Yesterday, we launched Season 3 of our podcast, with an episode that includes Yohanca Delgado reading her story “The Little Widow from the Capital.” To mark the occasion, we asked Delgado what allows her to begin writing again when nothing else has worked:

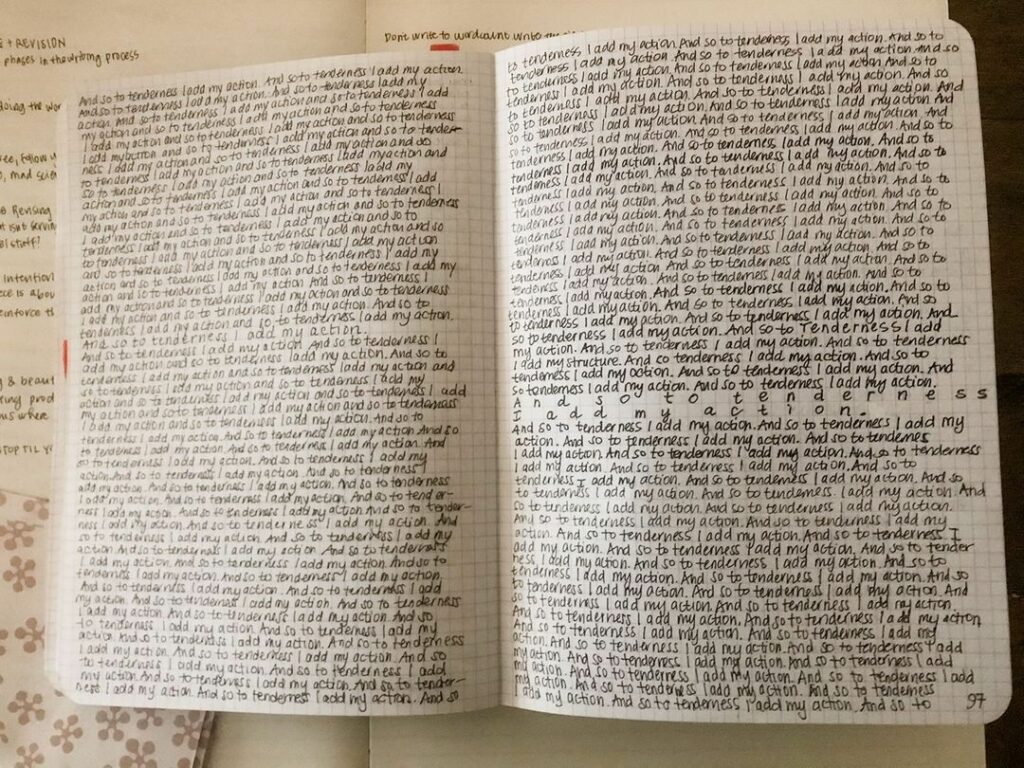

When I struggle to write, I shrink my expectations: two words a day. No more, no less. The part of my brain that seeks narrative shyly re-emerges. Maybe day one is easy: a first and last name. But even as I close my laptop, I don’t want to stop there. Beatriz Ortiz wants something. And word by word, the exposed brick wall in Beatriz’s office emerges, the smell of the tangerine she’s peeling…

It becomes an Oulipian exercise, a game of Pass the Story. In A Swim in the Pond in the Rain, George Saunders describes the construction of a story as a gradual process, in which different versions of the writer slowly build the best possible draft through small revisions. The version of me who has just watched Viy has access to a different set of narrative links than the version of me who has just re-read a story from Christine Schutt’s Pure Hollywood or Nafissa Thompson-Spires’s Heads of the Colored People, or who has just spent an hour googling “is shrink-wrap recyclable.” Each day, a version of myself floats a decision about where the story might go, and I relearn that by putting one word in front of another, I can make my way to places I’ve never been before.

The episode also features conversations from The Paris Review’s Art of Poetry interviews with Antonella Anedda and Robert Frost, and it occurred to us that writers might seek counsel there as well.

ANTONELLA ANEDDA

I follow a sound or an image and then I jot down the words in a notebook or in the back of a book. I can and must write everywhere. I have a husband, a very old father, a very old aunt, a daughter. What I’m trying to say is that I cannot have “rituals” as I write. I work hard, as anyone must, but I take advantage of every time and place. I am at home in every moment of calm. I write, I read, I rewrite, I read again, I correct, I put up with my desperation, get through my desperation, get over my desperation. This all takes some time before moving on to the computer. I build up my courage, reread, make corrections. When I am exhausted, I deliver the poem.

ROBERT FROST

Very first [poem] I wrote I was walking home from school and I began to make it—a March day—and I was making it all afternoon and making it so I was late at my grandmother’s for dinner. I finished it, but it burned right up, just burned right up, you know. And what started that? What burned it? So many talk, I wonder how falsely, about what it costs them, what agony it is to write. I’ve often been quoted: “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader.” But another distinction I made is: however sad, no grievance, grief without grievance. How could I, how could anyone have a good time with what cost me too much agony, how could they? What do I want to communicate but what a hell of a good time I had writing it? The whole thing is performance and prowess and feats of association.

What it is that guides us—what is it? Young people wonder about that, don’t they? But I tell them it’s just the same as when you feel a joke coming. You see somebody coming down the street that you’re accustomed to abuse, and you feel it rising in you, something to say as you pass each other. Coming over him the same way. And where do these thoughts come from? Where does a thought? Something does it to you. It’s him coming toward you that gives you the animus, you know. When they want to know about inspiration, I tell them it’s mostly animus.

Listen now at theparisreview.org/podcast or wherever you get your podcasts. New episodes will arrive every Wednesday in November. And don’t forget to catch up on Season 1 and Season 2.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3mq2HMW

Comments

Post a Comment