First Letter for beyond the Walls

Something happened to me. Something so strange that I still haven’t figured out a way to talk about it clearly. When I finally know what it was, this strange thing, I will also know the way. Then I’ll be clear, I promise. For you, for myself. As I’ve always meant to be. But for now, please try to understand what I’m trying to say.

It is with significant effort that I write you. And that’s not just a literary way of saying that writing means stirring the depths—like Clarice, like Pessoa. In Carson McCullers it hurt physically, in a body made of flesh and veins and muscle. For it is in my body that writing hurts me now. In these two hands you cannot see on the keyboard, with their swollen veins, wounded, bursting, with wires and plastic tubes attached to needles inserted into veins inside which flow liquids they say will save me.

It really hurts, but I will not stop. Not giving up is the best I can offer you and myself right now. Because this—you ought to know—this which could kill me, is the only thing I know that can save me. Maybe one day we will understand.

For now, I am still somewhat caught up in that strange thing that happened to me. It’s so vague, calling it that, the Strange Thing. But what could it have been? A disturbance, a vertigo. A maelstrom—I love this word that spins like a living labyrinth, dragging thoughts and actions into its ever-faster-spinning, concentric, elliptical coils. Something like that happened in my head, and I had no control over the coils’ magnetic endpoints, which swirled out in new spirals so that everything would begin again. Later, everyone was discreet, and I didn’t ask too many questions, either—equally discreet. I should have screamed, and said seemingly meaningless things, and thrown things everywhere, maybe hit people.

I can only remember fragments of what happened to me—fragments so broken that. That—that there is nothing after the that of fragments—broken. But there was the metal gurney, with hooks that clamped around the person’s body, and my two wrists were firmly bound by these metal hooks. My feet were naked in the cold dawn. I screamed for socks, for the love of God, for all that is most sacred, I wanted a pair of socks to cover my feet. Even bound like an animal on the metal gurney, I wanted to protect my feet. Then there was the round spaceship-like machine where they stuck my brain to see everything that was going on inside it. And they saw, but they didn’t tell me anything.

Now I see cold, white buildings beyond the barred windows of this place where I find myself. I don’t know what will come next—it hasn’t been long since the Strange Thing, the disturbance that crashed upon me. I know you don’t get what I’m saying, but understand—I don’t either. The only thing I care about is writing these words (and every word hurts) so that later I can slip them into the pocket of one of my afternoon visitors. They’re so sweet, bringing apples, magazines. I think they’ll be able to carry this letter beyond the walls I see separating these barred windows here from those cold, white buildings.

I fear these others who want to open up my veins. Maybe they’re not so bad, maybe I just don’t understand the way they are yet, the way everything is or has become—myself included—since the great Disturbance. All I can do is write—that is the truth I relay, if I can get this letter beyond the walls. Listen well, I’ll repeat it in your ear, many times: All I can do is write, all I can do is write.

O Estado de S. Paulo, August 21,1994

*

Second Letter for beyond the Walls

On the road to hell I met many angels. Throngs, flocks in flight, phalanxes. Fat, baroque cherubs with their little asses out; shrill seraphim with pale faces and satin wings; stern archangels, swords drawn to confront evil. So on the road to hell, naturally, I met demons too. And the entire hierarchy of the celestial servants armed against them. Weapons of good, weapons of light: no pasarán!

Not as celestial as you’d expect, these angels. The morning ones wear white uniforms, masks, caps, gloves to fight infection. And there are those that carry brooms, pails of disinfectant. They collect their wings and scrub the floor, change the sheets, serve coffee—while others take blood pressure, temperature, auscultate chest and abdomen. Meanwhile, the sneering midafternoon angels wear jeans, black leather, bleached hair, bring candy, newspapers, clean socks, copies of Renato Russo’s cassette celebrating the Stonewall victory, news of the night (where all the angels are gray), messages from other angels who couldn’t make it because of imbroglios, or laziness, or they lovingly feel no need to prove their love.

And when I’m alone, later, I try to watch the purple coloring of twilight beyond the cypresses in the cemetery behind the walls, but the angle doesn’t allow it, so I contemplate the fury of the overpass instead, but it doesn’t matter—ugly or beautiful, everything in life and movement balances. I open windows for the electric angels of the night. They come through antennas: phones, batteries, wires. Sometimes they look like Cláudia Abreu (both of them—my brave sister and the Gilberto Braga actress), but they can have Billie Holiday’s ruined voice, lost on FM, or the deepening creases around José Mayer’s bitter mouth. Men, women, you know—angels have never had a sex. And some work on TV, sing on the radio. In the middle of the night, fed up with ruffling wings, lyres, lace, and cornets, I plummet into the plastic sleep of tubes piercing my chest. But still the angels insist, having come from the Other Side of Everything. I recognize them one by one: against Derek Jarman’s blue background, to the sound of a Freddie Mercury song, choreographed by Nureyev, I identify Paulo Yutaka’s Noh dance steps. Laughing with Galizia Alex Vallauri peeks out from behind The Roasted Chicken Queen, and oh! How I’d love to hug Vicente Pereira and have one more Santo Daime with Strazzer and one more trip to Rio with Nelson Pujol Yamamoto. Wagner Serra pedals his bike beside Cyril Collard, while Wilson Barros rails against Peter Greenaway, with Néstor Perlongher’s support. To the sound of Lory Finocchiaro, Hervé Guibert continues his endless letter to the friend who did not save his life, while Reinaldo Arenas slowly runs a hand through his light hair.

So many, my God, those who have gone. I wake with Cazuza’s suggestive voice repeating in my cold ear, “Whoever has a dream doesn’t dance, my love.”

I wake, and say yes. And everything starts again.

At times they all seem to be coming from the banks of the Narmada River, where the blind singer boy, the ugliest woman in India, and Gita Mehta’s wealthy monk strode. At times, I think that they are all dogs carrying badges in their teeth, their front paws burned by cigarette butts so that they dance better, like in that story that Lygia Fagundes Telles sent me. And at the same time, I think how whenever I see or read Lygia, I am stunned by beauty.

So I repeat, that which I thought was the road to hell is strewn with angels. That which seemed dismally cursed held a thread of light. On this narrow thread, stretched like a tightrope, we all balance. Umbrella held high, one foot in front of the other, fearless dancers at the end of this millennium hover above the abyss.

Down below, a web of wings cushions our fall.

O Estado de S. Paulo, September 4, 1994

*

Last Letter for beyond the Walls

Porto Alegre. Happy Port—I suppose you found the two previous letters obscure, enigmatic, like those in almanacs of old. I’ve always enjoyed mystery, but I enjoy truth more. And since I think it’s superior, I am writing more clearly for you now. I feel neither guilt, nor shame, nor fear.

I returned from Europe in June feeling sick. Fevers, sweats, weight loss, spots on my skin. I found a doctor and, in his absence, took the Test: That One. After an agonizing week, the result: HIV positive. The doctor had gone to Yokohama, Japan. Test in hand, I spent three days normally, telling my family and friends. On the third night, with friends over, feeling safe, I went crazy. I don’t know the details. Maybe I don’t remember out of self-protection. I was taken to the ER at Emílio Ribas Hospital with a suspected brain tumor. The next day I woke up from a drugged dream in a bed in the infectious diseases ward, my sister entering the room. Then there were twenty-seven days inhabited by frights and angels—doctors, nurses, friends, family, not to mention our own—and a current of love and energy so strong that love and energy welled up inside of me, until they became a singular thing. That from without and that from within united in pure faith.

Life handed me misery, and I didn’t know that the body (“my brother ass,” as Saint Francis of Assisi would say) could be so frail and feel such pain. Some mornings I cried, looking through the window at the white walls of the cemetery across the road. But at night, from the right angle, when the neon lights lit up, Doutor Arnaldo Avenue looked like Boulevard Voltaire in Paris, where there’s a Sufi angel who watches over me lives. In that moment everything felt right. Free of resentment or disgust, just the immense agony of that thing, Life, inside and outside the windows, beautiful and fleeting like butterflies who survive only one day after leaving the cocoon. For there is a cocoon breaking open slowly, a dry, abandoned husk. After that, the flight of Icarus chasing Apollo. And the fall?

I welcome every day. I tell you because I don’t know how to be anything if not personal, shameless, and being so I must tell you: I have changed but remain the same. I know you understand.

I also know that others think only immoral people get this science fiction virus. For them, remember Cazuza: “We seek mercy, Lord, mercy for the cowardly and narrow-minded.” But to you, I humbly disclose: what matters is Dear Lady Life, covered in silver and gold and blood and the moss of time and sometimes whipped cream and confetti from some carnival—revealing her horrific and dazzling face little by little. We must accept it. And kiss her on the lips. Strangely, I’ve never been so well. Armed with Saint George’s weapons. The walls are still white, but now they are the walls of a Spanish colonial house, which makes me think of García Lorca; the gate can be opened anytime to come or go; there is a palm tree, and pink roses in the garden. This place is called Menino Deus, as sung by Caetano, and I always knew the port was here. You never know how safe it is, but—in the words of Ana C., who stops me at the window’s edge—since you can’t anchor a ship in space, it is anchored in this port. Porto Alegre. Happy Port. Happy or not: Ave Lya Luft, Ave Iberê Camargo, Quintana and Luciano Alabarse, che!

I watch Dercy Gonçalvez, on Hebe; I attend Gabriel Vilella’s The Deceased at the Teatro São Pedro; Maria Padilha tells me previously undisclosed stories about Vicente Pereira; I split sushi with the Antônia Bivar actress Yolanda Cardoso; I pray for Cuba; I listen to Bola de Neve; I burst out laughing with Déa Martins; I use all four hands to draw with Laurinha; I read Zuenir Ventura to understand Rio; I wear the red star of the Worker’s Party on my chest (“Who knows?”); I open the I Ching at random: Shêng, the Ascension; I never miss my telenovela Éramos Seis and I am grateful, grateful, grateful.

Life screams. And the struggle continues.

O Estado de S. Paulo, September 18, 1994

—Translated from the Portuguese by Ed Moreno

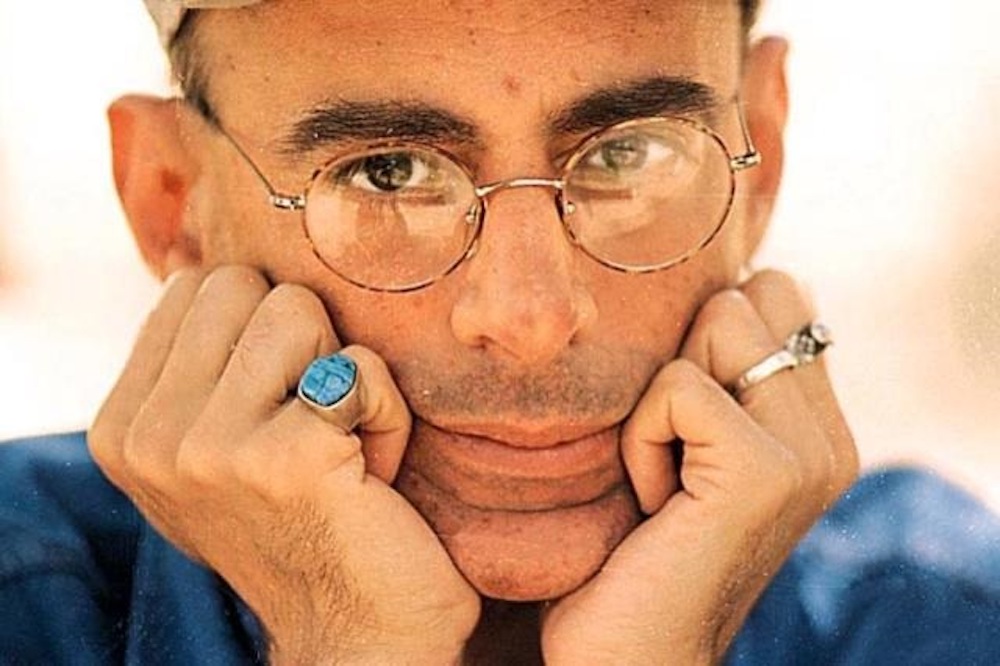

One of the most influential and original Brazilian writers of short fiction of the eighties and nineties, Caio Fernando Abreu is the author of several story collections set and published during the military dictatorship and the AIDS epidemic in Brazil. He has been awarded major literary prizes, including the prestigious Jabuti Prize for Fiction a total of three times. He died of AIDS in Porto Alegre in 1996. He was forty-seven years old.

Ed Moreno is a writer and translator from Santa Fe, New Mexico. He is a Lambda Literary Fellow and the recipient of a Bread Loaf Translators’ Conference scholarship. His work has appeared in Words without Borders, the Nashville Review, Foglifter, Blithe House Quarterly, and Cleis Press’s “Best Gay” series. He is currently writing his first novel.

“Three Letters for beyond the Walls,” by Caio Fernando Abreu, translated by Ed Moreno, excerpted from Cuíer: Queer Brazil published by Two Lines Press, 2021, as part of the Calico series. Reprinted with permission from the estate of Caio Fernando Abreu and Ed Moreno.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3kQ9U8g

Comments

Post a Comment