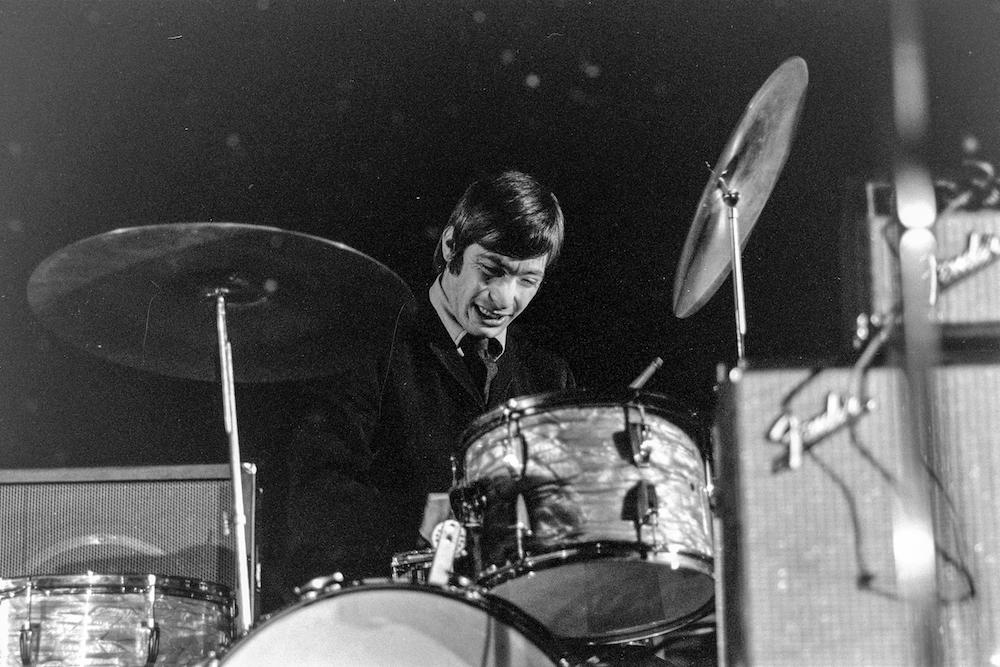

Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones during a concert at the Royal Lawn Tennis Stadium in Stockholm, 1965. Photo: Owe Wallin. © Tobias Rostlund / Alamy Stock Photo.

The drummer Charlie Watts died on Tuesday, aged eighty. Watts took up the drums as a child after cutting the neck off his banjo and converting it to a snare. Born in London during World War II, the son of a truck driver and a homemaker, he was a jazz aficionado from the age of twelve, and went to art school in his teens. In 1963, the Rolling Stones hired him away from Alex Korner’s Blues Incorporated, and Watts—cultivating a stoic demeanor and known for his refined fashion sense—remained a member of the band until his death. Mike Edison’s 2019 biography Sympathy for the Drummer is a work of music criticism in the spirit of Lester Bangs. Watts did not speak to Edison for the book, but after its initial publication he called the author and left him a message: “Hi, you don’t know me, my name is Charlie Watts, I want to thank you for writing this lovely book… and for having Charlie Parker on your voicemail…” Later they spoke, and Watts invited him to come see him when the Stones got back on tour. Unfortunately, the pandemic intervened and kept the band off the road. I spoke to Edison about Watts and the Stones on Thursday morning.

INTERVIEWER

What made you write a book about Charlie Watts?

MIKE EDISON

It took me forty-five years to write this book! In the interim I’ve written thirty-something other books. But when I started playing the drums when I was a kid, I knew this was a cypher I had to crack. Charlie Watts is so special, and so deceptively simple, I knew it wasn’t the kind of thing you can ever truly learn. It’s the kind of thing you have to live with—you have to breathe with it, you have to vibrate close to the frequency that he was working on. You know, you can go on YouTube and look up “How to play like Charlie Watts” and you will find almost nothing, because you can’t teach it. But search for “How to play like Rush” and you’ll find twelve thousand kids playing “Tom Sawyer” flawlessly in their bedrooms, because you can learn how to do that.

So, with Charlie Watts, listen to the hi-hats opening up in the weirdest places, the off-kilter rolls, an accent that in other hands would have been a mistake, things other people would never allow to make it onto a record. All those snare-drum riffs and tattoos he does at the beginning of songs where he’s speeding up to catch up with Keith—sometimes he even gets ahead of himself before Keith comes in. Some very professional drummers have told me they would get fired if they played like that, and they say that in awe. The sloppy-but-tight thing is what makes it work. So much of the personality of the Stones comes from the drummer—you know it’s the Stones from the snare drum, even before Mick Jagger starts his caterwauling.

INTERVIEWER

The Stones famously passed through different phases—R&B, psychedelia, blues rock, disco, reggae. How are those phases reflected in Charlie’s drumming?

MIKE EDISON

The stork didn’t deliver Charlie Watts to the Rolling Stones’ doorstep as a fully developed drummer. On the early records they’re basically a talented cover band. On “Satisfaction,” he opens up and starts stomping—that’s the beginning of punk rock, at least in any mainstream sense. It’s relentless and very aggressive, especially live. And that guy is not the same guy who’s playing on “Street Fighting Man” and “Gimme Shelter” a few years later, where there’s more nuance. “Rip This Joint,” which opens Exile on Main Street, is the fastest song in their whole catalog. It’s like a splatter painting. He’s gone from impressionism to extreme impressionism. The band has gone from playing songs to playing music. Charlie goes from just playing the drums to playing the band.

In the early seventies, the Stones are at their absolute pinnacle. Ladies and Gentlemen, the Rolling Stones, the document of their 1971–1972 tour, is the apex. It’s vicious. I sit and listen to it and reconsider everything I do. From there, it did roll off, there’s no question. As Keith said, Mick had “a ticket to Jetsville,” and was busy falling in love with himself for the twenty-fifth time. He wanted to hang out in Hollywood. Keith had a ticket to Dopesville, the opposite direction. They weren’t showing up for work at the same time, and Jimmy Miller, their great producer—it’s hard to hang around these guys and not pick up their bad habits. Goats Head Soup suffers for it, It’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll suffers. There’s a murkiness to the recordings. Goats Head Soup always sounds to me like there’s dirt on the needle.

INTERVIEWER

Didn’t they record that in the Caribbean?

MIKE EDISON

In Jamaica, because it was the only place Keith was allowed to go, drug addict and felon that he was. It was exciting because Dynamic Sound Studios, where they recorded most of The Harder They Come, was the O.G. reggae studio. Going to Kingston, Jamaica, was not like going to Switzerland or Paris.

INTERVIEWER

How does Charlie figure in the moves they made toward reggae and disco?

MIKE EDISON

Mick always wants to make the record he heard in the club the night before. He loves chasing trends, and that’s where they always step in it, like trying to copy the Beatles on Satanic Majesties Request, trying to be au courant or some goddamn thing. But what people may not know is that Charlie loved dance music, too. He would go with Mick to discotheques in Munich. He loved the Sound of Philadelphia, Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, all of that. He loved Motown. And you can hear how good he is at playing it, not just on “Miss You” but on all the disco songs on Emotional Rescue, too. The drums sound so sharp. This is all part of Charlie’s evolution. They’d always been making dance music, it just wasn’t called “disco” yet, things like “Fingerprint File” or “Hot Stuff.” The big mystery is how they managed to put over “Miss You” at a time when rock ’n’ roll fans were screaming, “Disco sucks!” For them to make a dance record was on brand, the Stones were all about great Black music, but it just happened to be at the same time when the Kinks and Pink Floyd had copped the disco beat, because that was what some suit told them they had to do to stay in business. That big hi-hat swoop of Charlie’s is what seals it for the Stones disco records. He knew how to do it right.

As a reggae player, Charlie doesn’t really do the one-drop thing. It’s reggae-like—if you listen to “Cherry Oh Baby” on Black and Blue, he is really teasing all around it but the groove is still very deep. Black and Blue, that’s a very underrated record. There are some great songs like “Hand of Fate” but a lot of it is just jams, like “Hey Negrita” or “Crazy Mama.” It’s not overproduced. It’s just guys playing together.

INTERVIEWER

They were auditioning guitar players. Did you ever hear that Neil Young said he felt disappointed that he wasn’t asked to try out?

MIKE EDISON

I had not heard that! I always thought Johnny Thunders would have been good for that role, but maybe two junkies in the same band wouldn’t have been a such good idea. Ronnie Wood seems like the right guy, right? You know, by Some Girls, a gauntlet had been thrown down by the Sex Pistols and others. And if you listen to that record, especially “Respectable” and “When the Whip Comes Down,” they’re playing some very convincing punk rock, but if you unfurl it, it’s all just country riffs. That tour was fantastic because it was the last time they felt like they had something to prove—they really did not like being called old men. Remember, they were in their thirties! But no one could yet imagine a sixty-year-old Bruce Springsteen coming down the road. The 1978 Stones tour was brutal, they just said, Fuck you. After that things became more corporate.

INTERVIEWER

Is there any redeeming the Stones’ output after Tattoo You in 1981? Millennial fans seem to have rehabilitated all of Bob Dylan’s late work, whereas there was a time when everything he did after Blood on the Tracks and Desire was considered dreck.

MIKE EDISON

No, no, no, no, no. Bob Dylan lost his way in the eighties, but the solo acoustic records of the early nineties got him back to his roots, which is a music-industry cliché but true in his case, and much of what he’s done since has been great.

INTERVIEWER

Can the same be said of any late Stones record?

MIKE EDISON

The last great Stones song is “Had It with You,” on Dirty Work, generally considered their worst record. “Had It with You” is just nasty, primitive and raw, no bass, grinding drums, Mick pouring out the anger, the great trash cymbal Charlie Watts plays—it’s really mean and it’s sleazy. It’s punk rock.

INTERVIEWER

Steel Wheels, Voodoo Lounge, Bridges to Babylon? I’ll put my cards on the table, I think Bridges to Babylon, from 1997, is a really good record.

MIKE EDISON

You can always find a moment, and largely because of Charlie. If you notice, over the years, he keeps getting louder in the mix. From Tattoo You on, the snare drum starts to sound like a machine gun. It really becomes their signature sound, and they knew it.

INTERVIEWER

What about Charlie’s solo records where he returned to jazz?

MIKE EDISON

Charlie was the only one of the Stones who made perfectly lovely solo records that were beyond criticism. He was just pursuing his passion, and it was beautiful. Nobody’s going to confuse the Charlie Watts Quintet with Charlie Parker’s band or the Max Roach Quintet, but I saw him on tour and he had the biggest smile on his face, like the Cheshire cat. It took over the stage. But you know, even with a pretty good Keith record, you still wish you were listening to the Stones. When Mick started making his own records, Keith said, “Fuck off, disco boy. You’re really gonna go play with the Schmuck and Balls Band when you could play with the Stones? If you wanna make an album of Irish ballads with Liberace, do it, but if you wanna make a lousy rock record, do it with the Stones.”

What’s shocking, the last surprising thing, was the Stones’ blues record from 2016, Blue & Lonesome. I expected something kind of droll, maybe I would play it a few times—but then I found myself playing it over and over again. Charlie’s shuffles are impenetrable, and so hard to play. That’s the genius of Charlie, and it goes back to when Brian Jones and Keith Richards sat him down in the early sixties and said, Listen to Jimmy Reed, you gotta learn this. They made him internalize it. It is repetitive, it is a tempo that almost drags but somehow never does. There’s that extra breath between things, and it is so hard to play. This is the reason why most blues bands at the local bar suck. The Doors are like the worst thing imaginable. They’re a blues band that can’t play the blues. Despite all their bona fides and all the other things they might do well, their John Lee Hooker sucks, their Bo Diddley is craven, they ought to be arrested for their Howlin’ Wolf. They didn’t do their homework the way Charlie did. Somehow white guys got the idea that it was easy to play the blues, and it is not.

Christian Lorentzen lives in Brooklyn.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3sTvr2f

Comments

Post a Comment