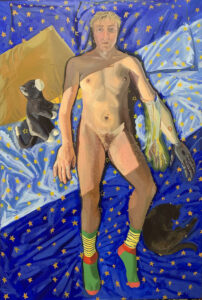

Linus Borgo, Bed of Stars: Self-Portrait with Elsina and Zip, 2021, oil on canvas, 46 x 68″ (detail).

Linus Borgo makes consistently uncanny and gorgeous work, some of which will be featured at Steve Turner Gallery in Los Angeles this January. My favorite of their self-portraits—deadlocked with Fuzzy FTM Transsexual Amputee Plays with Magic Wand and Poppers (Self Portrait)—is Bed of Stars: Self Portrait with Elsina and Zip, in which Linus lies in a pool of deep blue, star-stamped sheets, an oblique banner of sunlight across his torso and thighs, his body filling the frame, toes nearly poking through the border. It’s a work that questions what it is to reproduce an image, a pet, a body part. Of course, this is the terrain of figurative art. But duplicates also appear within the piece: Linus’s left bionic forearm and its phantom mirror not only each other, but his right forearm; the cat dozing by his ankle complements the stuffed one cradling his elbow; the bedspread underneath him simulates the sky above. The effect is overwhelming, and intensified by meticulousness: blades of hair golden in the sun, creases in the pillowcase, a naval piercing, cursive lettering on a nameplate necklace. In this representation of the self, there is an abundance of selves existing side by side simultaneously. What more could you ask for in a self-portrait? —Jay Graham

Tice Cin’s debut novel, Keeping the House, would be interesting for its subject matter alone—it follows the heroin trade in London’s Turkish communities in the late nineties and early 2000s. But what really sets it apart is its snaking, shifting form, filled with constant interruptions by Turkish Cypriot words, and their English definitions, embedded in the middle of the page. The result is a book filled with as much stop/start energy as the raves its characters attend. —Rhian Sasseen

The albums of legendary indie rock band Superchunk—and the solo projects of their front man and Merge Records co-owner Mac McCaughan—have been a refuge for me since the midnineties, when I swaddled my tortured teenage self in their seminal album, Foolish. For decades McCaughan released his solo material under the moniker Portastatic, but with his 2015 album Non-Believers, he came out under his own name with a clean, eighties-inflected vibe. His follow-up, The Sound of Yourself, is out today. It’s a mature statement from an indie veteran who knows exactly what kind of music he wants to make: mellow guitar rock gently buttered with synth, with McCaughan’s trebly voice swimming in and out of the mix like a melancholy dolphin. The spacious title track is a particular favorite. McCaughan also channels his film scoring work with a few lovely, haunting instrumentals. I’m not exactly sure who this record is for—but it could be for me, entering middle age, looking back on all the music that’s moved me, and grateful to pause for a while in a place I know and love. —Craig Morgan Teicher

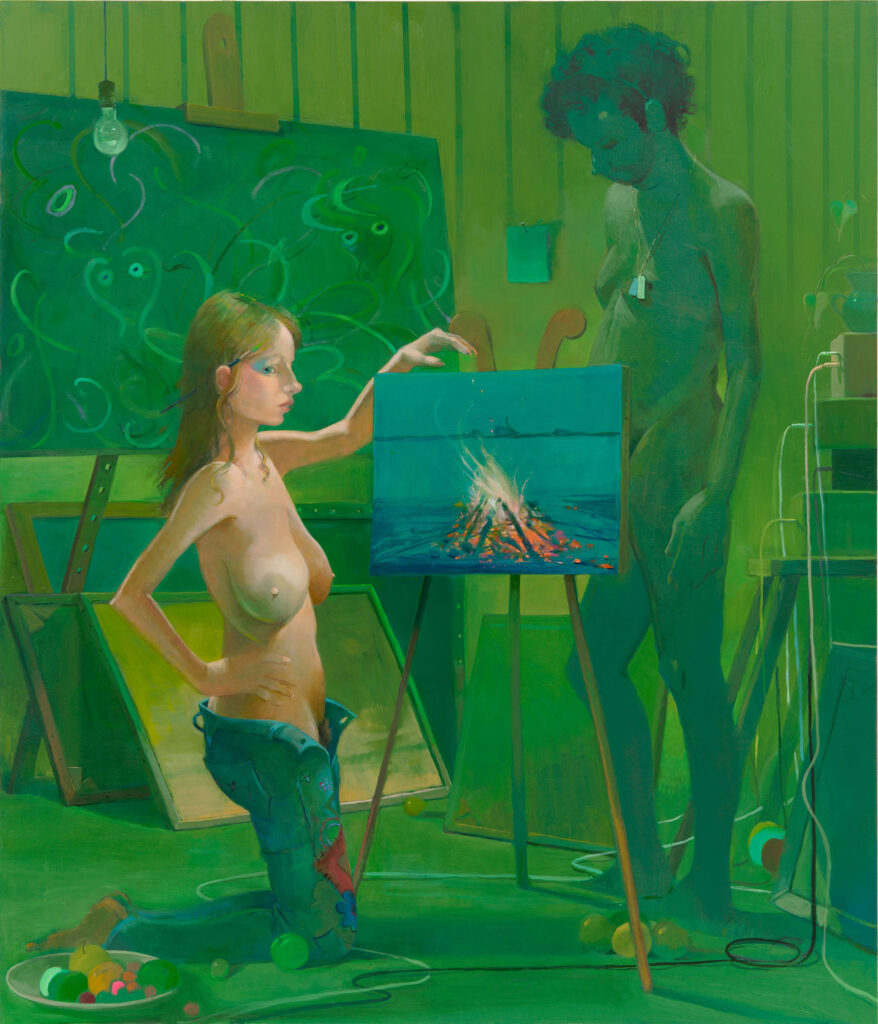

I thought of Jeffrey Skoblow’s In a Trance: On Paleo Art while looking at Lisa Yuskavage’s “Master Class” (in her show New Paintings, up now at David Zwirner). The painting stages a mythic discovery-of-art(ifice)-as-porn scenario: a bare-breasted hippie chick kneels before her male counterpart; they’re separated by a painting of fire, placed over his crotch. Behind them looms a green canvas suggesting the cave-art shapes of horned bison, with a swirly psychedelic twist. Skoblow’s meditation on cave drawings, in which he reconstructs from decades-old, hastily scrawled notebook entries his visits to twelve Lascaux-type sites, looks long and hard at that which is “not a sign of anything but itself, that is, it means, ‘I mean,’ ‘I have meaning,’ and connects all who recognize it.” Skoblow’s prose is quiet, strangely secretive, where Yuskavage’s monochromes are shamelessly pop-y. But both invite us into “a ritual landscape … a place to return to (if only in the mind), to take an interest in the minds and bodies of (relatively distant) others.” Both are lushly recursive and metareferential in harnessing their respective media to ask after the origins of mark-making and figuration, to illustrate and illuminate “the muck and mire of human being, the terrifying crazy ooze of our psychosexual evolutionary mud bath.” Who were these early humans? What did they see? And what did they do, to the walls and each other? —Olivia Kan-Sperling

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3lV0esn

Comments

Post a Comment