In 1995, the poet Henri Cole traveled to Italy as the recipient of the Rome Prize in Literature. While there, he spent time with the American painter and photographer Chuck Close, who died last week, aged eighty-one. Recently, Cole came across a notebook in which he had recorded his impressions.

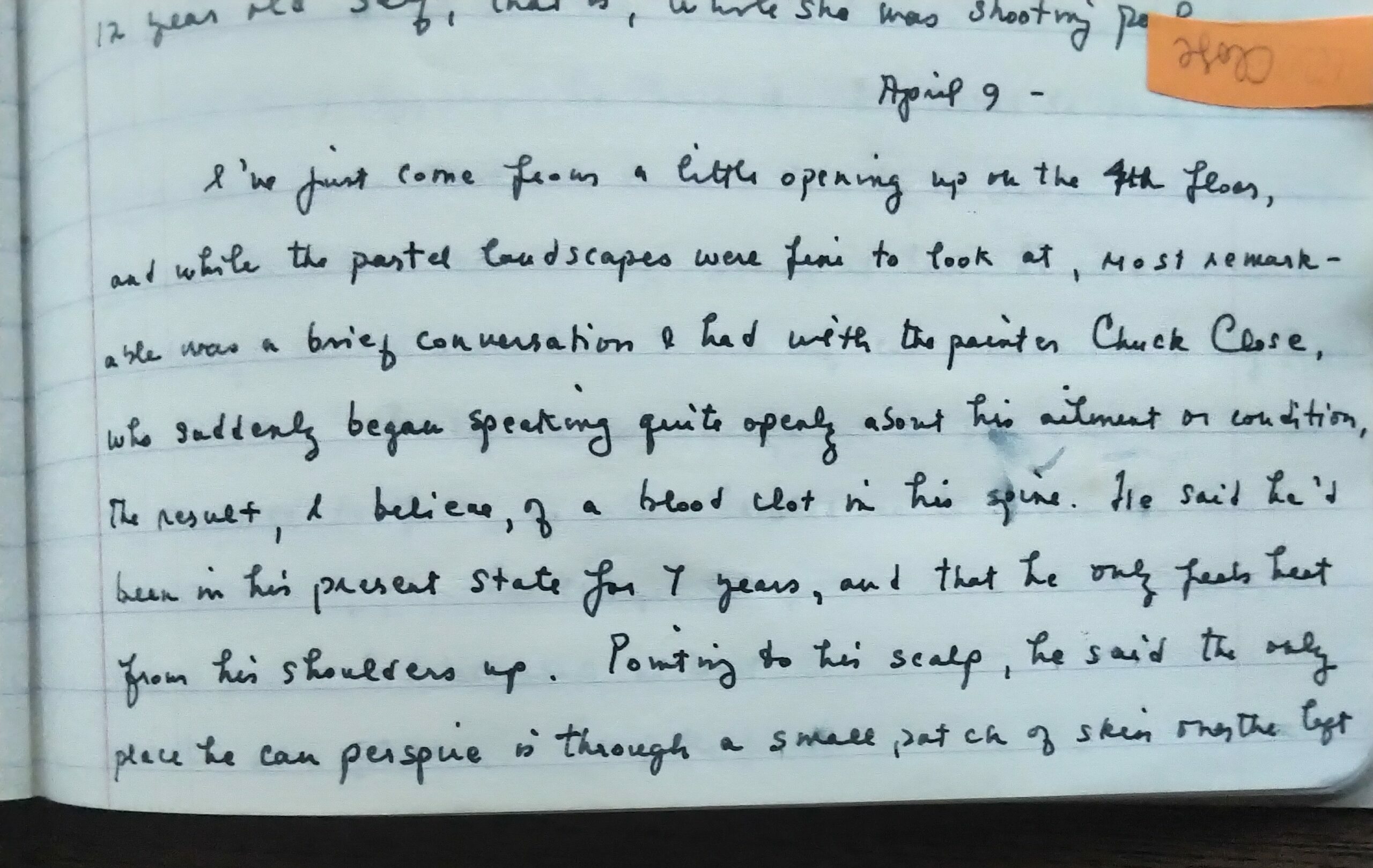

I’ve just come from a little opening up on the fourth floor, and while the pastel landscapes were fine to look at, most remarkable was a brief conversation I had with the painter Chuck Close, who suddenly began speaking quite openly about his ailment or condition, the result, I believe, of a blood clot in his spine. He said he’s been in his present state for seven years, and that he only feels heat from his shoulders up. Pointing to his scalp, he said the only place he can perspire is through a small patch of skin on the left side of his head. When he is touched anywhere below his shoulders, what he feels is an icy cold. He is happiest in the sun in his bathing suit.

When he paints, he straps his brushes to his wrists. It is easier for him to paint than to draw, because he can paint with his arm out before him; to draw requires more mobility than he has. He talked with such candor that a small group of us was drawn to him. When a child toddled by and stared at him, he said children were always curious about him because they couldn’t understand why he was in a stroller. He said it was strange not to feel what he knows he’s supposed to feel, and then he asked me to touch his hand. His definition of pain has changed completely, he told me, since almost everything he feels is pain. If there is a blessing in his condition, it is that it is not degenerative. It is hard to object to his smoking and drinking, seeing the pleasure he takes in them.

He said he was not a believer in the “adversity makes the artist stronger” theory, though it does seem that he is living proof of this. He said that when he started off painting, all his works were De Koonings. Later, once he’d developed his own style, he was able to return to the De Kooning palette, which he loves. He said that he was always subtly altering the variables in his paintings so that they’d evolve in some modest way. He said he did not prefer one or the other sort of artist; that is, one who was constantly remaking himself as opposed to one who was not. When I said that I did not really think of myself narrowly as a “gay poet,” he said he understood completely, because though he is a photorealist painter, he does not admire the work of other photorealists and believes this connection to be superficial.

***

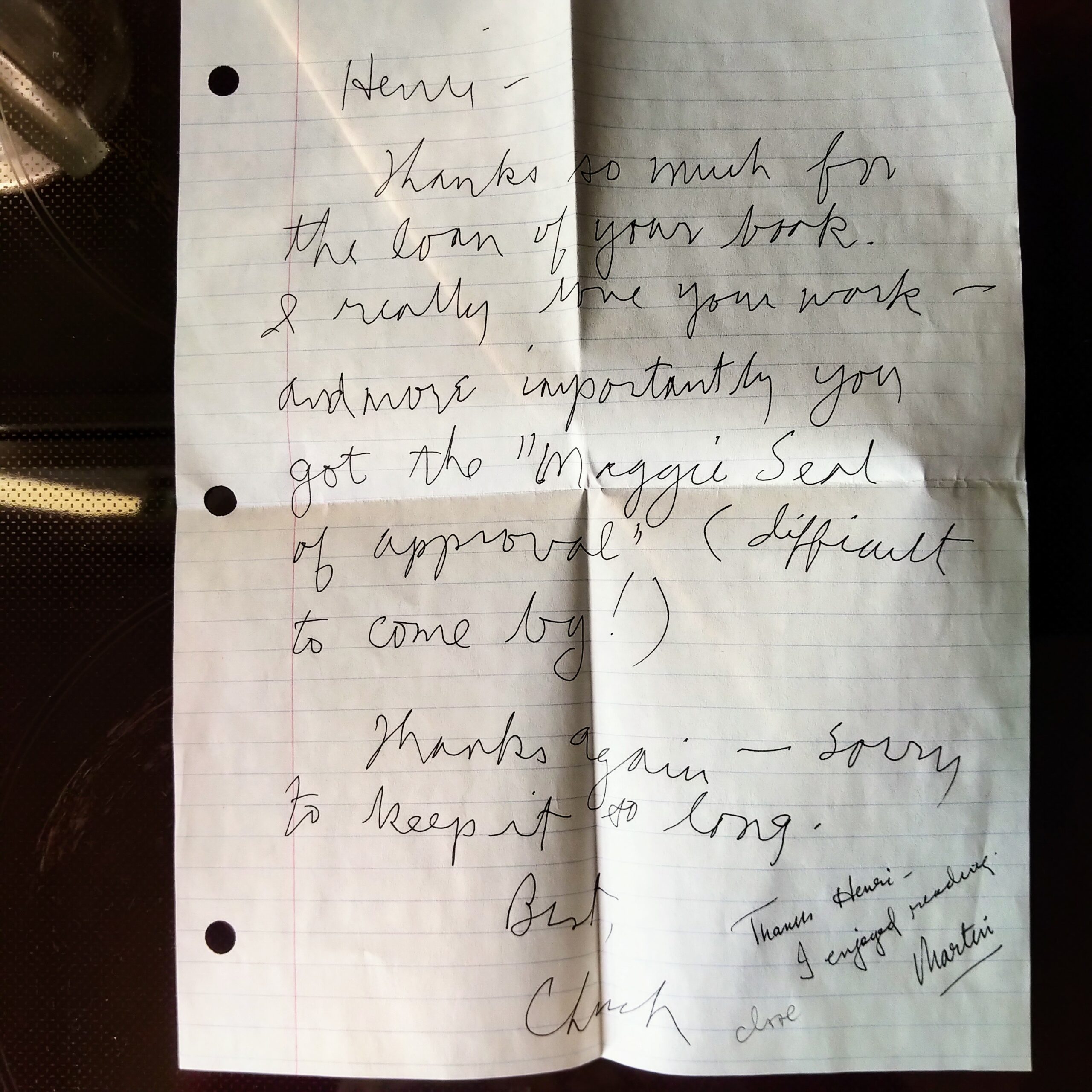

He invited me to visit him in his studio overlooking Trastevere and when I arrived there was a violent rainstorm blowing water through the oversize windows. A big puddle grew at our feet. He sat in an armchair and spoke of the grid painting of his daughter, Maggie, in process on his easel. He said that painting the small grid squares was like playing golf and that each hole was about a par four or five, meaning that he usually needed to return that often with his brush to each grid to get it right. Of course, I thought of James Merrill calling poetry word golf—“in three lucky strokes of word golf LEAD/ Once again turns (LOAD, GOAD) to GOLD.” Chuck also used the analogy of archeology, of digging deeper and deeper until the thing he sought emerged from the paint. When I suggested that his method of composition was rather like a poet’s—which is to say cumulative, word by word, line by line—he said he always felt he had more in common with writers than painters. And, indeed, his canvas was aslant on the easel, like a sheet of paper on a desk.

Henri Cole was born in Fukuoka, Japan. He has published ten collections of poetry, most recently Blizzard, and a memoir, Orphic Paris. A selected sonnets is forthcoming.

Works by Chuck Close appeared in Issue no. 75 (Spring 1979) and Issue no. 207 (Winter 2013) of the Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3jnziBf

Comments

Post a Comment