Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re commemorating another year of the best deal in town: our summer subscription offer with The New York Review of Books. For only $99, you’ll receive yearlong subscriptions and complete archive access to both magazines—a 34% savings!

To celebrate, we’re unlocking pieces from the archives of both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books. Read on for Hilton Als’s Art of the Essay interview, paired with his essay “Michael”; Fernanda Melchor’s “They Called Her the Witch,” paired with Emmanuel Ordóñez Angulo’s review of the novel from which it is excerpted, Hurricane Season; and Adrienne Rich’s poem “Architect,” alongside Mark Ford’s essay on two recent collections of Rich’s poetry and essays.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, poems, and works of criticism, why not subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books and read both magazines’ entire archives?

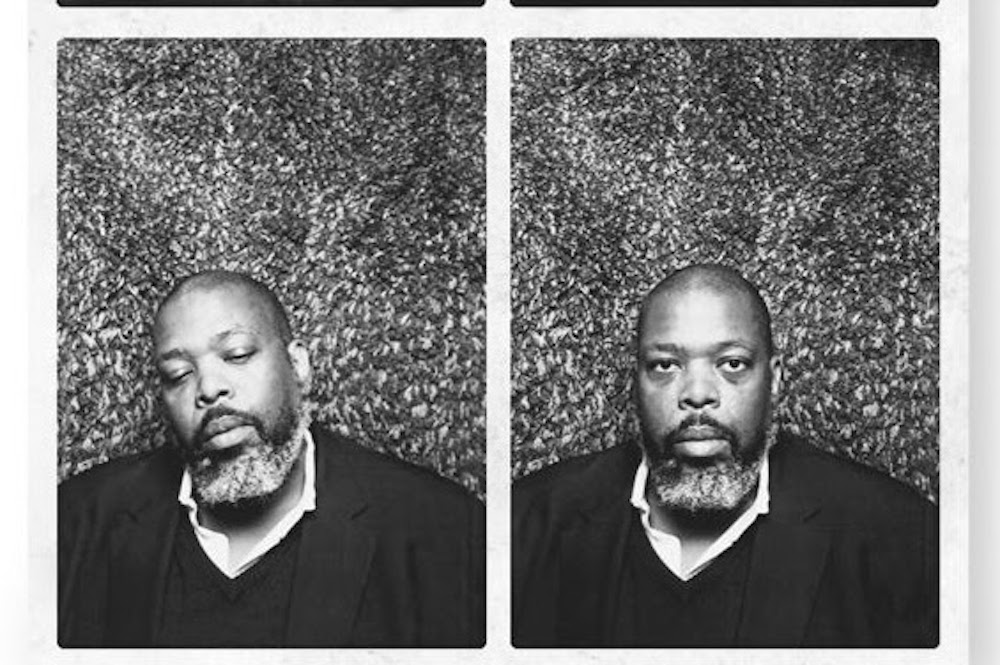

Hilton Als, The Art of the Essay No. 3

The Paris Review, issue no. 225 (Summer 2018)

For me, writing is a way of struggling through the intricacies of an antiempirical sensibility. And there must be words other than fiction and nonfiction. I see fiction not as the construction of an alternate world but as what your imagination gives you from the real world.

Michael

By Hilton Als

The New York Review of Books, August 13, 2009, issue

James Baldwin did not live long enough to see Jackson self-destruct. And the most interesting aspect of his essay in light of Jackson’s death is Baldwin’s identification with Michael Jackson, another black boy who saw fame as power, and both did and did not get out of the ghetto he had been born into, or away from the father who became his greatest subject. But the differences are telling.

They Called Her the Witch

By Fernanda Melchor, translated by Sophie Hughes

The Paris Review, issue no. 231 (Winter 2019)

They called her the Witch, the same as her mother; the Girl Witch when she first started trading in curses and cures, and then, when she wound up alone, the year of the landslide, simply the Witch. If she’d had another name, scrawled on some timeworn, worm-eaten piece of paper maybe, buried at the back of one of those wardrobes that the older crone crammed full of plastic bags and filthy rags, locks of hair, bones, rotten leftovers, if at some point she’d been given a first name and last name like everyone else in town, well, no one had ever known it, not even the women who visited the house each Friday had ever heard her called anything else.

Deadly Myths

By Emmanuel Ordóñez Angulo

The New York Review of Books, January 14, 2021, issue

The novel’s themes—poverty (and all that comes with it: dire working conditions, educational deprivation), repressed sexuality, political corruption, and the opium of religion—all point to its main subject, which is violence. But to list these as elements of a Mexican story is to assert a platitude, and Melchor’s novel is not a catalog of the country’s troubles. Hurricane Season is, first and foremost, a horror story—its horror coming from rather than contrasting with the lyricism of Melchor’s prose.

Architect

By Adrienne Rich

The Paris Review, issue no. 155 (Summer 2000)

You could say he spread himself too thin a plasterer’s

term

you could say he was then

skating thin ice his stake in white colonnades against the

thinness ofice itself a slickened ground

Could say he did not then love

his art enough to love anything more

Could say he wanted the commission so

badly betrayed those who hired him an artist

who in dreams followed

the crowds who followed him

‘Inventing New Ways to Be’

By Mark Ford

The New York Review of Books, November 8, 2018, issue

In the light of Rich’s subsequent career, the terms that Auden used to praise her early work in his introduction to A Change of World came to seem almost comically misguided: her poems, he suggests, are “neatly and modestly dressed, speak quietly but do not mumble, respect their elders but are not cowed by them, and do not tell fibs.” Yet Auden’s somewhat patronizing précis of the virtues of Rich’s debut volume captures some of the cultural assumptions that initially shaped her, as both a poet and a person, and against which she would in time so spectacularly rebel.

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, choose our new summer bundle and purchase a year’s worth of The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for $99 ($50 off the regular price!).

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2U585cR

Comments

Post a Comment