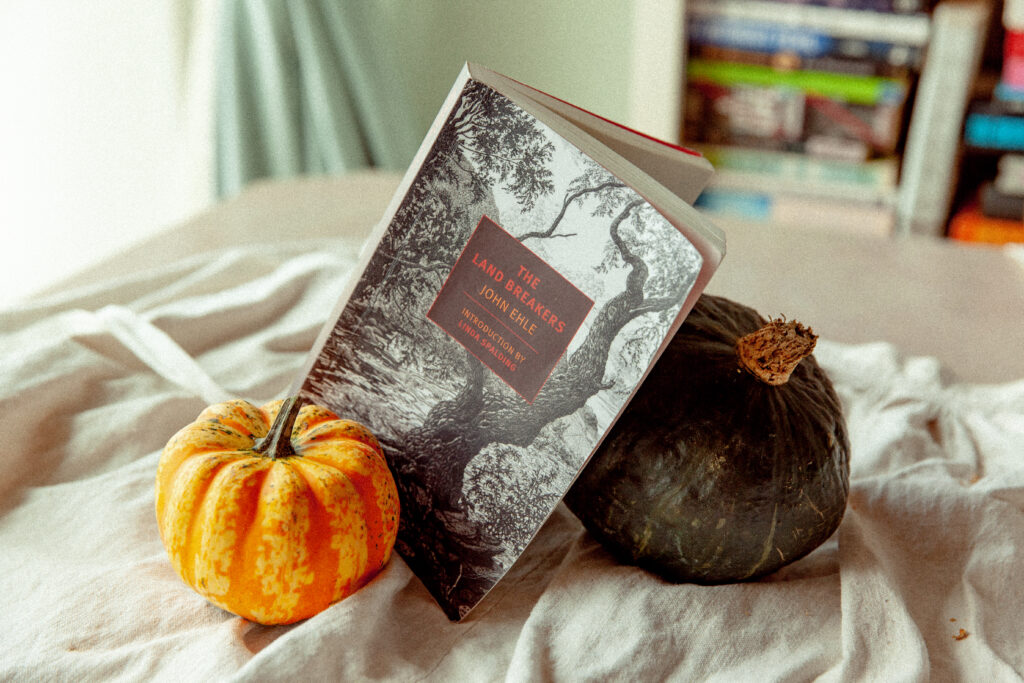

The Land Breakers, by John Ehle (1925–2018), the first in the author’s “Mountain Novels” series, is a story of America’s founding, set in the mountains of Appalachia and full of the hardscrabble food of the early settlements—wild turkey hen, deer meat, corn pone. These dishes are historically accurate, like Ehle’s work, but diverge from those traditionally associated with the early American table, at least those represented on holidays like Thanksgiving. Ehle’s novels depart from our traditional patriotic fare in more ways than one: they’re mythic, like all origin stories, but hold a broad view of who should take part in them, and honor the country’s origin without diminishing its moral complexity. To me his food suggested an opportunity for a better Thanksgiving, a project which also allowed me to make cornbread in a skillet, serve an entrée in a gourd, and offer an authentic recipe for buckeye cookies found nowhere else on the Internet.

The Land Breakers was published as a standalone work by New York Review Books in 2014. The story begins in 1779, with two former indentured servants, Mooney and Imy Wright, arriving at a chain of mountains that have been “left but lately” by the Native Americans. It reflects, to some extent, Ehle’s family history; the writer’s mother came from one of the first three families to settle the western mountains of North Carolina in the eighteenth century, according to the book’s introduction. That family history must have been oral to some extent and peopled by multitudes, because the book and the ones that follow it have a breadth of characters and an ornate, backwoods-vernacular prose style that brilliantly captures the time and place. The effect feels like a correction to some of the more sanitized versions of early American history (including ones I’ve previously cooked from). The books are worth reading for the dialog alone. In one snippet we learn that a man’s feelings “‘ain’t like a wart on his thumb, to be took off with ashes.’” In another, someone new to the neighborhood is told “‘…there was two nice new people last autumn, but they got et by snakes…’” A woman says she’s not finished making supper because the bread is not browned, “‘I ain’t served brownless bread yet, and I’m not going to take up shiftless ways.’” The voices are extraordinary.

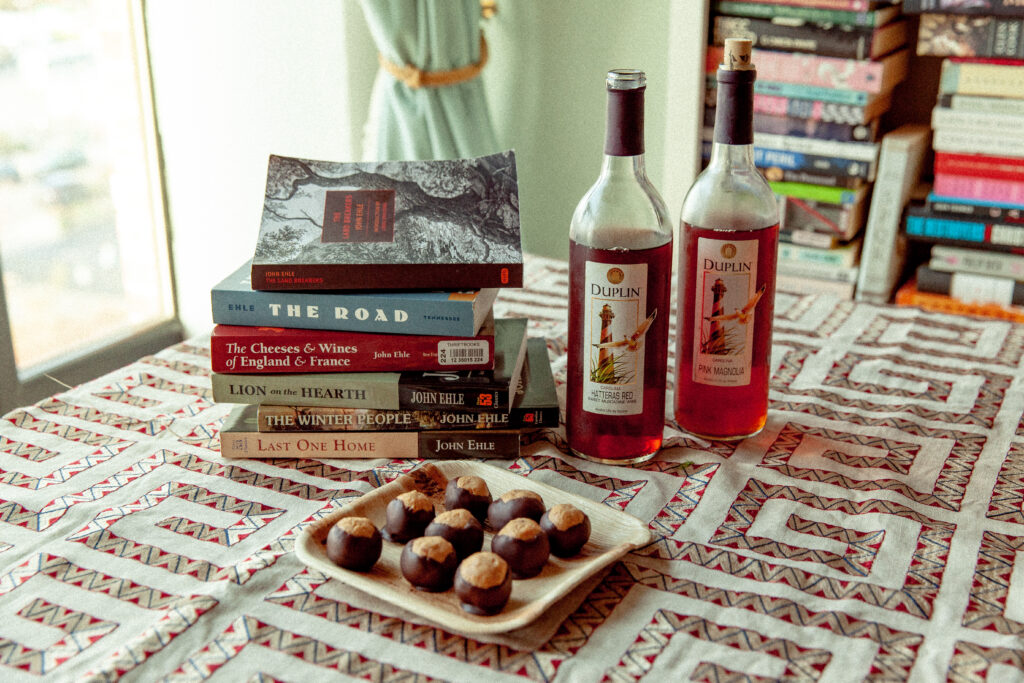

Ehle began his career as a writer of radio plays, and later married actor Rosemary Harris (their daughter is the actor Jennifer Ehle). In addition to writing novels and varied non-fiction works, he was an activist, working throughout his life for arts education, diversity in education, and anti-poverty initiatives, and spending two years as an advisor to the governor of North Carolina in the 1960s. Ehle’s nonfiction works include a book on the student civil rights protests at the University of Chapel Hill, published in 1965, and a book on the history of the Cherokee nation, published in 1988. A man of diverse interests, he also wrote a book on how to make French and English wines and cheeses at home.

Like some of the greatest Southern writers of the midcentury—he shares literary DNA with Faulkner and O’Connor—Ehle understood race to be a central feature of American life, and his novels include the full scope of peoples who were part of the American story. In The Land Breakers, enslaved people arrive in the story with the slaveowner Tinkler Harrison, the second settler to follow Mooney and Imy into the mountains, and while they aren’t major characters, their presence is one of the book’s moral poles. Connie, an enslaved woman who works as a midwife, curses Lorry on the birth of her child for the sin inherent to human nature. The curse seems unfair to Lorry, who is one of the book’s quiet heroes, and we’re forced to wonder if her sin is that she assumes she has rights over the land. In The Road, the second of the Mountain Novels, it’s primarily Black convicts who work and die on the railroad construction project that is the book’s setting. The white managers of the road project are the book’s heroes, but again Ehle complicates their accomplishment, linking the process of mastering land with the action of mastering people.

My buckeye cookies were inspired by a buckeye tree in the book, whose falling nuts, along with “acorns, beechnuts and chinkapins…rattled always across the forest floor.”

In Ehle’s fiction, his wideness of vision served a greater project: to show history as made by all types of men—the strong and virtuous, like Mooney Wright and his second wife Lorry; the greedy and prideful, like the slave-owning Tinkler; the ne’er do wells and music-makers, like Ernest Plover and his incredibly-named daughter, Pearlamina. These latter two do no work at all, and Pearlamina is a highlight of the book, precisely for her refusal to “break land” the way the others do. If the book frames the settlement project as a savage conflict between the men and the mountain, which is personified almost as if it were a character in its own right, it also understands the desire to live in peace with nature.

Ehle shines a bright light of humanism onto his characters’ lives, making them ask in their own words what their lives mean, and always finding different answers. There were so many of these passages that I began marking them when they occurred. One character thinks: “we are set not adrift as on a sea, for the sea supports whatever floats on it; we are adrift in the air and and move like dried leaves whisked about…” Another character, talking about his travels, says “the endless trails were like the patterns in a man’s life, always progressing but not going anywhere that could be predicted, yet pleasant.” For Mooney, work is the purpose of life, “[w]ork cutting and splitting until your strength was ebbing…go into the house and eat your supper, deer meat usually, a reminder always that the wilderness was close by, and bread made of new corn, and, of late, a piece of boiled cabbage.” The purpose of his work is to make a family and a home, another topic upon which Ehle excels. Few passages are more beautiful than Lorry’s reflections on the house she and Mooney make, where “they had come to be a family…safe unto itself, in a house that smelled of cooking and herbs and wool and wine vinegar, each one in its special season as the family made for itself comfort and protection.”

Apples appeared in the book, and lady apples are in season. I pickled them according to a recipe by celebrated Southern cooking chef Edna Lewis.

As is often the case in books that are concerned with farming and homes, The Land Breakers goes into great detail about food. The fare is gritty and poor in the settlement’s early days. In Mooney’s first encounter with Pearlamina, he says “‘I have some turkey meat….Got that and milk. Got an egg to eat.’” Pearlamina has nothing but herself to contribute, and makes Mooney “nervous and uneasy, lest she go away.” Later, Lorry wins Mooney with her steadiness, going to his house and leaving him a stew of the humble things: “deer meat…mushy with herb-cooking and brown gravy.” When he goes to her house for the next meal, she has only three potatoes to eat, but also some treasured salt which she has been hiding from her sons in a gourd. She brings it out for Mooney, who says gratefully, “‘I like salt better’n anything on a piece of meat.’” It’s a simple statement that tells much about the privations of settlement life.

For my menu, I skipped the turkey in favor of the deer-meat stew with herbs and gravy, enhanced with dried apples, as a nod to the bit of dried apple Mooney keeps in his shirt to disguise his scent while hunting deer. To decide which leaves to use, I drew from a passage that details the herbs and greens Lorry would forage for: “she would take to the paths and find sallet greens, find poke, cut young green shoots from the wild grape vines, pick leaves of herbs she knew were safe, blue root and dock, for example.” Sallet greens are any green used for cooking and might include sorrel or spinach. Poke is an oniony-tasting poisonous weed that grows in Brooklyn as well as Appalachia, where it’s boiled three times to remove the toxins and considered a delicacy. I’m fairly certain I see it in the summer on the bike path near my Brooklyn apartment. Wild grape leaves are available everywhere in my mother’s metro-Boston suburb. Blue root and dock both inspired rabbit-holes of internet research; the former might be gingery, the other is tart and lemony. I couldn’t forage out-of-season, but it was fascinating to realize how many of these items are available to me, even in the city. I worked ginger, onion and lemon flavors into the finished dish.

Served piping hot, this version of corn-bread is crunchy-chewy perfection. Adding butter and honey would be cheating.

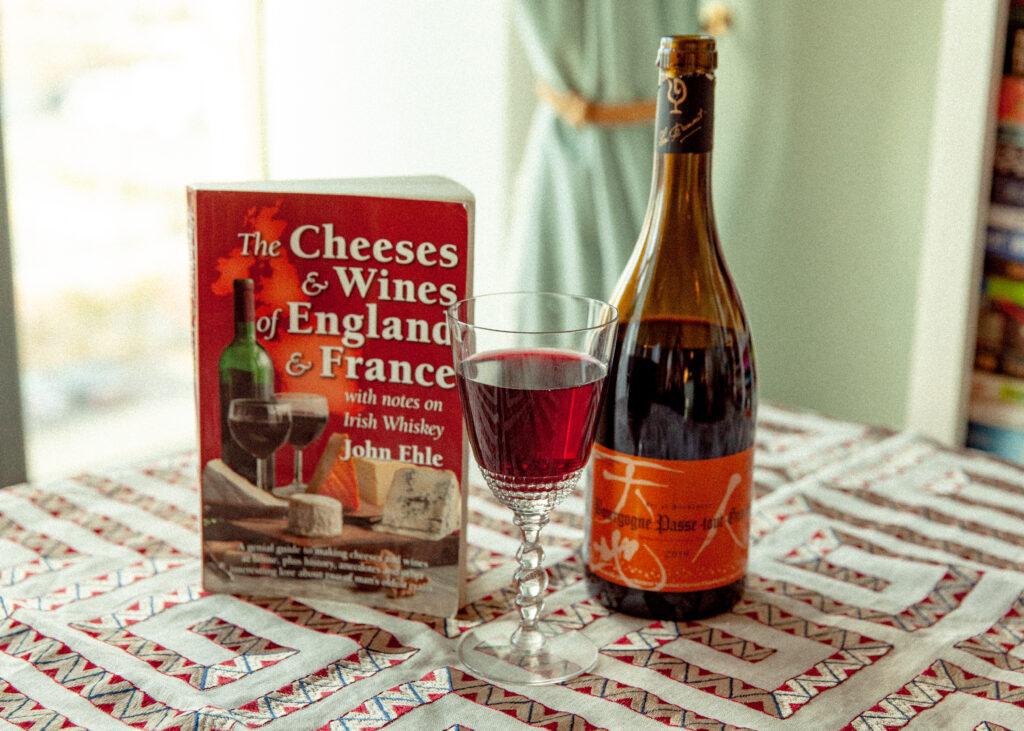

Cornbread is ubiquitous in the books, so I made a corn “pone,” an appropriately austere cornbread often made without eggs or milk. As the farms become more established and successful, Mooney slaughters a pig, and the characters are able to eat more lavish meals, like “fresh meat, field beans, and hot bread.” I re-created the field beans, which research indicates were string beans, and pickled them as Lorry does, with vinegar she has made from muscadine grapes. I did not make my own vinegar, but I did ask my spirits consultant, Hank Zona, for a Muscadine wine to serve with the meal, and he sourced me one from North Carolina, which came with the caveat that it was probably going to be “foxy” and sweet-tasting, and more geographically relevant than good with my meal. Hank also picked a Passe-Tout-Grains from Maison Lou Dumont in Burgundy, based on Ehle’s focus on the wines from Burgundy in his nonfiction work on wine and cheese. This particular type of Burgundy is unusual in that it’s a field blend of Pinot Noir and Gamay, and is more rustic than the region’s usual wines. Its style fit the interest Ehle shows in returning to traditional maker-culture in The Cheeses and Wines of England and France.

Ehle wrote about wines from Burgundy. I served a rustic option in an old-is-new-again style that was intensely flavorful but light-bodied, like my meal.

For dessert, there was an offbeat choice of my own, buckeye cookies. I’m told these are the official cookie of Ohio, not North Carolina, but Mooney and Lorry had a buckeye tree outside their house, which turns yellow in the fall, and drops “its eye-shaped seeds.” This moment in the novel, when Lorry is meditating on the beauty of the land around her, is one of my favorite passages. She concludes that “[a]utumn…in these lush, water-fed lands, was more colorful than springtime.” I love fall, too, and those dropping buckeyes made me crave a football-season standby that’s essentially a peanut-butter ball dipped in chocolate. A friend from Ohio shared his mother’s recipe with me, which is distinguished by adding graham cracker crumbs and shredded coconut to the peanut butter filling, making the buckeyes lighter and less sweet than usual.

My austerity foods were a revelation. The settlers had so few possessions that they often used dried-out gourds for dishware and storage. I served my venison stew in a roasted winter squash, accompanied by corn pone and pickled beans and apples. Mooney fell for Lorry because of these foods, and I understand why. My stew was incredibly savory and tender, and fresh thanks to the “foraged” greens. I ate the whole thing, while scraping out bites of the roasted pumpkin. This entree paired wonderfully with the crispy, light cornbread, the crunchy pickled beans, the sweet pickled apples, and the berries-and-spice profile of the Burgundy wine. If there was a relative lack of sugar, fat, starch and dairy on this table—all the things that make Thankgiving such a gut-bomb—I didn’t miss them. I thought my holiday meal was better than the traditional one, and whipped up easy, too.

I am a Lorry Wright type, so I suggest that readers run out and make my recipes instead of their planned Thanksgivings, dashing about town at the last minute for venison and individual-serving-sized winter squashes. But if you are more a Pearlamina Plover and plan to do no such thing, Ehle forgives you. He writes in his food book that he spends more time thinking about making wine and cheese than actually doing so, and suggests that “[i]f you do nothing more than daydream about making them, I will accept that, for even daydreams will help; daydreams are attitudes after all, and have influence.” These are the views of a man with a subtle and expansive view of history—and who sets a good table, too.

Pickling Spice

This recipe will be used for both the Spiced Lady Apples and the Pickled Field Beans.

1 tbsp: cinnamon chips, fennel seeds

2 tsp: crushed bay leaves

1 tsp: yellow mustard seeds, brown mustard seeds, coriander seeds, allspice berries, peppercorns, dill seeds, fennel seeds, cloves, celery seeds, juniper berries

½ tsp dried chili flakes

Spiced Lady Apples

Adapted from In Pursuit of Flavor, by Edna Lewis. You will need a 1 quart mason jar.

2 cups cider vinegar

2 cups white sugar

½ cup light brown sugar

1 tbsp pickling spice

1 cinnamon stick

3 cups lady apples

Put the vinegar and sugars into a large saucepan. Tie the pickling spices up in a piece of cheesecloth and add to the pot. Add the cinnamon stick. Bring to a simmer and cook gently for 15 minutes.

Wash the apples but don’t destem them. Prick them 3 or 4 times with a knife, and add to the pot. Simmer gently for 30 minutes more. When the apples are tender, remove the pot from the heat and let them cool. Transfer apples and syrup to a 1 quart mason jar.

Pickled Field Beans

You will need a 1 quart mason jar.

1 cup vinegar

1 cup water

2 tbsp sugar

1 tbsp salt

2-inch chunk of ginger

1 tbsp pickling spices

Two large handfuls of green beans

Combine vinegar, water, sugar, salt, ginger and pickling spices in a medium saucepan and bring to a boil. Turn off the heat and set aside to cool. Wash and trim the beans, and arrange them in a mason jar so they’re all standing up and neatly aligned. Stuff in as many as you can; they’ll shrink a little in the liquid.

Set a large pot of water on to boil. Blanch the beans in the water for 30 seconds, then shock them to stop them from cooking in a bowl of cold water with ice. Return the beans to the jar. Add the cooled liquid, cover and refrigerate at least several hours before use.

Corn Pone

2 cups cornmeal

1 tsp salt

1 1/2 cups water

4 tbsp bacon grease or neutral oil

Combine cornmeal and salt in a medium-sized bowl. Add water and stir to combine. Let stand for 2 hours (if time allows), to allow grains to soften and soak up liquid. Add bacon grease or oil to a 9-inch cast-iron skillet. Set the oven to preheat to 475, and put the skillet in so it gets hot. Remove the skillet from the oven and pour in the batter, using a spoon to baste the top with the oil that bubbles up along the sides. Bake for 15-minutes until brown and crispy on the sides. Set the oven to broil for the last 2-3 minutes to brown the top. Let cool before slicing.

Venison Stew Served in a Gourd

Serves 2. This recipe requires an overnight marinade.

2 medium-small winter squashes

1 lb venison stew meat

1 cup buttermilk

4 scallions, chopped

1 cup corn flour

3 strips bacon

3 tbsp neutral oil, as needed

1 tsp minced ginger

1 tsp dried thyme

½ cup dried apples

3 cups water

4 cups washed, chopped greens; I used a mixture of dill, watercress and spinach

Salt and pepper to taste

Prepare the venison by cleaning thoroughly, removing every scrap of membrane and silver skin (essential for the venison to be tender). Cut into 1-inch pieces, add scallions, buttermilk and 1 tsp salt, cover and refrigerate overnight.

On the day you plan to serve the meal, preheat the oven to 400. Cap the squashes and scoop out the seeds. Increase the size of the opening, if necessary, in order to make the squash “bowl” shaped. Rub the insides with olive oil, and season with salt. Place on a roasting pan, and roast for 40 minutes to 1 hour, until the interior is soft and the walls of the squash are visibly softened. Remove and reserve.

Remove the marinade from the refrigerator and allow it to come to room temperature. Cook the bacon in a medium-sized dutch oven. Remove bacon and reserve for another use (alternatively you can crumble it over the finished dish). Leave the grease in the oven; you’ll be using this to make the stew. Remove the venison from the marinade, shaking off excess moisture. Place the cornflour on a plate and season lightly with salt. Dredge the venison pieces in cornflour, shaking off any excess flour.

Reheat the Dutch oven (with the bacon grease) to medium-high, adding more oil as necessary if your bacon did not release much fat. Brown the venison pieces in batches, turning so that all sides are evenly browned. This is where you develop flavor, so take your time. When all the venison is browned, return it to the pan, add the ginger, dried thyme and dried apples, ½ tsp salt, and stir to combine. Add 3 cups of water, cover and bring to a boil. Uncover, turn down to a simmer, and cook for 1 hour to 90 minutes, until the stew is thickened and the meat is tender. Add the fresh greens and stir until wilted. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Ladle into a roasted squash, and serve.

Buckeye Cookies

Makes 25 cookies.

1 cup smooth, good-tasting peanut butter, no sugar added

4 tbsp unsalted butter, softened

1 tsp vanilla

½ cup crumbs from McVitie’s Digestives biscuits, ground

½ cup coconut flakes, fine

1 ½ cups powdered sugar

8 oz good-quality baking chocolate, 90-percent cacao

In a stand mixer, cream the peanut butter and butter until combined, using the paddle attachment. Add the vanilla, biscuit crumbs and coconut, and mix to combine. Add the powdered sugar and mix again. The mixture will be stiff and a little bit crumbly, but should adhere if you roll a ball of it between your hands.

Line a cookie sheet with parchment paper. Roll the peanut butter mixture into balls about 1-inch in diameter, place them on the cookie sheet, and freeze for 10-20 minutes until ready to use.

Chop the chocolate coarsely, place in a microwave-safe bowl, and microwave for 1 minute. Stir, then continue to microwave for 30 second intervals, stirring each time, until the chocolate is melted.

Remove the peanut butter balls from the freezer. Spear with a toothpick and dip the ball in the chocolate, rolling the bottom and sides to create the “buckeye” effect, and placing the dipped ball back on the cookie sheet. When they’re all dipped and the filling has softened slightly, you can use your finger to smooth over the hole from the toothpick. Store in the refrigerator.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3cHs9Ys

Comments

Post a Comment