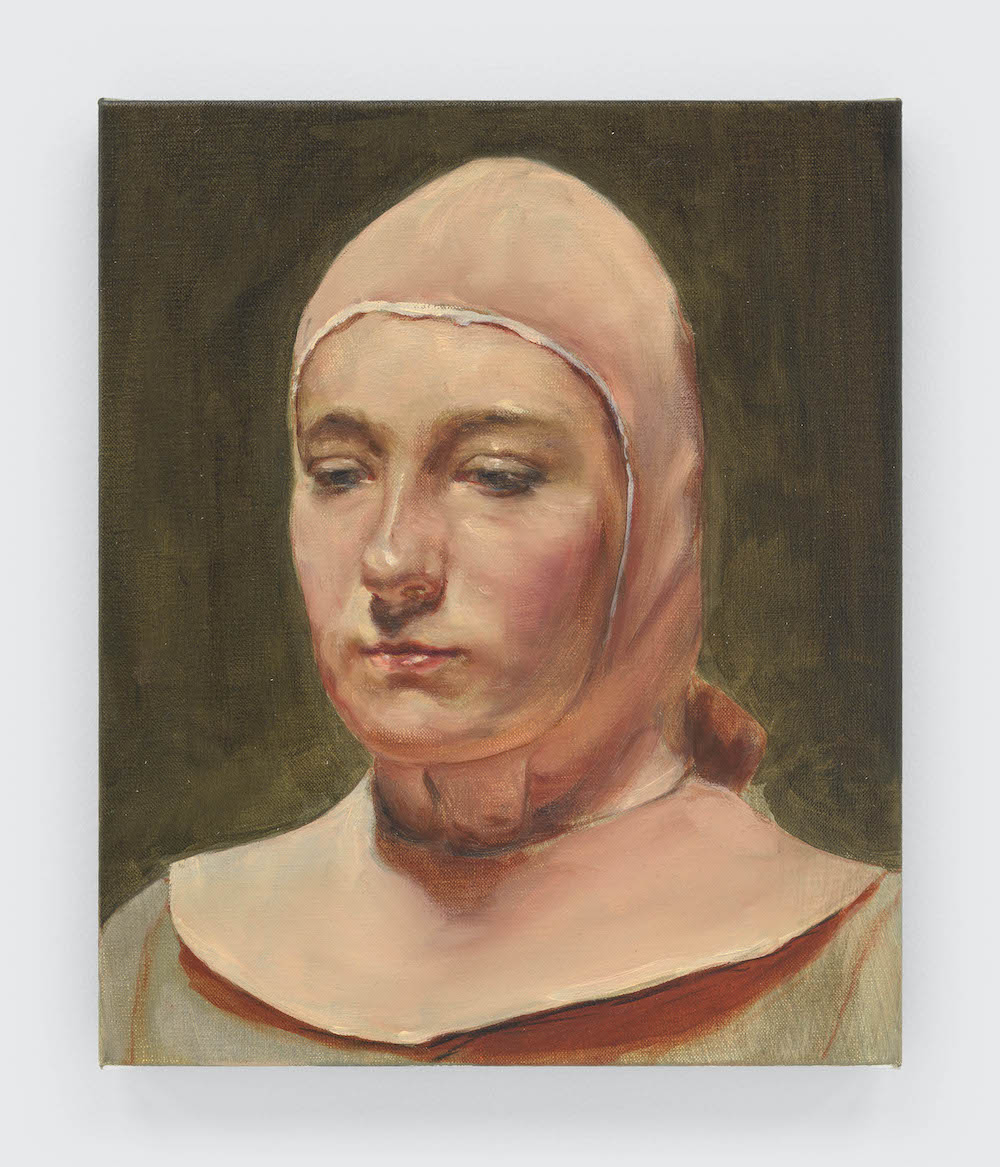

Michaël Borremans, Study for Bird, 2020. © Michaël Borremans. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner.

I didn’t understand how much I needed to look at the faces of others until I drove into Manhattan this past December to stare into a stranger’s unmasked face on my birthday. The sole reason for this trip was the stranger’s face—a portrait by Michaël Borremans, an artist I had taken to describing for nearly a decade as my favorite painter whose work I had never seen in person.

I knew Borremans’s work mostly from the giant monographs and exhibition catalogs on his work I’d check out from the Mid-Manhattan Branch of the New York Public Library several years ago while I was working as a rare-book librarian a few blocks south at the Morgan Library & Museum. I’d lug these giant books from one library to another and then home in my backpack on the train from Midtown back to Brooklyn, renewing them over and over until they could be renewed no longer, sometimes requesting them again immediately, repeating the cycle. These paintings, or at least their reproductions, had a special resonance for me then. In the Morgan’s reading room, I routinely looked at the miniatures painted in the medieval manuscripts requested mostly by visiting academics. And when I would reshelve the printed books housed in J.P. Morgan’s former study in the old library, I’d always take a moment to look upon Hans Memling’s panel painting Portrait of a Man with a Pink.

This day job rhythm fueled an almost ambient thinking about the relationship between medieval manuscript illumination and what I still think of as, to use the art historian Erwin Panofsky’s now-antiquated phrase for work created during the transition from late medieval to early modern painting, “early Netherlandish” panel painting. In Borremans’s paintings, I saw a contemporary inheritance of this dawning moment. Borremans lives and works in Ghent, home to the brothers Hubert and Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece. Begun in the 1420s and completed in 1432 (probably primarily by Jan after Hubert’s death and following his initial design), this landmark historical artwork was one of the first paintings to use oil paint and a series of transparent glazes to create radical effects with light. Ghent is some twenty-five miles from Bruges, where Memling was the leading painter in the second half of the fifteenth century. In Memling’s work, the uncanny renderings of skin tones alive with light and paired with lushly textural treatments of often brocaded and jeweled clothing captivated me with their detail. Skin and clothing, faces and postures are also essential elements of Borremans’s work. As I pored over the reproductions of his paintings in those giant library books, I sensed a genealogical connection across generations to his geographically proximate forebears. This is not to say that his paintings are antiquarian-seeming curios; rather, he takes on figuration as if in a sort of dare, rendering his subjects with a freighted ambiguity. In Borremans’s work, it is as if the Catholicism of the early Netherlandish painters’ cathedral setting has fallen into ruin and been replaced with a desolate absurdist stage set. The people in his portraits often seem as if they are playing a role in some mysterious production, adding a layered tension to an existential question they ask of both themselves and the viewer: What am I doing here?

On that blustery Saturday in December, I put on my mask, left the shelter of my car parked on the mostly empty streets, and ran across the pavement through the freezing rain to the David Zwirner Gallery, where my partner, Kate, had booked me a timed socially distanced appointment for my birthday. The trip to Manhattan to see the single Borremans was my second attempt to reengage with looking at paintings after the onset of the pandemic. I appeared to be the only visitor in the gallery that morning. In the large skylighted room farthest from the entrance, I was able to gaze upon the smallish canvas I had come to see. Measuring less than twelve by fifteen inches tall, Study for Bird is an intimate work painted by Borremans during the pandemic. In scale it echoes that Memling I spent years looking at in the Morgan. Returning to the Zwirner gallery was entering a familiar but seemingly altered space, not abandoned but haunted by the too-real fullness of the year’s history. It was a rare gift of solitude. Kate stayed with our baby still asleep in the car, as my eldest finished drawing on a birthday card. I had the gallery to myself, except for two attendants, one at the front desk and another in the gallery itself. They had pointed me in the right direction to see my first Borremans in the flesh.

What did I see? A human face, a stranger’s, unmasked. Settled, contemplative, resolute, yet melancholic. An inward look. Softly femme. Slight makeup, most noticeably blush high on the cheeks. Or perhaps they were pink with exertion. A touch of gloss on the lip, which caught the light, but so did the bridge of the nose and the peak of the left brow. A ballet dancer, a player onstage? Or maybe, as the hooded costume suggests, a pilot or a fencer. The collar floating, otherworldly, tracing a circle below the neck.

The problem here seeking a solution by the painter is the face the hood encloses, part transcribed realism and part affective invention. The figure is set before a dark ground; the darkness is drafted, filled as an afterthought. There’s something cursory, vague about this darkness, which serves to hold the figure in a field of contrasting tone and then get out of the way, to be the shadow uninvolved in the otherwise complex play of light across the face and its surrounding costume. The bit of darkness in the space behind the neck creates an area where the image peels away or falls apart, but just for a flash, a blip, just for a moment. (Maybe this is where long hair is secreting out the back of the hood.) This ambiguous bit of fabric or hair behind the head flares slightly up from the body and creates an area of just enough strangeness to reveal the plasticity and thus the inventiveness of the painting itself, as if the painting were paused just before the stroke of completion.

The attendant, maybe curious that I seemed principally interested in the Borremans painting, mentioned that it related closely to another Borremans painting, titled The Pilot, that was concurrently being shown at the Zeno X Gallery in Antwerp. I had seen The Pilot online along with paintings of rockets and people dressed in rocket-like costumes. Of Study for Bird, she said the figure looks to be playing a pilot, “like Amelia Earhart.” It felt awkward and exhilarating having a conversation with a stranger about painting, attempting to remember how to do that, keeping our distance, wearing our masks.

Thinking back on that moment before the painting in the gallery, I now realize I would usually have taken the subway. I have only just started taking the train again, which has reminded me that the experience of New York usually is an experience of a sea of innumerable faces. Taking the subway means daily having at least one person’s face across the aisle and many faces in your line of sight. You can’t help but study the concentrated face of a reader, the elsewhereness of a daydreamer, the sadness here, the exhaustion there, the twitchy concentration of a game player, the open face of the tourist, and even the practiced but not quite impervious shell of the city dweller, lightly armored in sunglasses or headphones. In staring at the face in Borremans’s portrait, I wasn’t left thinking about the history of early Netherlandish panel painting. I was instead reminded of the experience of moving through a city, the mix of intimacy and alienation that comes from incessant, packed proximity with strangers. It was okay to stare there in the gallery, to contemplate the dignity and complexity of this subject, with the strange costume, the visage part mask and part portal, suggesting something as awesome and truly unknowable as an individual person. Isn’t this a paradox, to be made to remember the faces of strangers?

John Vincler is a writer and visual artist who has worked for a decade as a rare-book librarian. He is editor for visual culture at Music & Literature and is at work on a book-length project about cloth as subject and medium in art.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3ldTV4u

Comments

Post a Comment