Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re dreaming of other worlds, and highlighting writers of speculative and science fiction. Read on for Samuel R. Delany’s Art of Fiction interview, an epilogue chapter to Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea series, and Margaret Atwood’s poem “Frogless,” paired with photos from Richard Kalvar’s series “Earthlings.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Interview

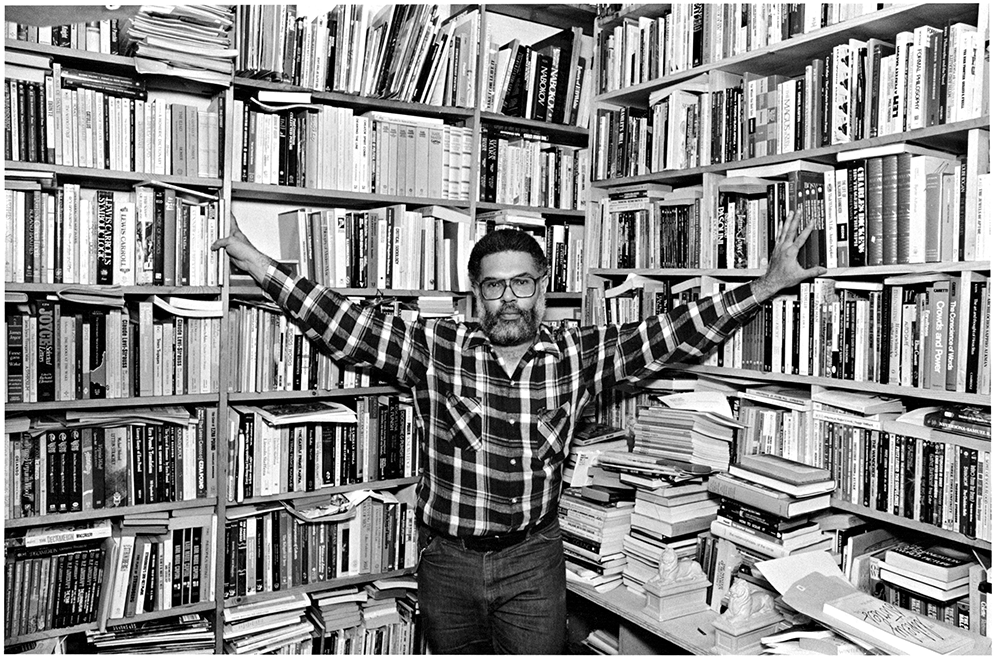

Samuel R. Delany, The Art of Fiction No. 210

Issue no. 197 (Summer 2011)

INTERVIEWER

Do you think of yourself as a genre writer?

DELANY

I think of myself as someone who thinks largely through writing. Thus I write more than most people, and I write in many different forms. I think of myself as the kind of person who writes, rather than as one kind of writer or another. That’s about the closest I come to categorizing myself as one or another kind of artist.

Fiction

Firelight

By Ursula K. Le Guin

Issue no. 225 (Summer 2018)

Were the mountains gone then, too, that other boundary, the Mountains of Pain? They stood far across the desert from the wall, black, small, sharp against the dull stars. The young king had walked with him across the Dry Land to the mountains. It seemed west but it was not westward they walked; there was no direction there. It was forward, onward, the way they had to go. You go where you must go, and so they had come to the dry streambed, the darkest place. And then on even beyond that.

Poetry

Frogless

By Margaret Atwood

Issue no. 117 (Winter 1990)

Here comes an eel with a dead eye

grown from its cheek.

Would you cook it?

You would if.The people eat sick fish

because there are no others.

Then they get born wrong.This is not sport, sir.

This is not good weather.

This is not blue and green.This is home.

Travel anywhere in a year, five years,

and you’ll end up here.

Art

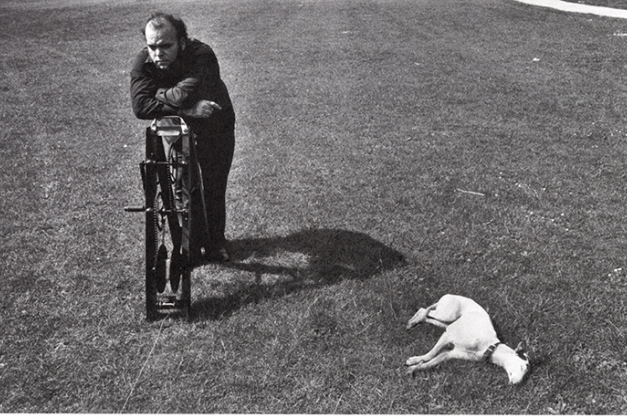

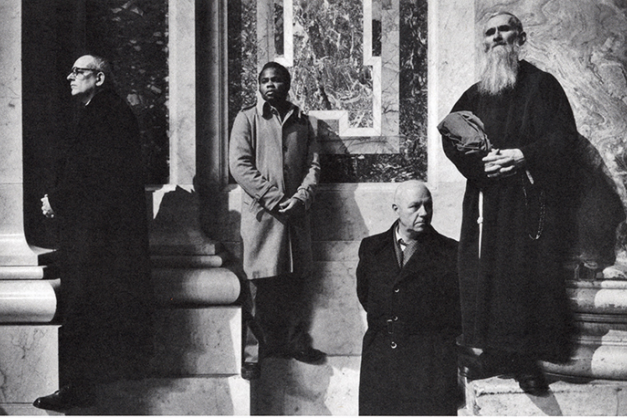

Earthlings

By Richard Kalvar

Issue no. 180 (Spring 2007)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3Ck21Om

Comments

Post a Comment