Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re thinking about psychoanalysis and the interpretation of dreams. Read on for Adam Phillips’s Art of Nonfiction interview, an excerpt from Sigrid Nunez’s novel The Friend, Joanna Scott’s short story “A Borderline Case,” and Mark Scott’s poem “Freudian Tenderness,” as well as selections from a 1984 portfolio of Louise Bourgeois drawings.

Interview

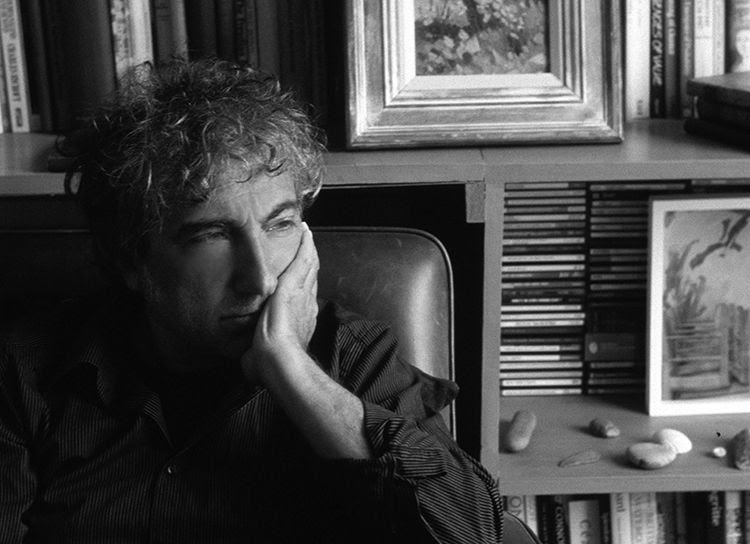

Adam Phillips, The Art of Nonfiction No. 7

Issue no. 208 (Spring 2014)

Psychoanalytic sessions are not like novels, they’re not like epic poems, they’re not like lyric poems, they’re not like plays—though they’re rather like bits of dialogue from plays. But they do seem to me to be like essays, nineteenth-century essays. There is the same opportunity to digress, to change the subject, to be incoherent, to come to conclusions that are then overcome and surpassed, and so on.

Fiction

The Blind

By Sigrid Nunez

Issue no. 222 (Fall 2017)

The doctors who examined the women—about a hundred and fifty in all—found that their eyes were normal. Further tests showed that their brains were normal as well. If the women were telling the truth—and there were some who doubted this, who thought they might be malingering—the only explanation was psychosomatic blindness. In other words, these women’s minds, forced to take in so much horror and unable to take more, had managed to turn out the lights.

This was the last thing you and I talked about while you were still alive.

Fiction

A Borderline Case

By Joanna Scott

Issue no. 123 (Summer 1992)

This is the story of K and B, analyst and patient; specifically, this is the story of their first session together, before K had cured his patient, “dispersed” B, as he’d say, helping him to become “more B than ever before.”

Poetry

Freudian Tendencies

By Mark Scott

Issue no. 155 (Summer 2000)

Freud liked to collapse distinctions:

masochism is the continuation

of sadism (“nothing but”), in which

one’s own person takes the place

of the sexual object; so looking

is analogous to touching; is based

on touching, is base in so far forth;

but neither the lingering at the touching

nor the lingering at the looking

satisfies the libido, the lust …

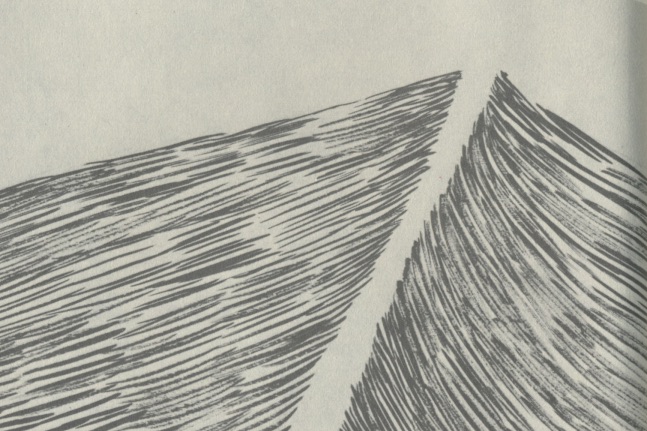

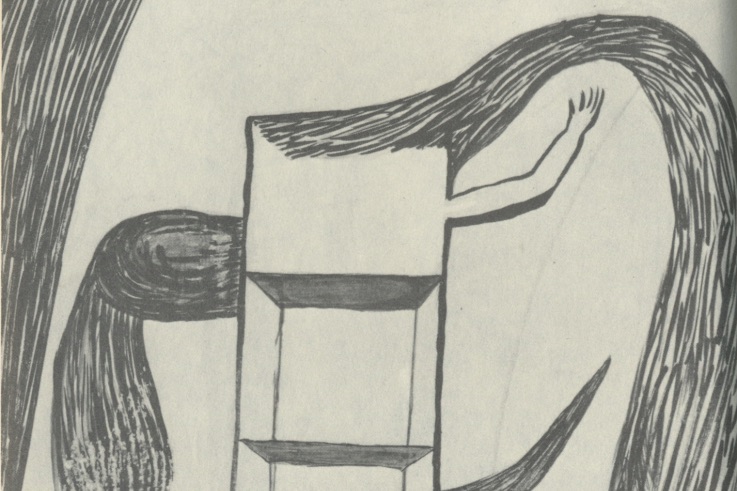

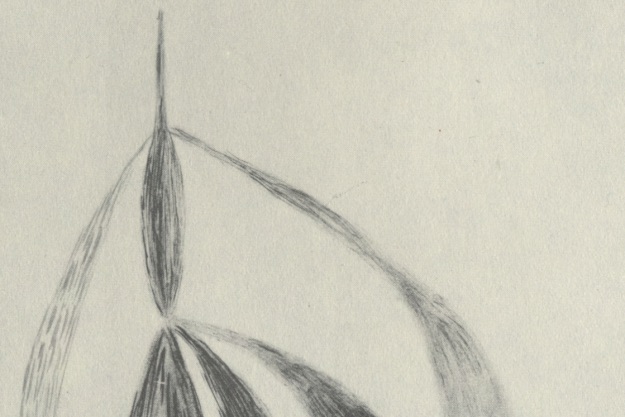

Art

Drawings from the 1950s

By Louise Bourgeois

Issue no. 92 (Summer 1984)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3F2eKr1

Comments

Post a Comment