What is our relationship to history? Do we belong to it, or is it ours? Are we in it? Does it run through us, spilling out like water, or blood?

I think the answers to those questions, at least in America, depend upon who you are—or rather, on who you’ve been taught to believe that you are. If the history you descend from has been mapped, adapted, mythologized, reenacted, and broadcast as though it is the central defining story of a continent, perhaps you can be forgiven (up to a point) for having succumbed to a collective distortion.

But what if yours is a history the wider world once recorded not as lives and feats but as articles of inventory? Men, women, children listed according to their age and value as property? What if the largeness of those lives—what they endured, yes, but also what they carried, remembered, witnessed, and made—has been hushed up, negated, overwritten, or outright erased? What if the recovery of your full story sheds stark light on the lie of that other, louder story?

There it is: light. It took three paragraphs to creep in as a metaphor, though it runs through the work of Lucille Clifton like life force. Light comes to her. Light speaks. Light emanates from the figures of history and myth, like Lucifer—God’s bringer of light—whom Clifton claims as her namesake, and who in her rendering testifies:

illuminate i could

and so

illuminate i did

If light is what the work of Clifton is intent on spreading, then I’m tempted to think that history as we have been conditioned to accept it is unrefracted, all of a piece, and blindingly white. Whereas Clifton’s imagination is prismatic. It slows down the central story so we can see what it is truly made of: all the dazzling colors moving at different frequencies and, depending upon circumstances, in distinct directions.

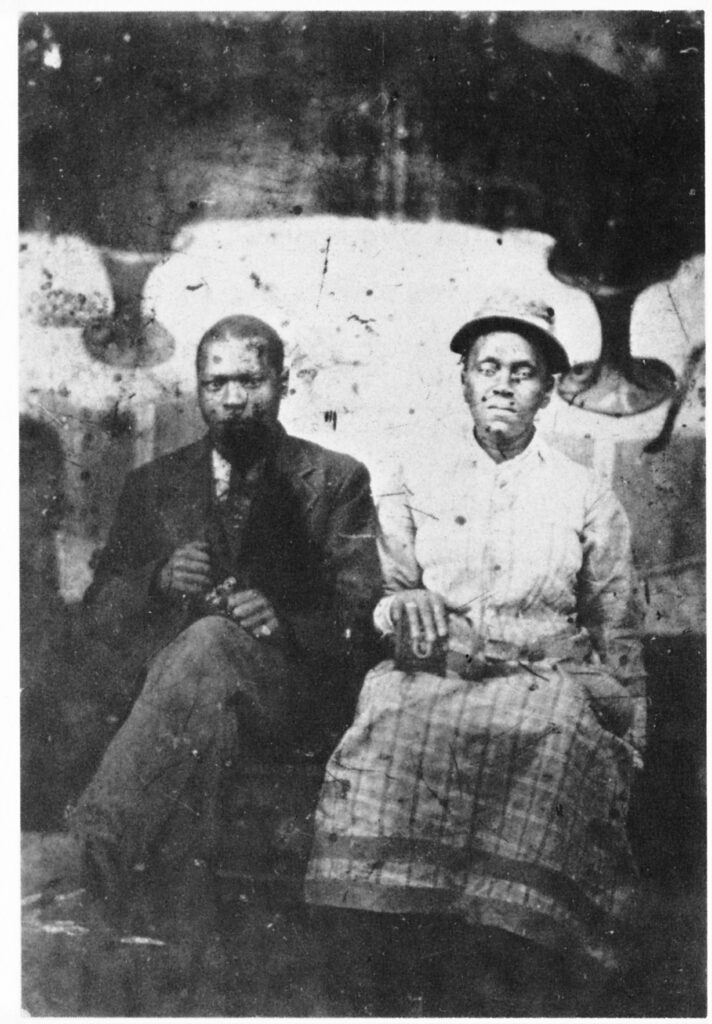

In Generations, her poetically terse and emotionally epic prose memoir first published in 1976, Clifton uses the occasion of her father’s funeral to attest to the lives lived and the marks made by the generations of people she descends from. First they are names, dates, and places. Like Caroline Donald—Mammy Ca’line—“born free among the Dahomey people in 1822 and died free in Bedford Virginia in 1910.” To reinscribe these lives into recollected history is to restore history itself to a rightful state of commotion.

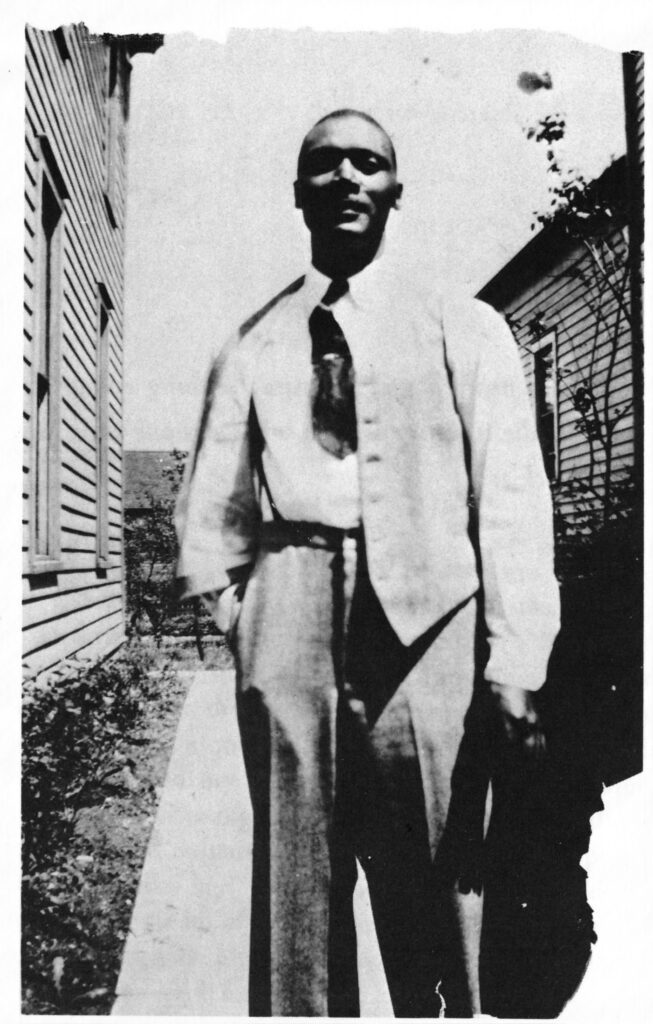

Once named, these kin arrive en masse, brought to life through the rhythm and inflection of voices—like the voice of Clifton’s own father, Sam Sayles, in whose vernacular rhythm Mammy Ca’line is not merely described but rather conjured:

Oh she was tall and skinny and walked straight as a soldier, Lue. Straight like somebody marching wherever she went. And she talked with a Oxford accent! I ain’t kidding. Don’t let nobody tell you them old people was dumb. She talked like she was from London England and when we kids would be running and hooping and hollering all around she would come to the door and look straight at me and shake her finger and say “Stop that Bedlam, mister, stop that Bedlam, I say.” With a Oxford accent, Lue! She was a dark old skinny lady and she raised my Daddy and then raised me, least till I was eight years old when she died.

I hear, in Sayles’s Ohs and his Lues and his exclamations and his insistence, something exultant and—positively—oracular. He is engaged not simply in an act of telling but of creating and consecrating a capacity for belief and understanding in both his daughter and—if we are listening properly—his daughter’s readers. The passage above segues seamlessly into the following capacity-expanding moment, when Clifton’s father signifies how, at eight years of age, Mammy Ca’line “walked North from New Orleans to Virginia in 1830,” at which point she was sold away from her family:

I remember everything she ever told me, cause you know when you that age you old enough to remember things. I remember everything she told me, Lue, even though she died when I was eight years old. And then I knowed about what she remembered cause that’s how old she was when she got here. Eight years old.

Mammy Ca’line’s depth of feeling, knowledge, and loss—in other words, the reality of her personhood—both affirmed and was affirmed by the reality of young Sam Sayles’s selfhood. As a child in grief, he found depth of feeling and knowledge, or generated it, through belief in what Mammy Ca’line, in her own grief, would have been required to find or generate.

These are the lives that America’s dominant history, as defined by aspirational notions of white personhood, has let fall into shadow. These are the stories that have been left unmarked and untended by America’s preferred view of itself, like the graves of slaves on land passed down through the white generations. One of the major contributions of Clifton’s writing is that she has teased out these lives, allowing them to demand their rightful space, to command our full attention, to teach us things about themselves and ourselves.

But it is not enough only to tease out, to separate and disband. Clifton’s purpose is to teach us to see that we are, in fact, moving together and that we are, in fact, part of a large whole. If that whole is unified, unity is not what we have been taught to believe; it is not compliance, not assimilation, not an enforced hierarchy. Neither is it simply escape. What, then, is the vision of America that Clifton is intent upon illuminating?

When you arrange one prism next to another, all those different colors—red, orange, yellow, and so on—rejoin one another, and together they begin to move in another direction.

I take it as significant that Clifton invokes Walt Whitman’s voice alongside the everyday poetry taken from the mouths of her ancestors. In this context, Whitman’s “Song of Myself” is no longer a familiar American music but an invitation to a radical reconfiguring of self. In other words, when Whitman’s “I celebrate myself, and sing myself, / And what I assume you shall assume, / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you” is sat beneath a portrait of Clifton’s grandfather and great-grandmother, what I am made to understand is this: here in America, and perhaps everywhere, no matter who we have been made to believe that we are, we are—all of us—the children of slaves.

Tracy K. Smith is a writer and former United States Poet Laureate. The author of a memoir, Ordinary Light, and four poetry collections, including Life on Mars, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2012, she is a professor of English and African and African American Studies at Harvard University.

From the introduction to Generations by Lucille Clifton, published by NYRB Classics. Introduction copyright © 2021 by Tracy K. Smith.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3AU8NsV

Comments

Post a Comment