This year, I suggest a sad and lovelorn Halloween, tender and tolerant of monsters. The book for the mood is the 1816 novel Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley (1797–1851), a classic of gothic literature whose pages inspired foraged-fare acorn scones, a cocktail, and a bread pudding—not weird science, but foods of love.

Readers, critics, and biographers have long sought the key to Frankenstein in Mary Shelley’s life, which had all the tragedy and plot twists of a good gothic novel. Shelley was the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft, author of the early feminist text A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, and William Godwin, a radical political writer as famous as Wollstonecraft in his time. When Mary was sixteen, she fell for a young poet on the make, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and ran off to France with him, along with her fifteen-year-old stepsister, Claire Clairmont, who also later had a sexual relationship with Shelley. The ménage ran out of money and returned to England, but stayed together, perennially short of cash and living according to the principles of free love. Their conduct ostracized Godwin despite his radical reputation, and most of Mary’s circle of friends.

Frankenstein asks “Who shall conceive the horrors of my secret toil, as I dabbled among the unhallowed damps of the grave?” Making scones was much more pleasant.

Mary began work on Frankenstein a few years later, when she was still in her teens, on another trip to Europe. One fateful rainy afternoon, a group that included Mary, Percy, and Lord Byron dared each other to write scary stories. The others never followed through, but Mary’s story would become perhaps the most famous result of a parlor game ever produced. The book is composed in nested points of view, letters and stories within stories, a structure that was popular at the time and is particularly elegant for Frankenstein because the layers make the wild contents feel more plausible. It follows the conventions of gothic literature, exploring themes of fear, exile, and loneliness, and begins in a frozen wasteland, with letters from a young sea captain describing a perilous mission to the far north. There, the sea captain meets Victor Frankenstein, once a promising young scientist, whose “heart overflowed with kindness and the love of virtue” but who had “committed deeds of mischief beyond description horrible, and much, much more.”

Frankenstein’s crime was to have stitched together a giant man from the parts of other men and endowed it with life. When the ecstasy of conception is over, he is horrified by his creation, which has a “dull yellow eye” and a “shriveled complexion,” and moves with “convulsive motion.” He flees from it, but the creature eventually pursues him, and murders, one by one, his family members and loved ones. In the morality of the book, the retribution is partially a condemnation of scientific overreach, but is more a consequence of Victor Frankenstein’s lack of appreciation of what it means to be a human being. When the monster confronts Victor and reveals its point of view, we learn that it felt itself to be “a poor, helpless, miserable wretch” and that it longed for companionship. In this context, Victor’s abandonment of it upon its birth was cruel.

There is nothing cruel about bread, cream, onions, herbs, and cheese. Recipe from A Gothic Cookbook, by Ella Buchan and Alessandra Pino.

The monster demands that Victor make it a female companion—and promises that if he does so, it will do no further harm. Its words are moving:

If you consent, neither you nor any other human being shall ever see us again. I will go to the vast wilds of South America. My food is not that of man; I do not destroy the lamb and the kid, to glut my appetite; acorns and berries afford me sufficient nourishment. My companion will be of the same nature as myself, and will be content with the same fare. We shall make our bed of dried leaves.

Victor fails to honor this romantic request, and brings about his own downfall. One lesson of Frankenstein is that what matters in life is not our accomplishments but how we treat each other, which must have had special resonance for the author, given her personal circumstance of love and exile. The stitched-up green corpse, in this reading, becomes an object of tenderness, a person we should all do better by.

A page from A Gothic Cookbook, with acorns collected for me by my mother and illustrations by Lee Henry. The cookbook will include a recipe on how to make acorn flour.

I was inspired to write about Frankenstein when I came across A Gothic Cookbook, by Ella Buchan and Alessandra Pino, a project currently in the funding stage from the London-based publishing company Unbound. Buchan and Pino were able to share the introduction to their chapter on Frankenstein and several of their recipes, which reflected the creature’s choice to sustain itself on found and foraged vegetarian foods. Percy Shelly was a vegetarian, as was Lord Byron, and the creature’s vegetarianism, they write, “becomes a symbol of his inherent goodness.” They made an acorn bread inspired by the creature’s diet of acorns, and a bread pudding made up of the components of a shepherd’s breakfast that the creature eats after it has unfortunately scared the breakfast’s owner away. They also shared a recipe for a green-hued Corpse Reviver 1818 cocktail from a drinks supplement to the cookbook, which is available to certain pledge levels.

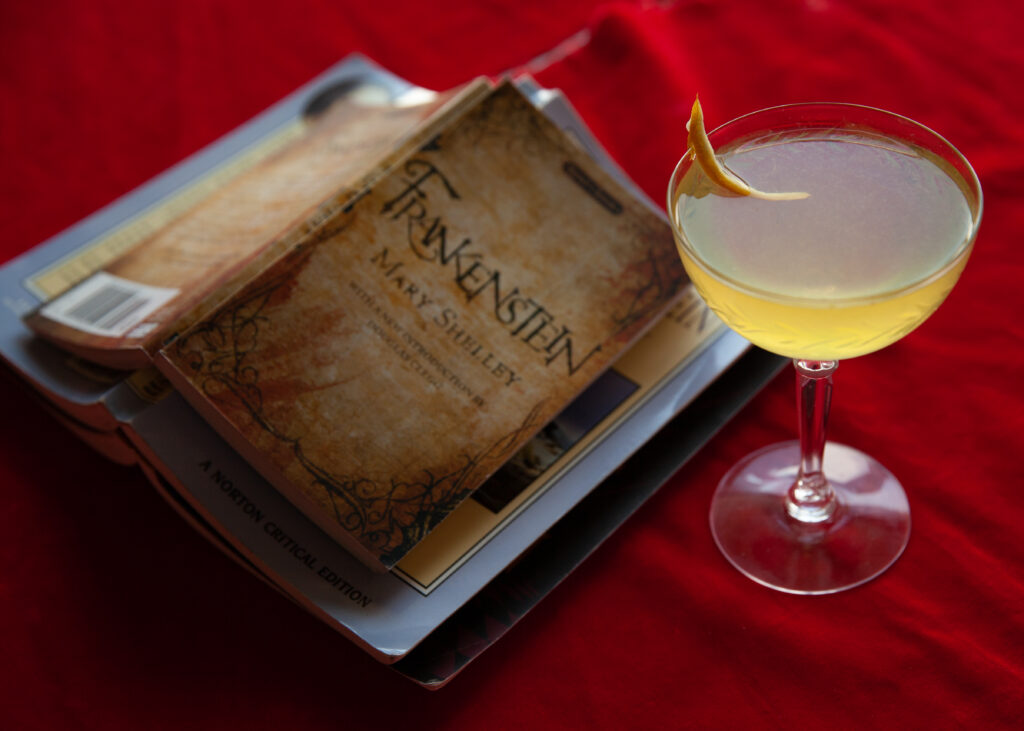

I planned to make the bread pudding, which sounded easy and delicious, and the cocktail, which miraculously asked only for alcohols I already had on hand. I also wanted to include a dish made from items I could forage myself, and settled on apple scones made with acorn flour (both are in season). If Victor Frankenstein had been merciful and created a wife for the monster, the wife would have been in luck, because these foods were amazing. The Corpse Reviver 1818 is made with gin, Chartreuse, vermouth, lemon juice, and a few drops of absinthe—appropriately green and strange for Halloween. The bread pudding was rich, herby, and crispy, and served as evidence that nothing can possibly go wrong with bread, onions, cheese, and cream. My foraged scones tasted like gingerbread, and showed that a diet that does no harm can also be highly rewarding.

One night, while foraging for food like these acorns, the monster also finds an abandoned portmanteau containing “Paradise Lost, a volume of Plutarch’s Lives, and The Sorrows of Werther.” Naturally, it devours them. Photo: Erica Maclean.

The first two dishes were easy, but the scones were more of a process. One challenge in making them was to incorporate apples, the seasonal wild ingredient available to me, in a way that wouldn’t make the final product too wet. I foraged super-ripe, spotty little red apples from a tree on my property in Vermont, then sliced them and dried them out in a two-hundred-degree oven for two hours, which made them surprisingly sweet and cutely miniature, as well as dry enough not to impact the scone texture. The second challenge was to make the acorn flour, a process that in truth I didn’t quite finish it in time, so I’ve used flour ordered online for the photos seen here. The scones with the store-bought acorn flour were toothsomely dry and pillowy, with tangy pops of flavor from the apples. I’ve since made the acorn flour at home, though I haven’t baked with it, and it was ridiculously time intensive but fun. I wouldn’t venture to offer a recipe, but I did learn how to crack acorns (a lot of bashing in a mortar and pestle); how to remove the toxic inner skin of acorns (freeze for twenty-four hours, then thaw, and it’s still not easy); and how to leach out the tannins from acorns (grind and then soak; mine took twenty-four hours). A fresh-cracked acorn is powerfully redolent of oak and is something everyone should smell at least once in their lives. The fully processed acorn flour is mild and little bit magical, with the faintest hint of vanilla and dried leaves.

It was not lost on me that to make these dishes required time, modern technology, and access to ingredients not found in the wild—mostly things the creature did not have, but which I had access to as a benefit of our shared human society. If the book’s message was to emphasize the value of that, it’s a good reminder for any holiday, including Halloween.

Corpse Reviver 1818

Makes one cocktail. Adapted from A Gothic Cookbook’s vintage-style cocktail booklet, available as a crowdfunding pledge level: https://unbound.com/books/a-gothic-cookbook/levels/12092/

Ingredients

1 oz dry gin

1 oz Lillet Blanc (you can also use white vermouth, though it will be drier/less sweet)

1 oz Chartreuse

A few drops of absinthe

1 tbsp of lemon juice

Lemon twist, to serve

Method

Fill a cocktail shaker with ice and add the spirits (you only need a little dribble of absinthe). Add the lemon and shake well. Strain into a chilled coupe or martini glass. Add a lemon twist, and enjoy!

Apple-Acorn Scones

6 small, sweet foraged apples

1 cup acorn flour (store-bought)

3/4 cup white flour

1 tbsp baking powder

6 tbsp sugar, divided

1/2 tsp salt

8 tbsp cold butter, diced

1/4 cup plus 1 tbsp buttermilk

1 egg

2 tsp ground cinnamon, divided

Make the dried apples. Preheat the oven to 200. Line a large baking sheet with parchment paper. Slice the apples as thinly as possible, place them in a single layer on the baking sheet, and bake until shrunken and dry, about two hours. Let cool.

Increase the oven temperature to 375. Mix together the acorn flour, white flour, baking powder, 3 tbsp of the sugar, and salt in a medium mixing bowl. Add the cold butter, and cut in with a pastry blender until the mixture is mostly combined and any remaining chunks of butter are smaller than pea-size. Make a well in the center, and add the egg and the buttermilk. Whip with a fork to combine, and then start pulling in the flour mixture, stirring until the entire mass is moistened. Use your hands to crunch the dough together until it is homogenous and forms a single ball.

Flour a work surface and roll the dough out to an 8 x 10″ rectangle. Sprinkle half of the rectangle with 1 tbsp of the remaining sugar, 1 tsp of cinnamon, and 1/4 cup of dried apples. Fold the dough in half, roll out again, and repeat the process with another 1 tbsp of sugar, the remaining 1 tsp of cinnamon, and another 1/4 cup dried apples. Fold again, but do not roll out.

Using your hands, crunch the folded dough into a roughly circular shape, scatter with dried apples, dust with the remaining 1 tbsp of sugar, and press lightly with your fingers to make the apples adhere. Place the dough on a baking sheet, cut it into six wedges, and pull the wedges apart a little so they don’t stick together when they cook. Bake for seventeen minutes, until puffy and cooked through.

Shepherd’s Breakfast Bread Pudding

Adapted from A Gothic Cookbook, by Ella Buchan and Alessandra Pino.

Ingredients

2 red onions, finely sliced

1 tbsp olive oil

3 tbsp balsamic vinegar

1 tbsp granulated sugar

1/3 cup of red wine

1 medium loaf of day-old or slightly stale bread, sliced

4 tbsp unsalted butter, softened

2 tbsp chopped fresh herbs (thyme, parsley, and rosemary work beautifully)

100g hard cheese, grated (we used 50/50 cheddar and Gruyère)

1 cup whole milk

2 eggs

1 cup heavy cream

1 tsp Dijon mustard

3/4 tsp salt

Pepper to taste

Make the caramelized onions. Heat the olive oil over a medium heat, add onions, and sauté for a few minutes, or until soft. Add vinegar, sugar, and wine, increase heat and cook until the liquid has evaporated and the onions are sticky. Season with salt and pepper.

Beat the softened butter with the herbs and a pinch of salt. Spread this mixture over each slice of bread, then quarter each one into triangles.

Preheat oven to 350 and grease a large baking dish. Arrange a layer of bread on the bottom, top with a layer of onions, and sprinkle with cheese. Repeat the layers until the ingredients are used up, ending with cheese.

Whisk together the milk, eggs, cream, mustard, 3/4 tsp salt, and pepper to taste. Pour over the bread, pushing down so it soaks up the liquid. Rest for five minutes then bake for 25-30 minutes, until puffy and lightly golden.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2ZA4fut

Comments

Post a Comment