In Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be.

In the final months of 1922, people all across the United Kingdom were gripped by a cause célèbre. In the early hours of October 4, Percy Thompson, a shipping clerk, and his wife, Edith, a twenty-eight-year-old bookkeeper and buyer for a millinery business, were making their way home after a trip to the theater in the West End. About a hundred yards from their house in Ilford, a lower-middle-class suburb in North-East London, a man suddenly appeared, stabbed Percy multiple times in the face, neck, and body, and then raced off into the night. Percy died almost instantly. Reporting on the event the following day, the Times declared that the details were still “a mystery,” and that the police were waiting for Edith to recover enough to be able to “give a coherent account of the incidents preceding her husband’s death.” Then, only twenty-four hours later, the case took an unexpected twist when the police announced that they’d charged two persons: Edith and a twenty-year-old ship’s steward named Frederick Bywaters, who had for a short time been the Thompsons’ lodger.

Edith and Bywaters had been conducting an illicit affair for the previous eighteen months. Their correspondence, written while Bywaters was away at sea, had been found by the police and was being used as evidence for the prosecution. By the time the trial began—two months later, on December 6, at the Old Bailey—much of the content of these letters was already all over the press. Every day the court’s public gallery was packed. The enterprising unemployed began queuing outside as early as 4 A.M., selling their spots to those with money in their pockets who arrived later in the day. For those unable to afford these escalating prices—in his book Criminal Justice: The True Story of Edith Thompson, René Weis reports that by the final day of the trial a seat in the gallery was going for more than the average weekly wage—the Times reproduced verbatim transcripts from each day’s proceedings. On Monday, December 11, the jury announced their verdict: both defendants were found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. As he was removed from the dock, Bywaters was still protesting that Edith was innocent, as he had done throughout the trial—a refrain that she herself loudly took up as the reality of her fate sunk in. Sobbing and screaming, she was half dragged, half carried back to the cells to await her execution.

That it was Bywaters who’d attacked Percy was never really in doubt. The question at the heart of the trial, and the reason it had captured the public’s attention, regarded Edith’s involvement in the murder. The case against her rested on the seventy-odd letters she had exchanged with Bywaters. They weren’t just proof of the affair; they also revealed that Edith had purchased abortifacients to get rid of an unwanted pregnancy—two factors that, given the social mores of the era, couldn’t have been any more damning. The judge presiding over the trial exhorted that “right-minded persons” should be “filled with disgust” by the shameless content of Edith’s missives. Further, the letters were used as evidence of incitement to murder. In them Edith talks about wanting to rid herself of Percy so that she and Bywaters could be together. “Yesterday I met a woman who had lost 3 husbands in eleven yars [sic] and not thro [sic] the war, 2 were drowned and one committed suicide and some people I know cant [sic] lose one. How unfair everything is,” she writes to him on November 18, 1921. In subsequent dispatches she also claims to have fed Percy ground-up glass, and to have tried to poison him. Yet no evidence of any such attempts on his life was found during the postmortem, thus supporting Bywaters’s argument that they were “mere melodrama,” conjured up by Edith’s overactive imagination, all part of her notion of the affair as a grand romance. The jury, however, didn’t believe him. Instead, Edith was painted as a deadly femme fatale, earning her the nickname “the Madame Bovary of North-East London.”

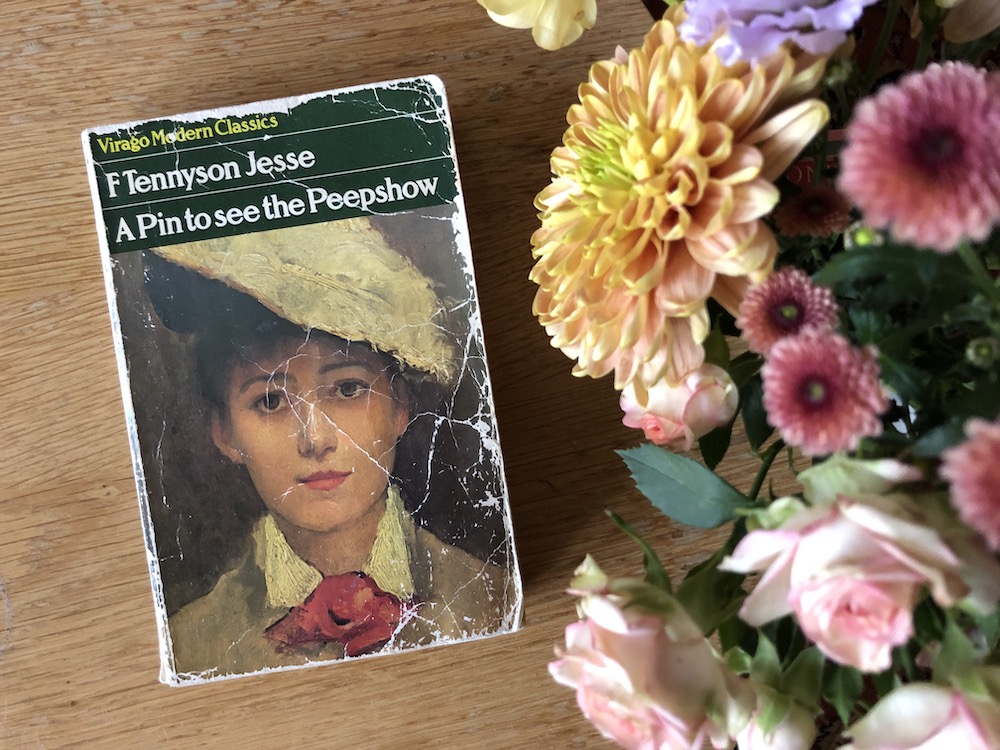

In 1934, the popular novelist, playwright, and criminologist Fryn Tennyson Jesse published A Pin to See the Peepshow, a novel inspired by the case. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the TLS’s reviewer, Orlo Williams, draws a direct line between Flaubert’s passionate, unfulfilled provincial doctor’s wife and Jesse’s Julia Almond, her fictionalized Edith Thompson. “It is a theme that can never grow old, and to take it up is an enterprising calling for every gift at a novelist’s command,” Williams writes, praising the “bravery and distinction” with which Jesse carries it off. Significantly, though, Jesse’s heroine is categorically not a murderer; she’s just a frivolous suburban wife whose romantic fantasies ultimately cost her her life.

*

Jesse—whose great-uncle was the famous Victorian poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson—was thirty-four years old at the time of the trial. Like others across the country, she was riveted—so much so, in fact, that she saved all the material she could find relating to the case, including myriad newspaper reports. As her biographer Joanna Colenbrander details in A Portrait of Fryn, the harshness of the verdict had “shocked” her greatly. Already the author of two novels, a volume of short stories, a collection of poems, and a large body of journalism (including her work as an intrepid war reporter in France for the Daily Mail during World War I), Jesse hadn’t yet turned her formidable talents to criminology, but this was a field in which she soon became a recognized expert.

In 1924 she published Murder and its Motives, in which she classifies six key motivations for this heinous crime—murder for gain, murder for revenge, murder for elimination, murder from jealousy, murder from lust for killing, and murder from conviction—and illustrates each with a notable real-life case study. The book was a great success. “It has been observed, with some truth, that everyone loves a good murder,” reads the opening line, something that the Daily Telegraph’s review picks up:

The intensity of public interest in the leading cases of the past two or three years is eloquent proof that the love of a ‘good murder’ was never more keen than it is today. Moreover, the increasing attention paid by the newspapers to what is known professionally as ‘distinguished crime’ renders more easy the intimate study by the man on the street of the reasons underlying the taking of life.

The reviewer then goes on to praise Jesse’s “acute analysis of criminal psychology,” which, they argue, is impressive enough to override any “surprise” the reader might experience on discovering that a woman—shock horror!—had seen fit to concern herself with such unsavory subject matter. The editor James Hodge so admired the book that he asked Jesse to join his roster of introducers for the Notable British Trials series, which had been published by William Hodge and Company since 1905 and was a great favorite with readers keen for every salacious detail of the most notorious criminal cases of the day. Colenbrander notes that Hodge’s original letter was addressed “Dear Mr Jesse,” which provides further proof of just how daring Jesse’s interest in crime was. Not that Hodge’s later discovery of Jesse’s sex put him off. “By the clarity and pungent humour of her style,” explains Colenbrander, “Fryn established herself as one of James Hodge’s favourite contributors.” She went on to write introductions to six volumes in the series.

As such, by the time she wrote A Pin to See the Peepshow, Jesse had already proven herself a dab hand at dissecting criminal proceedings, which makes it all the more intriguing that the trial takes up a mere quarter of the novel. Instead, her focus is firmly on her tragic heroine—Julia was the book’s original title—both in terms of her particular individual psychology and the impact that broader conventions regarding her gender and class had on her fate. Colenbrander quotes a letter Jesse wrote to her Paris agent explaining that the novel is the story of “the life of an over-emotional, under-educated, suburban London girl, who had no more idea of murder than the unfortunate Mrs Thompson had.”

Her origins may be humble—her father is “only a clerk”—but even as a schoolgirl, Julia firmly believes that’s she’s meant for bigger and better things. When we first meet her, she’s an impressionable teenager lost in “her own secret life,” an imaginary world “woven purely of reminiscences of novels and her own desires.” At school, she’s bored by Shakespeare, but at home she’s enchanted by the wild romantic story of Lorna Doone, and she spends hours daydreaming about being whisked away by a handsome Prince Charming. Later, as a young working woman, she gets a job at an elegant West End couturier called L’Etrangère, and shortly thereafter begins a romance with an attractive young man named Alfie. Tragically, as with so many of his generation, he’s killed in World War I.

Time passes, and although Julia’s career is going from strength to strength as she works her way up the ranks at L’Etrangère, she’s still dealing with disappointments on the domestic front. Following the death of her father, she and her mother have to share their home with Julia’s aunt, uncle, and cousin in order to make ends meet. Thus, when an older man—a recently widowed family friend named Herbert—starts to court her, Julia is swept up by his attentions and impetuously agrees to marry him. In his dashing wartime uniform, he appeals to the “dreaming Julia,” the woman “who had been loved by Lewis Waller, and an Italian prince, and Lord Kitchener, and Dennis Eadie, and by a wonderful warrior yet unmet.” Her illusions are shattered, however, when Herbert returns from the war and transforms back into the same ordinary gentleman’s outfitters’ employee he was before he went away, “only older, balder, fatter, duller.” During his absence, Julia relished her independence, but now she’s expected to be a devoted wife, always eager to please. Her discovery—that “a man didn’t necessarily give a woman the sensations she craved, although he attained them for himself”—is yet another blow to her rich fantasy life.

Though tame by today’s standards, Julia’s subsequent reactions against the tyranny of convention—she refuses to give up her job, insisting on earning her own money; seeks out a backstreet abortionist rather than have Herbert’s child; and takes a younger lover (Leo Carr, the Frederick Bywaters character)—are, by those of the period, her class, and her sex, scandalous. Like Emma Bovary before her, she has no particular feminist agenda; she’s not at all interested in the women’s suffrage movement. Her rebellion is couched purely in terms of her romantic expectations. Unfortunately, her refusal to conform has tragic consequences. Although she plays no part in the scuffle that occurs late one night between her lover and her husband—in the course of which Herbert meets his death—and she has no prior warning of Leo’s decision to confront his rival, she finds herself charged with murder, vilified as a predatory older woman with dangerously loose morals, in exactly the same way that Edith was in real life.

*

“I am not, and never have been, a feminist or any other sort of an ‘ist’,” writes Jesse in her first volume of belles lettres, The Sword of Deborah: First-Hand Impressions of the British Women’s Army in France, “never having been able to divide humanity into two different classes labelled ‘men’ and ‘women.’” All the same, and as Colenbrander illustrates, Jesse was absolutely someone who spent her life “speaking up for women,” and firmly believed in their rights. Indeed, the jacket flap of The Sword of Deborah carries this message from the author:

It appears to me that people should still be told about the women workers of the war and what they did, even now when we are all struggling back into our chiffons—perhaps more now than ever. For we should not forget, and how should we remember if we have never known.

Jesse demonstrated a radical degree of independence throughout her life, both financially and otherwise. She married late, when she was thirty, and it was anything but a traditional union, not least because as per her husband’s wishes, they kept the marriage a secret for the first three years, which gave rise to a rather unusual situation in which he treated his wife as his mistress, and his mistress—with whom he’d already fathered a child—as his wife. But Jesse’s views on both marriage and motherhood were advanced for the era. “The very idea that a woman should remain married, or submit to bearing children, to a man she did not love, was shocking and repugnant to her,” Colenbrander writes. Jesse believed that “divorce should be at least as easy for a wife as for a husband; [and that] abortion should be at her discretion and made safe.” These, of course, were exactly the issues at stake in the abasement of Edith Thompson. She was condemned for adultery and for terminating a pregnancy she did not want. There was no actual evidence to prove that she’d had a hand in her husband’s murder, and both she and Bywaters continually proclaimed her innocence, yet still the jury found her guilty. But where the gatekeepers at the time saw a woman who was a menace to society and an aberration to her sex, Jesse saw a misunderstood victim.

She was not the only one to believe that a miscarriage of justice had occurred—various journalists expressed concern at the time of the trial and the execution—but she was the first person to explore the perfect storm of events that culminated in Edith’s untimely death, and to empathetically portray this woman—or a woman very like her—with deep understanding and compassion. Julia isn’t always very nice. She’s vain, narcissistic, and conceited, but she’s also trapped in a marriage she no longer wants to be in. The upper-class women she encounters at L’Etrangère live by different rules: they can take lovers, discreetly, with an ease that’s completely unavailable to the lower-middle-class Julia. And as for her vivid fantasy life, well, Jesse expertly illustrates that this is in large part a product of a society that imposes unfair limitations on young women. Many writers have turned their attentions to the abuses in this criminal case—including Edgar Lustgarten in Verdict in Dispute and Lewis Broad in The Innocence of Edith Thompson: A Study in Old Bailey Justice—but despite its relatively early publication, A Pin to See the Peepshow’s take on the story puts it on par with more recent works, namely Weis’s aforementioned Criminal Justice and Laura Thompson’s Rex v Edith Thompson: A Tale of Two Murders, a feminist reading of the case that argues that Edith was the victim of a “gendered” trial swayed by a climate of prejudice against female sexuality.

One of the most accomplished elements of the novel is the way in which Jesse conjures up the desperation and claustrophobia that her misjudged heroine feels as the net tightens around her. Julia’s breakdown in the dock when the sentence is passed makes for brutal reading. As the judge’s voice—“in the same calm, unemotional tone he had used throughout”—rings out across the courtroom, she experiences the moment as if she’s descending into a nightmare: “Julia heard her own voice screaming: ‘But I didn’t know. I didn’t know!’ and then the people closed about her and she was taken away.” But as powerful as this is, it’s nothing compared to the horror of the hours running up to her execution. Her mind rendered “mercifully numb” and her body moving “slowly and draggingly” due to the quantity of sedatives she’s already been given, Julia’s taken from her usual cell to another, at the end of a long corridor:

Then she saw at the far end of the cell another door, a small, arched door, painted green, and in a flash it came upon her where she was. It was through that door that she would have to pass tomorrow morning, twelve hours from now … only twelve hours from now.

Then she screamed and fought, and went mad, and tried to climb up the green wall, scrabbling at it with her nails, but she felt arms all about her, holding her down. She went on screaming; somebody had shut the cell door, and it seemed full of people. Then there came the prick in her arm, and fight and scream as she would, she felt a dullness coming over her legs and arms, and her head fell forward.

They laid her on the bed, and arranged the blankets over her. She mustn’t go to sleep—she mustn’t. She was losing precious time. She must talk to them, explain how it had all happened. Surely she could show them that they mustn’t do this dreadful thing?

The “writing acquires an extraordinary power as the narrative nears its conclusion,” writes the novelist Sarah Waters. “Jesse wants us to be unable to look away from it—as if, as members of the society in whose name she is being destroyed, we have a duty to bear witness to her destruction, a duty to watch.” In Waters’s own novel, The Paying Guests, which is loosely inspired by the Thompson and Bywaters case, she gives the story a radical revisionist twist. Not only does she substitute a lesbian romance for a heterosexual one, but The Paying Guests goes one step further in that it also rewrites the traditional rules of female sexual transgression that called for the transgressor’s punishment. Waters’s lovers, Lilian and Frances, narrowly escape the hangman’s noose, and as the novel draws to a close, we leave them together and free. Poor Julia receives no such reprieve. Just like the real-life Edith, she’s hanged at Holloway Prison. A Pin to See the Peepshow is not just a gripping story with an unforgettable heroine at its heart; it’s also an important record of the appalling misogyny and prejudice fostered by the early-twentieth-century British judiciary establishment.

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, the Financial Times, The New York Times Book Review, and Literary Hub, among other publications. Read earlier installments of Re-Covered.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3sZMm37

Comments

Post a Comment