|

In the late fifties, Stephen Sondheim, who died last week aged ninety-one, performed a song from the not-yet-finished musical Gypsy for Cole Porter, on the piano at the older composer’s apartment. As Sondheim recalls in Finishing the Hat, his mesmerizing and microscopically annotated first collection of lyrics, Porter had recently had both legs amputated, and Ethel Merman, the star of Gypsy—in which Sondheim’s words accompanied music by Jule Styne—had brought the young lyricist along as part of an entourage to cheer him up. Sondheim played the clever trio “Together.” “It may well have been the high point of my lyric-writing life,” he writes, to witness Porter’s “gasp of delight” on hearing a surprise fourth rhyme in a foreign language: “Wherever I go, I know he goes / Wherever I go, I know she goes / No fits, no fights, no feuds, and no egos / Amigos / Together!”

That fourth rhyme–it astonishes every single time–exemplifies everything I revere in Sondheim. He is, of course, a musical-theater god: from West Side Story through Company, Follies, Sunday in the Park with George, and Assassins, his influence trounces superlatives. Even his flops were often revelatory. Merrily We Roll Along proceeds backwards, anticipating by decades the experiments with time in shows like Jason Robert Brown’s The Last Five Years; The Frogs, a reimagining of Aristophanes first performed in Yale University’s swimming pool, must surely have been among the inspirations for Mary Zimmerman’s water-based stage adaptation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Wordplay is never just a pyrotechnic aftereffect in Sondheim’s shows—it’s foundational, crucial to the plot and the characters’ emotional development. And his work continually reminds you that playfulness (in poetry, in music, in lyrics, in visual art) can be most essential when the subject is deadly serious. Sondheim includes a multiple-choice quiz in a love song—“Now/Later/Soon” from A Little Night Music: “(A) I could ravish her / (B) I could nap”—and likewise in a paean to the uses of a gun, sung from the rotating points of view of the actual and would-be assassins of U.S. presidents: “Remove a scoundrel / Unite a party / Preserve the Union / Promote the sales of my book.”

The Sondheim lyrics I love are too abundant to list, but there’s one in his fairytale extravaganza Into the Woods that gets my personal gasp of delight. In the prologue to that show, Sondheim introduces the lyrical and musical motifs of each of the main characters. Full disclosure: I played Rapunzel in my high school’s production; don’t ask me to attempt her high B-flats anymore. Jack’s mother, trying to coax milk from their aging cow, Milky-White, grumbles to Jack that “We’ve no time to sit and dither / While her withers wither with her.” That triple homonym—”withers wither with her”—delights the ear, develops the mother’s character, and moves the plot forward, all at once. (Sondheim’s repetitions are always ingenious: “Then you career from career to career,” he writes in “I’m Still Here,” Carlotta’s torch song from Follies, which my grandmother memorably rewrote to celebrate leaving her job as a middle-school principal—rather an awkward choice for one’s own retirement party, perhaps, but I like to think Sondheim would have understood.) When Jack goes to market and trades the cow, whose meager supply of milk will no longer support them, “for beans”—an idiom that usually means “for nothing”—his mother, a literalist, gets furious again. Jack tells her that these are magic beans, worth far more than their beast, which it turns out they are.

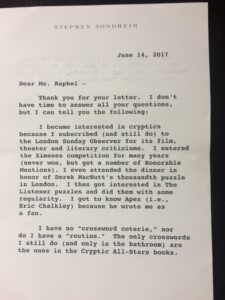

The high point of my own writing life was receiving a typewritten note from Stephen Sondheim. My weakness for that fourth-rhyme effect may be what first drew me to crossword puzzles, so it didn’t surprise me to find out that Sondheim liked them too, but while researching a book on the subject, I learned that he was also a brilliant composer of the cryptic crossword. Crossword lovers tend to remember their first eureka moment with a puzzle: that time they got stumped on a clue, only to realize they’d been seeing it the wrong way. “Strips in a club?” for example, indicates not dancing on a stage but BACON in a sandwich.

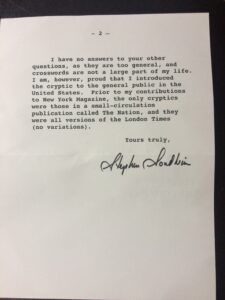

Unlike those in American-style crosswords, cryptic clues involve an extra layer of wordplay. In 1968, Sondheim began publishing cryptic crosswords in New York magazine, and wrote about them with reverence: “A good clue can give you all the pleasures of being duped that a mystery story can. It has surface innocence, surprise, the revelation of a concealed meaning, and the catharsis of solution.” He scorned the simpler American variety with equal relish: “The kind familiar to most New Yorkers is a mechanical test of tirelessly esoteric knowledge: ‘Brazilian potter’s wheel,’ ‘East Indian betel nut’ and the like are typical definitions, sending you either to Webster’s New International or to sleep.” I wrote to Sondheim’s agent, asking far too many questions; I edited and re-edited my letter and, after mailing it, spent the night in a cold sweat that I’d used the wrong grammatical tense. When Sondheim, to my astonishment, wrote back, he said that although he no longer had a regular solving practice, he counted introducing American readers to cryptic crosswords among the great achievements of his life. He’d given them a source of delight, a new way of seeing the world.

Crosswords initially appealed to me as a diversion, and I got hooked on them through that gasp of delight, but eventually I realized that they have special resonance in times of crisis. The crossword was invented in 1913, on the eve of World War I, when people craved something comforting in the newspaper. The New York Times first published its crossword during World War II, just after Pearl Harbor, to offer readers a distraction from the bleak headlines. Crosswords also leaped in popularity during the pandemic—I wrote two for The Paris Review in spring 2020—and not only because so many of us needed something to do in isolation. Crosswords provide an experience of immersion, yet they don’t completely shut out the world around you. Wordplay, whether in the best puzzles or in Sondheim musicals, can estrange your surroundings and the language through which you interpret them, allowing your life to catch you by surprise again.

Adrienne Raphel is the author of Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures With Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them, What Was It For, and the forthcoming book of poetry Our Dark Academia.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3Ib0ptC

Comments

Post a Comment