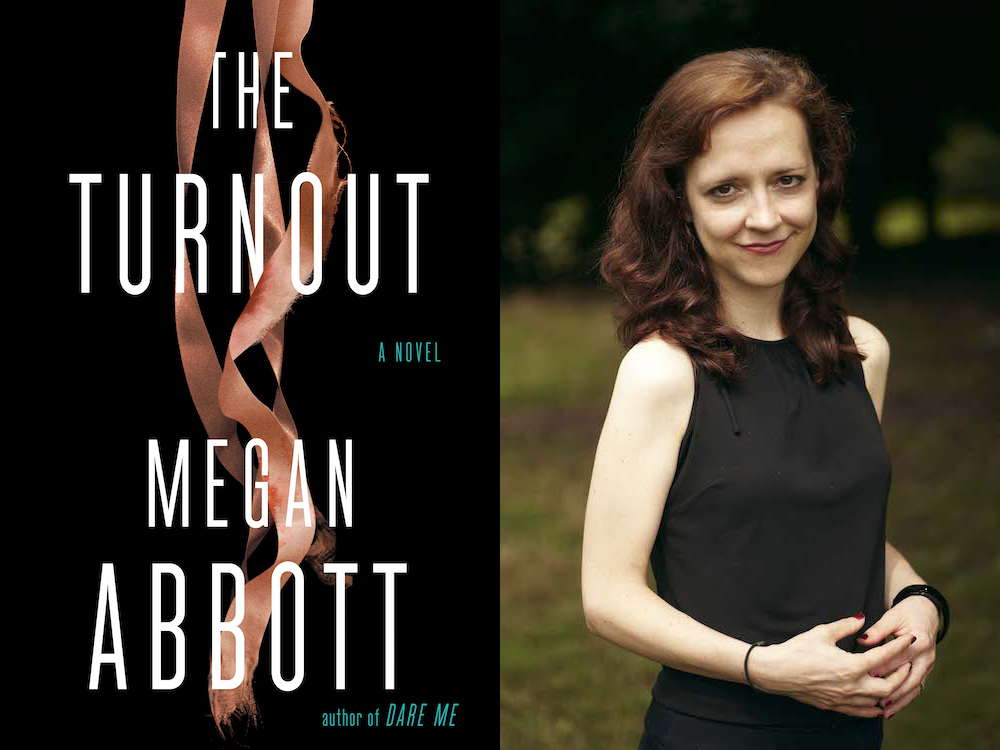

“Ballet was full of dark fairy tales,” Megan Abbott observes in her new novel, The Turnout, noting that “how a dancer prepared her pointe shoes was a ritual as mysterious and private as how she might pleasure herself.” These mysterious and private rituals of young women—these “dark fairy tales”—are at the heart of Abbott’s work. Over the course of ten novels, she’s explored the violence and crime that pervade American girlhood. In Dare Me, competitive cheerleaders become suspects in a murder case. In The Fever, an outbreak of illness is tied to the “enigmatic beauty, erotic and strange” of a small-town high school. While undoubtedly one of our best crime novelists, Abbott has also always struck me as akin to an anthropologist; she not only explores the hidden subcultures of teenage girls but reveals the coded language and shared ethos of their cliques and sects, the way their secrets are not merely secrets but a means of expressing forbidden eroticism, dreams, and rage. In The Turnout, Abbott delves into the rarified world of ballerinas, astutely noting the symbols and signals underlying the romantic image. “There was such a boldness to this girl, a barbarism to her,” she notes. “This pink waif, her tidy bun.”

While she may have the gaze of an anthropologist, Abbott, in fact, began as a Ph.D. student studying film noir at NYU. Her first book, published in 2002, was a prescient work of critical theory, The Street Was Mine: White Masculinity in Hardboiled Fiction and Film Noir. Reading Chandler and Hammett, she’d often wondered, What would happen if the femme fatale told the story? She wrote her first novels, including Bury Me Deep and Queenpin, as sly, meta takes on pulp fiction, with alluring, often menacing women as protagonists. With 2011’s The End of Everything, Abbott began to write about the violence of seemingly all-American girls in seemingly all-American suburbs, gaining not only a wider audience but numerous Edgar Awards and admirers among crime writers. The Wire’s David Simon invited her to be a staff writer on The Deuce, alongside Richard Price and George Pelecanos. More recently, she wrote and coproduced a television adaptation of her novel Dare Me and is now doing the same for The Turnout, while also working on a television series with The Queen’s Gambit’s Scott Frank.

I caught up with Abbott over email during a sultry, tense summer, a summer that felt increasingly Abbott-esque. Boldness and barbarism were everywhere. Heat waves and wildfires seared and scarred. A mysterious illness continued to cause infection and fear, a former America’s sweetheart vowed revenge against her father, angrily confessing a desire to “send him to jail,” while in the music video for the song of the summer, an eighteen-year-old singer posed as a cheerleader easily turns a boyfriend’s bedroom into a sea of flames.

INTERVIEWER

What drew you to write about ballerinas in The Turnout?

ABBOTT

When I was seven or eight, I took ballet classes at this strip mall dance studio where two sisters—twins, actually—were the main teachers. They were so beautiful, in that classically ballet way, and seemed to contain mysteries. I was fascinated by them, their bodies, their rigor, their coolness and elegance. And their wordless exchanges with each other. I wondered what they were like out of the studio. Did the coolness ever slip? Did they have grand romances? Were they close? Growing up in suburban Detroit, I was always yearning for a glamour that felt just beyond, and they seemed to embody everything I longed for—mystery, exoticism, self-containment. And they looked like they held secrets. They became the spark.

INTERVIEWER

Did the coolness ever slip?

ABBOTT

Never. At least not that I saw. But it also seemed so hard to imagine how I—as one of those pigeon-breasted, awkward little girls—would ever become that. It felt unreachable.

INTERVIEWER

I wish I’d had a glamorous teacher! My ballet teacher was very plain and just incredibly unforgiving. I was knock-kneed and shy, and she gave me such a hard time that I dropped out. Meanwhile, my best friend was confident and stuck with it, but later she struggled with anorexia. The rigor and cruelty of ballet are pretty hidden from the public, who just see the tutus and plies. I can see how that contradiction would also interest you.

ABBOTT

Exactly! I was just writing something about that same tension. The idea with ballet, as it is with femininity or womanhood itself, is to hide your work. Keep the fantasy alive.

INTERVIEWER

You showed me a photograph of yourself as a ballerina. How old were you?

ABBOTT

Gosh, maybe ten?

INTERVIEWER

What do you think when you look at it now?

ABBOTT

When I found that picture a few years ago, I had to laugh. That costume, that pose. The eighties were a different time. What I remember, of course, is how excited I was. And how disappointed I was when we got the costumes. They didn’t have the big colorful frills of the cancan dresses in the movies. I’d been expecting something in bright satins with ruffles. I remember our teacher assuring us the light would hit the netting inside and it would look very dramatic! But I was also just old enough to sense a slightly queasy feeling among a few parents.

INTERVIEWER

And when you hit your teenage years, was your rebellion external or internal?

ABBOTT

Mostly internal. My parents were so great and smart and encouraging—big readers, movie lovers, consumers of culture. But my Michigan town and high school were very conservative, and in a very conservative time, the Reagan-Bush years. I just didn’t want to participate in any of that. I was biding my time until I could get to New York City and become Edie Sedgwick or Joan Didion.

INTERVIEWER

You mentioned being inspired by your own ballet teachers, whom you found secretive and glamorous. The teachers in the novel, Dara and Marie, seem to be antiglamour, a bit wounded and angry.

ABBOTT

I guess for me they are glamorous. One of the weirdnesses of writing fiction, for me at least, is how much I love my characters—not despite their messinesses but because of them. And that’s an adult kind of glamour to me. The extremity of their desires, the shame they carry, the intricate blend of rivalry and deep love in their relationship.

INTERVIEWER

And that rivalry and love is complicated by the fact that they’re teaching young girls—they’re mirroring their mother, who taught them when they were young ballerinas. It allows you to explore these cycles of girlhood and adulthood in a very specific way.

ABBOTT

I’ve always thought that was one of the most compelling things about teaching—how you can see versions of yourself. See yourself in the students, as they see a possible future self in you. It’s almost like a haunting. It can be dangerous—as in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie—but I suppose it can save someone’s life, too. It’s a tricky mix of mentorly support and identification. In the case of The Turnout, when it’s familial, too, it’s doubly charged, doubly dangerous, a kind of prison for Dara and Marie—especially somehow for Dara, who hews closer to her mother, who nearly merges with her.

INTERVIEWER

There have been a number of iconic, but very different, films about ballet. In The Red Shoes, for example, ballerinas are the epitome of grace and sophistication, whereas in Black Swan, they’re depraved and masochistic. What do you think of these films?

ABBOTT

Well, I adore The Red Shoes, but I guess, to me, ballet functions more as a stand-in for artistic commitment. Moira Shearer must decide between love and dance and is, in a way, driven mad by it. I love Black Swan, too. In that case, I think ballet is more the director’s vehicle to explore a split self. But I suppose in fiction, ballet is almost always used—consciously or not—as a metaphor for other things. Ballet as body horror, ballet as metaphor for the artist’s plight, ballet as vehicle for backstage drama. It feels inevitable—and I do it, too. It’s so funny, isn’t it, one art form about another art form? A particular challenge. But ballet will likely always be tied up in our culture with ideas about femininity—both potentially confining ones, such as the exacting and specific physical “ideals” of, say, the Balanchine type, and potentially liberating ones, such as strength, discipline, and physical power. And for me, it became a way to explore not just the demands placed on women but the way women are judged, including by one another—as Dara judges her sister Marie for her sexual choices, her erotics. But it also became a way to explore what women demand of themselves and what might happen when they start to free themselves of some of those demands.

I remember my agent reading an early partial draft and saying, But there’s nothing about the beauty of the ballet. And I remember thinking it felt both untrue and beside the point. Because everything, especially beauty, feels different from the inside. When you don’t have to translate it for an audience. When it’s inside you.

INTERVIEWER

The young dancers, like Bailey Bloom, seem to be striving for beauty, but the adults seem warped and broken by age and life—they don’t seem to be fighting for beauty anymore.

ABBOTT

Oh, gosh, for me they are. I guess I define or evaluate beauty differently. For me, the struggle and battle scars are beautiful, far more so than ethereal grace. And I don’t consider them warped or broken but beautiful survivors. They came out of a harrowing childhood, they saved one another, and they’re still growing and changing. For instance, Marie’s desire for freedom is moving and lovely. And Dara’s efforts to keep things the same forever—well, that’s the threshold she has to cross, but she’s not ready yet. How do you give up all the things—order, solidarity, discipline—that kept you alive and whole?

INTERVIEWER

The novel has some very startling twists. Do you plan these with outlines, or are you surprised by where the story goes?

ABBOTT

I planned the big “plotty” ones early on, but there’s one that surprised me, too. Something emerged for me as I wrote, as I figured out the “between” years of Dara, Marie, and their brother Charlie’s early adolescence and the present day. I realized it had to go in the novel or I’d be cheating. Teasing without risking going into the dark center of it. So I just went for it.

INTERVIEWER

Language around the body in The Turnout is very unsentimental and direct, often unsettling. Dara calls her sister “this little pervert” and refers to her own body “down there” as “pink, accordioned … a beetle hole.” She describes a seven-year-old ballerina as “pigeon breasted.” Can you talk about the language? It feels like a subversive choice to avoid being lyrical or adoring about the female body. Was that purposeful or just intuitive?

ABBOTT

Intuitive and shifting. When I write in close third person, I really try to capture the voice, almost as I would in first person. When Dara is upset, angry, frustrated, scared, disgusted—the language flows from that. But I guess, too, I tend to find more “beauty” in messiness, in contortion. It’s a funny thing, but more than one person has noted the recurrence of scars in my novels. I think our battle wounds, and the things we hide or hope to, have a singular beauty.

INTERVIEWER

In my first two books, I found it quite natural to write from the perspective of teenage girls. With my new one, it took me a while to get the tone and style of an older woman’s voice. I guess it’s because there’s such a richness to the voice of someone who is experiencing everything for the first time. How was it for you to write from the perspective of the adult Dara?

ABBOTT

She came very naturally to me. That doesn’t always happen, but I felt I knew her from the start. Her discipline, her need for control—well, perhaps that’s easier for many writers since discipline is required and we love having complete control, even if it’s illusory.

I also wanted to use Dara to animate one of my other inspirations for the book—the way women judge other women’s desires. I’d been very affected by the response to the wildly popular Dirty John podcast and the ensuing TV series, about a woman who becomes unknowingly involved with a serial con man with a string of women in his past who were similarly duped. And I was struck by how listeners frequently laid the harshest judgment on the women for believing him. It was so curious and troubling. An implicit notion that men can’t be expected to be good, so they’re off the hook, but it’s a woman’s duty to see through all this, to never succumb, to conduct herself a certain way, et cetera. In The Turnout, Dara can’t accept Marie’s desires, her willingness to give herself over to desire. And it can make Dara cruel—though really, and I think this is often the case, it’s merely her own anxiety about her own choices, or the leaps she failed to make.

INTERVIEWER

You started out as an academic studying noir, and your first four novels were in the noir genre, albeit from the female point of view. What drew you to noir as a field of study and form of fiction?

ABBOTT

It was entirely the books. I read James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity and The Postman Always Rings Twice and Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep and Farewell, My Lovely in grad school, and I was completely hooked. I’d always loved the film adaptations, but the books rocked me. They were so much more ambiguous, ambivalent, strange, humming with the writers’ own idiosyncrasies. And so full of anxiety—especially about the other, frequently embodied in the so-called femme fatale. They were also just such glamorous books to me, everyone acting on their longings, all the primal emotions, and that moody atmosphere of sex and dread. I was hooked and never really left. I’m still writing my way into that world with every book, even if the trappings change, because those original books just felt like they came from my own weird insides.

INTERVIEWER

The femme fatale, in noir film particularly, is endlessly fascinating to me. She’s allowed to be dangerous and alluring, and yet, she’s almost always punished.

ABBOTT

Often she’s punished, but that’s really predominantly in old-school noir. Though I’m not sure the punishment matters because the hold she retains over those stories and the popular imagination is far greater. And as Mary Ann Doane famously said, the femme fatale isn’t really a person anyway. She’s a projection of male anxiety.

INTERVIEWER

I teach a seminar at Columbia called “Anti-Heroines.” We look at the work of authors like Jean Rhys, Marguerite Duras, Nella Larsen. Aspects of their work—the unlikable woman, for instance—were unsettling or new to my students, but in recent years, there’s definitely been a shift. These kinds of characters feel less subversive because they are so common in popular films and books—which is a fraught evolution. I worry that the bad mother or the troubled teen have become clichés. Have you noticed this shift, in both popular and literary culture?

ABBOTT

I’ve noticed the former, which I love. So many of my favorite books in the past year or so—foremost Raven Leilani’s Luster—have been thrilling to read. The narrator of Luster is such a rich, complicated figure, and the other prominent female figure, who typically would be written as a good wife/mother, is full of her own passions and wildness. I’m not sure I’ve quite seen the latter. Or do you mean the one has turned into the other in the way that everything gets watered down? Last year’s evasive, cruel mother has become this year’s flattened-out, cartoonish “bad mother”?

INTERVIEWER

Yes, that’s a perfect way of analyzing it. We move from one cartoon to another. Are there any recent films or TV shows you’ve seen where the “bad” woman has the complexity of, say, a Don Draper or Travis Bickle?

ABBOTT

It depends how we’re defining bad. Let’s just say women who, by our strict cultural standards, misbehave. There’s been a rich trove of them, from Promising Young Woman to Search Party, from The Queen’s Gambit to Hacks. Elisabeth Moss in almost anything. It’s been an exhilarating moment. Any year when we get to see female-centered and female-crafted works of art as great as Nomadland or I May Destroy You is a good year indeed.

INTERVIEWER

You certainly deserve credit for really taking risks early on in your career and paving the way for other authors to explore the violence in the all-American girl.

ABBOTT

I don’t know if I deserve any. I’m far from alone—in fact, I count you as one of the most eloquent voices in that regard. But if I’m honest, I didn’t even know they were risks. I was just writing girls as I knew them and as I was one. The strength of the taboos about girls and women were far greater than I’d guessed. That need to believe girls and women never have aggressive or violent feelings, never lose control of themselves or are driven by desire.

INTERVIEWER

How was it to move into writing for television, first as a writer with David Simon on The Deuce and then in creating your own show, Dare Me?

ABBOTT

TV writing is so intensely collaborative, and that turned out to be exhilarating. I can’t imagine a more creatively satisfying experience than Dare Me. To have the chance to create this whole shimmering world with others, with the directors, the cinematographer, production designer, costume designer, a room of writers, the brilliant cast and crew all bringing their own ideas to it—it was incredible. But then, after wrap, to get to return to the subterranean world of novel writing is also a relief.

INTERVIEWER

Did you encounter any resistance to your vision of the teenage girls in Dare Me?

ABBOTT

Some, yes. Mostly before we sold it. In the development and selling stages, we would hear things like, Can’t Addy have a romantic interest? If you’ve seen the show or read the book, you know that Addy has two romantic interests—one past and one current—that consume her. But because those interests are women, it was as though they didn’t count. But I think that says less about the feedback and more about that moment in TV, a few years ago now, when shows with teens were supposed to go a certain way—hetero romantic triangles, proms, et cetera. In just a few years, that’s all changed for the better.

INTERVIEWER

I love the interloper character. It’s definitely a noir staple. In The Turnout, the interloper is a contractor, which is a really brilliant way to get at the menace and greed that’s so prevalent in our real estate–obsessed culture. He’s such a villain! It feels like a fun character to write.

ABBOTT

Yes, I loved writing him. Because, like many interlopers, he’s right about many things. He sees things that Dara, Charlie, and Marie can’t see. And he’s mostly right in his taunting guesses about what’s really going on between Dara, Charlie, and Marie, even as his aims are mercenary. I also love these kinds of stories because the question always becomes, Is he the real danger, or are they?

INTERVIEWER

In The Fever, you drew on the true story of “mass psychogenic illness” or “the twitching epidemic” among girls in upstate New York. Can you talk about the role of research in your work? Did you do any investigating or reading for The Turnout?

ABBOTT

Tons. But I always do. It’s really a consuming and exciting process for me. In this case, it was mostly about ballet—memoirs, biographies, nonfiction books, documentaries—and the history of The Nutcracker, but I’ll research anything that makes the story feel more real, its spaces more lived in. I read an enormous amount about renovations gone awry, for instance. The contractor-client relationship can be so fraught. It’s a surprisingly intimate experience, letting someone into your home, giving them reign over it. Or, for the contractor, being in someone’s homes, dealing with their demands and insecurities, getting a bird’s-eye view of everything behind closed doors.

INTERVIEWER

Derek’s intrusion is really chilling. He’s repulsive to Marie, but utterly appealing to her sister. He reminded me a lot of Trump in this way, the perverse charisma, the impossible promises, the shady secrets he is able to conceal. Was Trump on your mind?

ABBOTT

I never thought of it, but how could he not have been? He was on all our minds. Like the pressure of water, you can’t fight it. It gets in.

INTERVIEWER

You will be adapting The Turnout for television. In terms of what we have been talking about, this seems like a really exciting way to break some more boundaries by delving into this world where women can be both graceful and vicious.

ABBOTT

Fingers crossed. Like any dancer, or athlete, or writer, I’m full of superstitions.

Rebecca Godfrey is the author of The Torn Skirt and Under the Bridge.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/379mGHe

Comments

Post a Comment