Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re redrafting, rewriting, and revising. Read on for Kenzaburo Oe’s Art of Fiction interview, Sigrid Nunez’s “The Blind,” Aaron Bulman’s poem “The Revision,” and Lydia Davis’s essay “Revising One Sentence.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. Or, choose our new summer bundle and purchase a year’s worth of The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for $99 (that’s $50 in savings!).

Kenzaburo Oe, The Art of Fiction No. 195

Issue no. 183 (Winter 2007)

INTERVIEWER

Many writers are obsessive about working in solitude, but the narrators in your books—who are writers—write and read while lying on the couch in the living room. Do you work amid your family?

OE

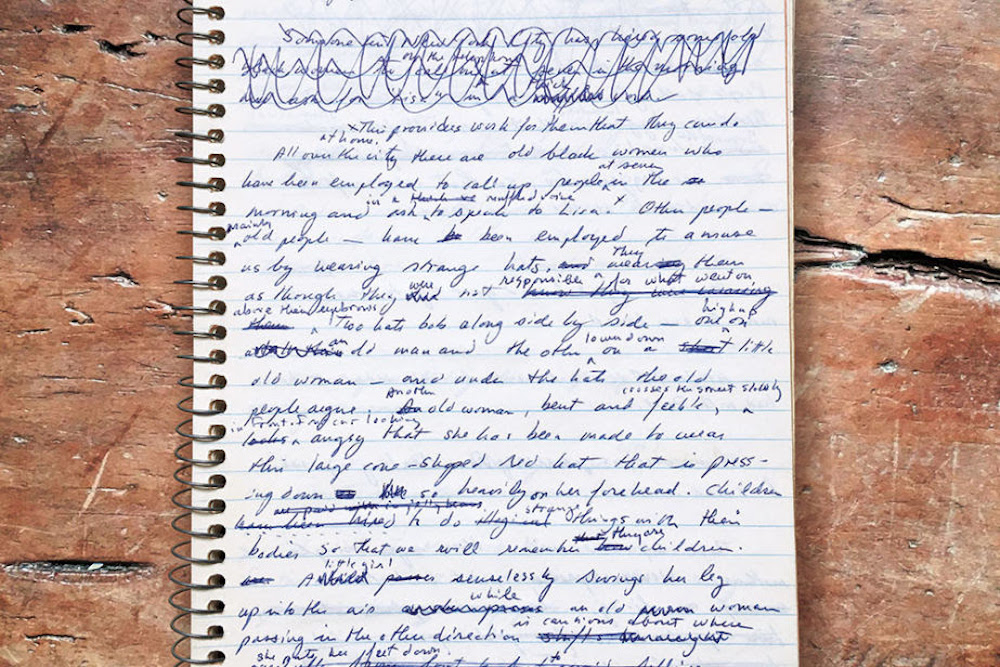

I don’t need to be solitary to work. When I am writing novels and reading, I do not need to separate myself or be away from my family. Usually I work in my living room while Hikari listens to music. I can work with Hikari and my wife present because I revise many times. The novel is always incomplete, and I know I will revise it completely. When I’m writing the first draft I don’t have to write it by myself. When I’m revising, I already have a relationship with the text so I don’t have to be alone.

I have a study on the second floor, but it’s rare that I work there. The only time I work in there is when I’m finishing up a novel and need to concentrate—which is a nuisance to others.

The Blind

By Sigrid Nunez

Issue no. 222 (Fall 2017)

There are things I’d like to know, too. For example, why, when these two girls want to talk, do they keep getting into their cars and driving to each other’s houses? Why do they never use their phones, not even to text to find out first if the other one is home? Why do they not know things about each other that they could easily have learned from Facebook?

It is one of the great bafflements of student fiction. I have read that college students can spend up to ten hours a day on social media. But for the people they write about, though also mostly college students, the Internet barely exists.

“Cell phones do not belong in fiction,” an editor once scolded in the margin of one of my manuscripts, and ever since—more than two decades now—I have wondered at the disconnect between tech-filled life and techless story.

The Revision

By Aaron Bulman

Issue no. 66 (Summer 1976)

I still liked anyothertime,

anyotherplace. which means most

of my life, but it was now,

here, so I felt my life becoming sad.

and I was thinking this

too shall pass into later.

somewherelse. but I was getting sadder …

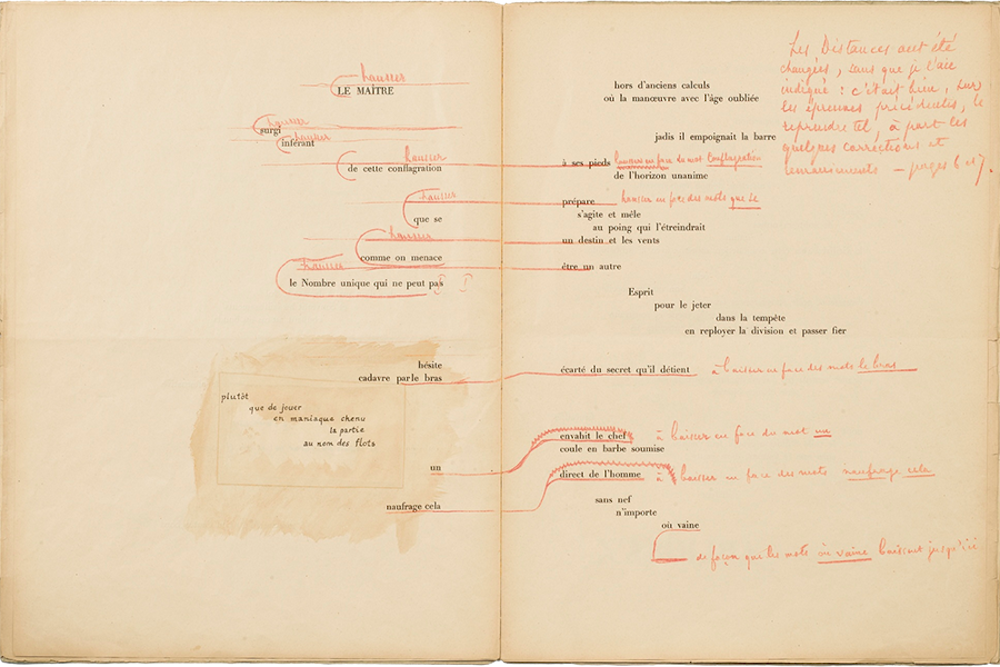

Revising One Sentence

By Lydia Davis

Issue no. 229 (Summer 2019)

I write it down and then immediately revise it. Today I revise this sentence immediately; sometimes I do and sometimes I don’t. Maybe it depends on how interested I am in what I write down, or maybe I don’t revise it if the writing is so simple or brief that it comes out exactly right the first time. Today it isn’t quite right and I must be interested because I revise it: I want it to be exactly right. I will work on it until it is exactly right, whether or not the observation is important and whether or not I think I’ll ever “use” it.

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, choose our new summer bundle and purchase a year’s worth of The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for $99 ($50 off the regular price!).

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3i7NBcM

Comments

Post a Comment