Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re celebrating another year of the best deal in town: our summer subscription offer with The New York Review of Books. For only $99, you’ll receive yearlong subscriptions and complete archive access to both magazines—a 34% savings!

To give you a taste, we’re unlocking pieces from the archives of both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books. Read on for Robert Lowell’s Art of Poetry interview, paired with his letters to Elizabeth Bishop concerning the founding of The New York Review of Books; Ingeborg Bachmann’s short story “Everything,” paired with Merve Emre’s essay on Bachmann’s novel Malina and other fiction; and a portfolio of art by Kara Walker, paired with an essay by Zadie Smith on Walker’s work through the years.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, poems, and works of criticism, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books and read both magazines’ entire archives?

Robert Lowell, The Art of Poetry No. 3

The Paris Review, issue no. 25 (Winter–Spring 1961)

The ideal modern form seems to be the novel and certain short stories. Maybe Tolstoy would be the perfect example—his work is imagistic, it deals with all experience, and there seems to be no conflict of the form and content. So one thing is to get into poetry that kind of human richness in rather simple descriptive language. Then there’s another side of poetry: compression, something highly rhythmical and perhaps wrenched into a small space. I’ve always been fascinated by both these things.

Founding the New York Review: Two Letters from Robert Lowell to Elizabeth Bishop

By Robert Lowell

The New York Review of Books, November 6, 2003, issue

Here we are in the hectic whirl of putting out the new book review. I’m very much a bystander and admirer. But Lizzie is furiously engaged and in a way making inspired use of her abilities—for God knows we need a review that at least believes in standards and can intuit excellence.

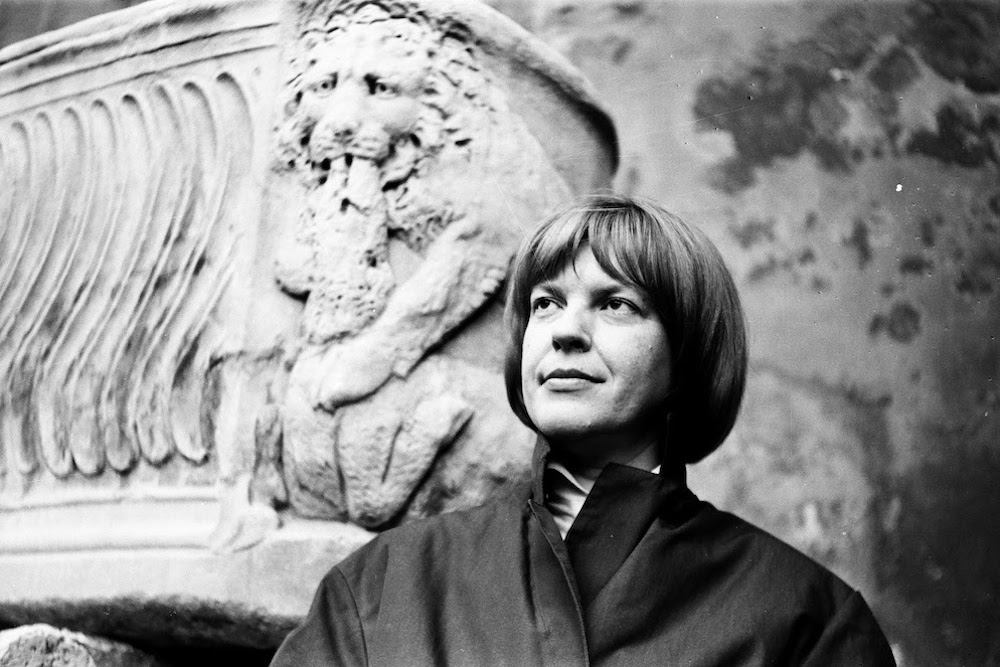

Everything

By Ingeborg Bachmann, translated by Eithne Wilkins & Ernst Kaiser

The Paris Review, issue no. 28 (Summer–Fall 1962)

And suddenly I realized: it’s all a question of language, and not merely of this particular language of ours, which was created with all the other languages at the Tower of Babel in order to bring confusion into the world. For under them all there’s another language smouldering away, a language that extends into gestures and glances, into the evolving of thoughts and the ebb and flow of emotions, and it’s here that all our griefs begin. It was all a question whether I could save the child from our language until he had founded a new one and could so begin a new era.

The Meticulous One

By Merve Emre

The New York Review of Books, October 22, 2020, issue

Today her novels remain unnerving for how desperately they struggle to give visible form to the invisible and private injustices perpetrated by men, to name them with the same certain horror that attends to accusations of fascism. Though no one pulls a trigger or slashes a knife or even lays hands on the women in her novels, Bachmann calls them “victims” and describes the betrayals that preceded their deaths as “crimes.” “It was murder,” proclaims the last sentence of Malina—a murder for which no one will be held accountable because no one appears to have done anything wrong.

Kara Walker’s interview at the Camden Arts Centre, London (8m44s). Interview by Anna McNay and filmed by Martin Kennedy. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

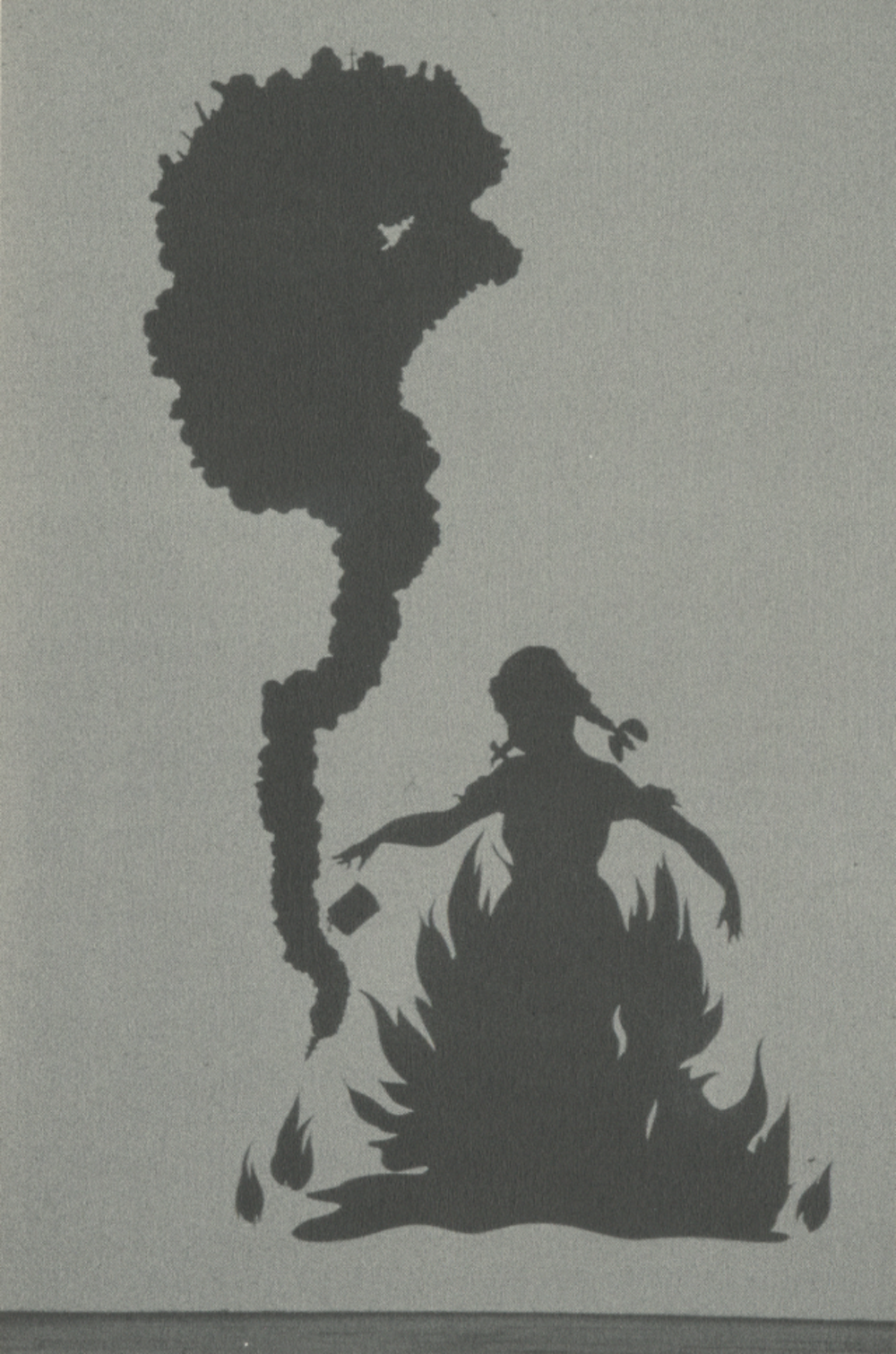

Silhouettes

By Kara Walker

The Paris Review, issue no. 153 (Winter 1999)

What Do We Want History to Do to Us?

By Zadie Smith

The New York Review of Books, February 27, 2020, issue

Walker’s particular mode of engaging with our attention spans—her visual and conceptual provocations—have often caused furor, first from the generation above her, now not infrequently from the generation below. For when it comes to the ruins of history, Walker neither simply represents nor reclaims. Instead she eroticizes, aestheticizes, fetishizes, and dramatizes.

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, choose our new summer bundle and purchase a year’s worth of The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for $99 ($50 off the regular price!).

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3jKMA9R

Comments

Post a Comment