Louise Bourgeois, The Destruction of the Father, 1974, latex, plaster, wood, fabric, and red

light. Collection Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland. © The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

The exhibition rooms on the second floor of the Jewish Museum are densely shadowed and cavernous, the scant light artificial and angular. In one, the mouth of a veined brown marble fireplace hangs open, eating air. It’s an apt setting for the exhibition “Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s Daughter,” which traces the artist’s fraught relationship to psychoanalysis, including her reactions to her own thirty-three years of treatment. Journal entries, dream fragments recorded on scraps of paper, fabric works, the iconic Passage Dangereux (1997), Destruction of the Father (1974), and Ventouse (Cupping Jar) (1990) constitute only a portion of the show. A cluster of Bourgeois’s writings speak to her relationship to sadism, fear, self-destruction. But I wasn’t surprised to find myself orbiting the texts swollen with guilt, anger: “A germ of rage cohabits like the germ of TB, it lives in you.” I could have spent an entire heliophobic day trying to make out Bourgeois’s handwritten notes, which slip between pictorial and linguistic representations just as fluidly as they shift from English to French. I’ll be back before September 12, when the show closes. —Jay Graham

Many narratives of millennial “love,” if that’s the right word for it, depict a quest for a functional partner of similar class status with a good skincare regimen and perhaps a willingness to engage in light s/m just to make sure things aren’t completely bland, which they are. Blandness is not a vice that afflicts the characters in Matthew Gasda’s play Quartet, which is showing at Ty’s Loft, in Greenpoint, the next two Saturdays. (I saw it this past month at another loft, in TriBeCa.) Leave questions of likability and probity at the door: these people betray each other and themselves, and their betrayals are collaborative affairs fueled by alcohol, other intoxicants, and secrets past and present. The play is funny and caustic, it’s all in the lines, and the actors go for it like it was the seventies, though I don’t know if I would trust Mike Nichols with it. —Christian Lorentzen

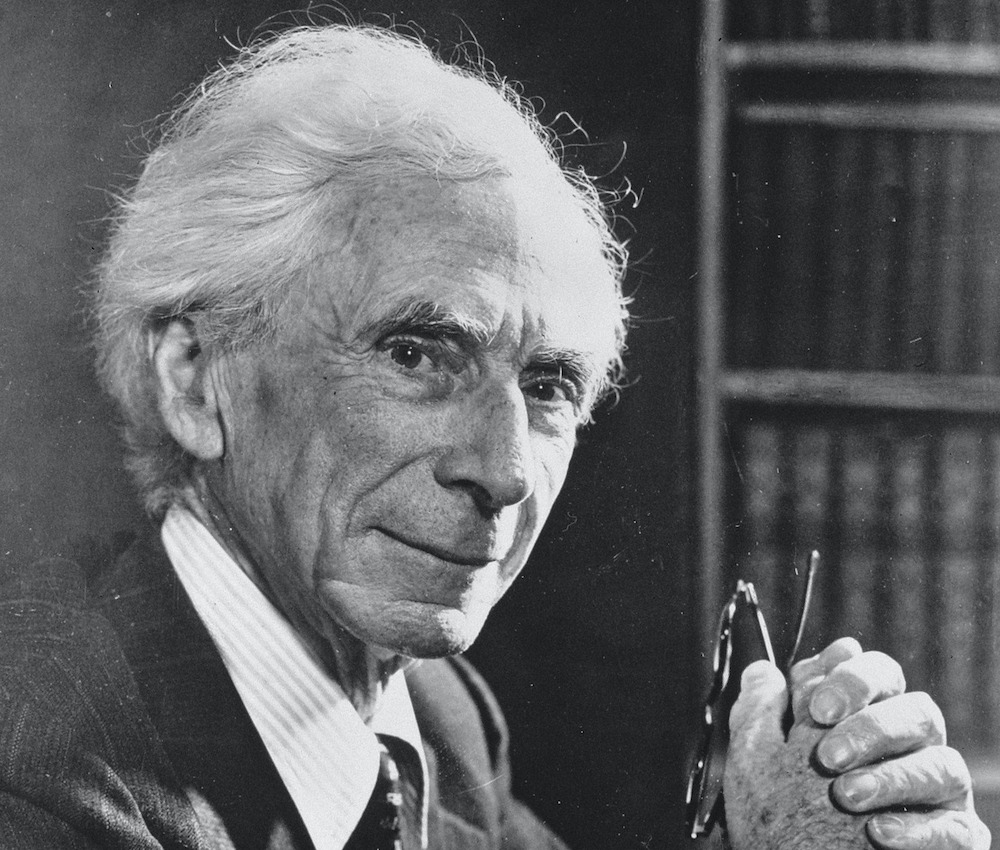

Self-help wasn’t yet a cultural fixture when Bertrand Russell published The Conquest of Happiness, in 1930. And in a way, it feels strange to classify the book in that genre, given that it’s written by a philosopher of mathematical logic who is best known for his Principia Mathematica, a book of formal proofs that Daniel Dennett has called “one of the most unreadable great books ever written.” But despite his technical genius, Russell believed that philosophy should, first and foremost, teach one how to live, and The Conquest of Happiness contains pragmatic advice that remains eminently useful. Burnout, he notes, stems not from overwork but from anxiety and indecision. Boredom is usually caused by excessive vanity and can be cured by taking interest in something outside of oneself. Since first reading the book earlier this year, I have thought often of his aphorisms on envy (“The sin against the Spirit consists of knowing a thing to be good and hating it because it is good”) and his observations on how an expansive perspective can alleviate trivial annoyances (the anger over a broken bootlace can be remedied, he argues, by reflecting “that in the history of the cosmos the event in question has no very great importance”). Intelligence does not always entail wisdom. To find both in a single mind is a rare gift. —Meghan O’Gieblyn

What are you doing this weekend? If you don’t have any plans, may I suggest you spend literally all of your waking hours binge-listening to two new jazz box sets, both of historical interest but for very different reasons? The first is Lee Morgan’s The Complete Live at the Lighthouse, which comprises twelve live sets of explosive but accessible jazz from 1970 by one of the stalwarts of the classic Blue Note sound. I’d always avoided Morgan’s albums, thinking them too light for my tastes; I now stand corrected. This music is relentless and edgy, a surprising mix of Morgan’s trademark sixties funk and something darker and more desperate. The band, which had been working together for a year or two, is at its peak, and this is a great opportunity to see what the multi-instrumentalist Bennie Maupin can really do if given free rein. The other box is Anthony Braxton’s Quartet (Standards) 2020, a record of a tour just before the pandemic in which the veteran avant-gardist took a group of edgy UK musicians on a jaunt around Europe, playing nothing but jazz standards but doing them his way, meaning with equal reverence and irreverence. This group tackles the Great American Songbook, John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins, Miles Davis, and even a bit of Paul Simon. This is an accessible pathway into Braxton’s expansive universe, and a parade of his sometimes stuttering, sometimes careening solos. There’s more than twenty hours of music between the two boxes, so your weekend should be covered. —Craig Morgan Teicher

When she was young, Natalia Ginzburg would repeat phrases to herself that she found particularly pleasing. “I dress in brown” was one such phrase, taken from Annie Vivanti’s The Devourers. Another was one of her own invention: “Isabella is leaving.” I found myself similarly drawn to a phrase in Yu Miri’s Tokyo Ueno Station (translated from the Japanese by Morgan Giles): “When I lived with my family, we took no photos together.” —Robin Jones

Read Christian Lorentzen’s interview with Mike Edison and Meghan O’Gieblyn’s “Does Technology Have a Soul?”

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3Dp4WpV

Comments

Post a Comment