This past summer, I kept turning to a certain kind of prose: the diaries in Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook, the biomythography of Audre Lorde, Elias Canetti’s journals, the field notes of the British psychoanalyst Marion Milner. It seemed to promise me something, but what? The writing sometimes felt unpolished, as if the authors were allowing me to watch them work through a problem. It dealt with obsession, disappointment, depression. It wasn’t an obvious choice for the subway.

This past summer, I kept turning to a certain kind of prose: the diaries in Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook, the biomythography of Audre Lorde, Elias Canetti’s journals, the field notes of the British psychoanalyst Marion Milner. It seemed to promise me something, but what? The writing sometimes felt unpolished, as if the authors were allowing me to watch them work through a problem. It dealt with obsession, disappointment, depression. It wasn’t an obvious choice for the subway.

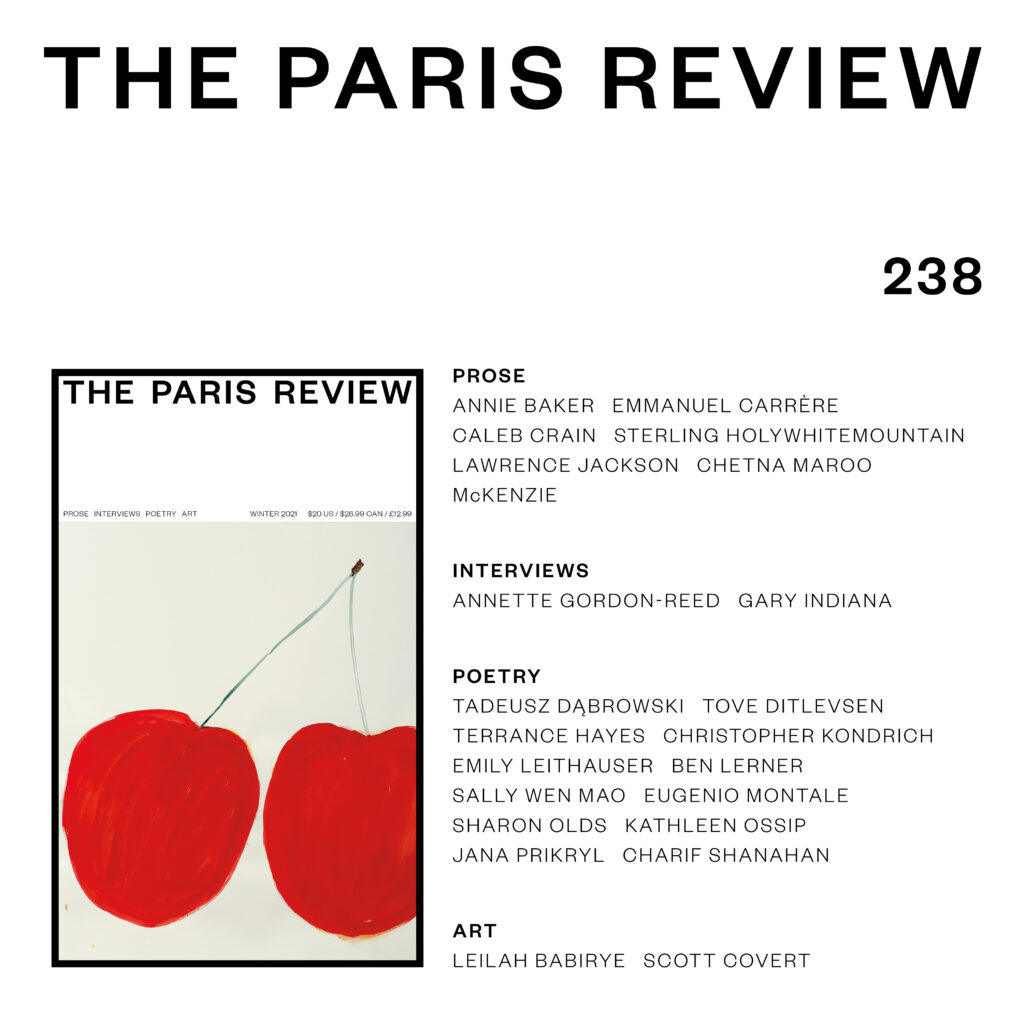

I had just started editing The Paris Review, a literary quarterly with a formidable sixty-eight-year record of publishing the best writing, and of hosting glamorous parties. Every morning, in the office, I made coffee under the gaze of a bronze George Plimpton, one of the founding editors. The space was dominated by a monumental bookshelf that housed an archive of past issues. The overall effect was beautiful, and a little forbidding. And yet, when I took down the first issue, I couldn’t help but notice that it was rather small, like a pamphlet. It featured William Styron’s famous manifesto for the Review, in which he writes that the new quarterly should emphasize work not by critics but by “the good poets and the good writers, the non-drumbeaters and the non-axe-grinders.” But even that piece of writing was less grandiose than I had remembered, irreverently presented in the form of a private letter, a set of notes to a committee of editors struggling to make a public statement.

When I first encountered the Review as a teenager, I had only the vaguest sense of its history. What I liked were the interviews with famous writers, conducted by younger ones seeking to learn. They seemed to offer an unprecedented form of access. I had assumed that the purpose of a magazine was to equip you with something usable, to help you to follow what other people were talking about. The Paris Review was not that sort of publication. Over the years, it provided the reading list I really wanted, one that privileged mischief, strangeness, and pleasure: Jane Bowles, Raymond Carver, Lydia Davis, Akhil Sharma, Morgan Parker.

In keeping a distance from criticism and the debates of the day, the Review has always created a space for something more intimate, for the writing that makes us feel that we are in proximity to another consciousness. This is what my colleagues and I have been after these past months, and what we will continue to seek, whether in work by established, lesser-known, or very new writers, in English or translation, in poetry or prose, in very short stories or very long ones, in fiction or nonfiction or something in between.

Our new Winter issue is launching online today, and it will be available on newsstands later this month. (If you are a current subscriber, it may have already reached your mailbox, or certainly will soon.) As you may know, it looks a little different from the issues of recent years, though some longtime readers will recognize the new design as a kind of return. Our designer, Matt Willey, was inspired in part by the issues of the seventies. These issues were printed on soft pages; their spines crack in the places where they are most often opened. They are small enough to hide in a big coat pocket, or to hold in one hand while reading on the subway or in bed.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3rLHFeB

Comments

Post a Comment