Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

When we at the Review first read Sterling HolyWhiteMountain’s story “This Then Is a Song, We Are Singing,” which is published in our new Winter issue, we found ourselves in thrall to the story’s narrator—who, for all of his rage and confusion, self-justification and delusion, is undeniably charismatic. Inspired by the pleasure we took in spending time in his company (at least on the page), we hunted through the archives for some of the most memorable—which is to say, memorably off-kilter—voices the Review has published over the years. Inevitably, this led us to our Art of Fiction interview with Marguerite Young, whose hallucinatory novel Miss Macintosh, My Darling is, in her words, “an inquest into the illusions individuals suffer from.” From the same issue, no. 71 (Fall 1977), there are two poems by Erica Jong in which a lonely narrator putters around, talking to her cat. We’ve also been sucked into John Edgar Wideman’s stream of consciousness in “Sightings,” and fascinated by the inscrutable portraits of Llyn Foulkes.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, poems, and portfolios, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Interview

Marguerite Young, The Art of Fiction No. 66

Issue no. 71 (Fall 1977)

It was the unconscious that interested me. I say that I am not interested in people, but I am interested in the bizarre and in people at an edge. I am interested in extreme statements about people because that is where drama is most apparent.

Fiction

Sightings

By John Edgar Wideman

Issue no. 171 (Fall 2004)

You can’t inch closer to what’s unreachable even when it’s pissing in your face. No pilgrim has returned and reported how it feels to die. That’s the dirty joke hunters go to the mountains to laugh at. Werewolf with other werewolves, furry clothes, furry faces, stomachs bloated with jelly doughnuts and beer.

Poetry

Two Poems

By Erica Jong

Issue no. 71 (Fall 1977)

I am a corpse who moves a pen that writes.

I am a vessel for a voice that echoes.

I write a novel & annihilate whole forests.

I rearrange the cosmos by an inch.

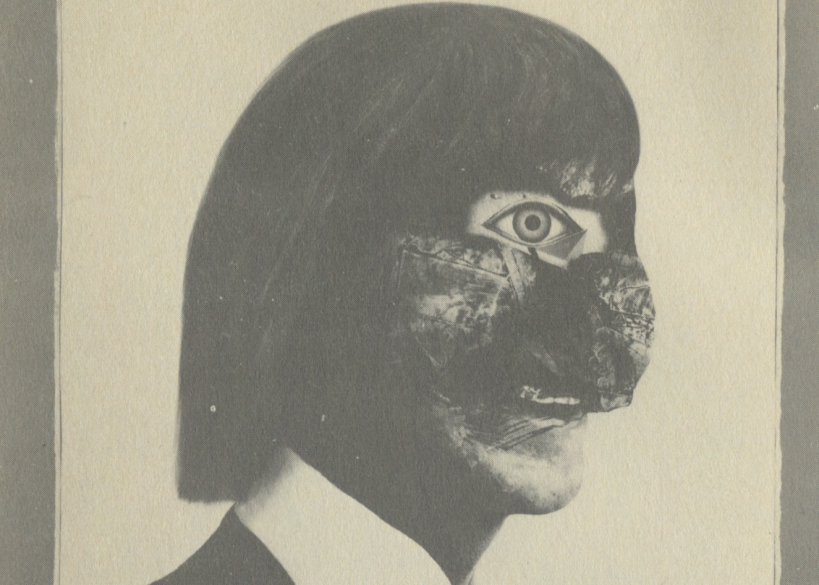

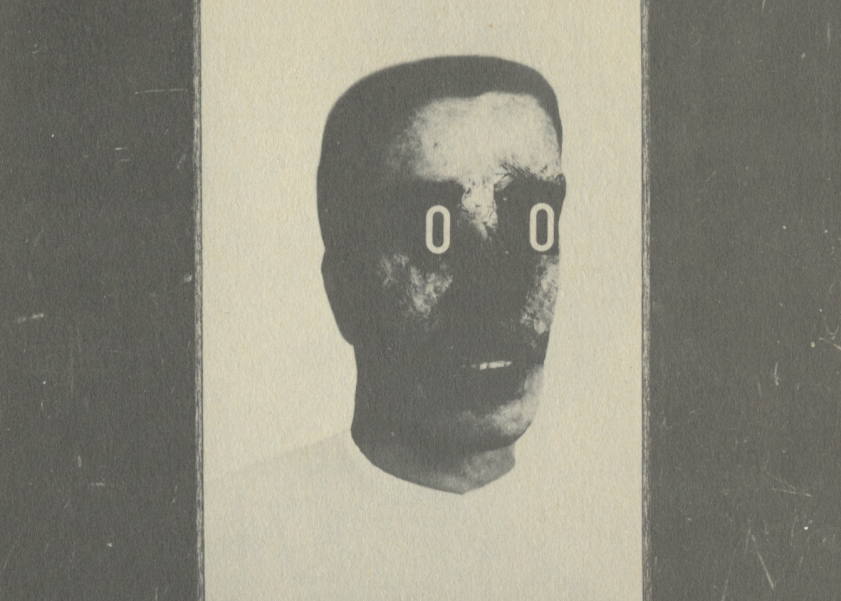

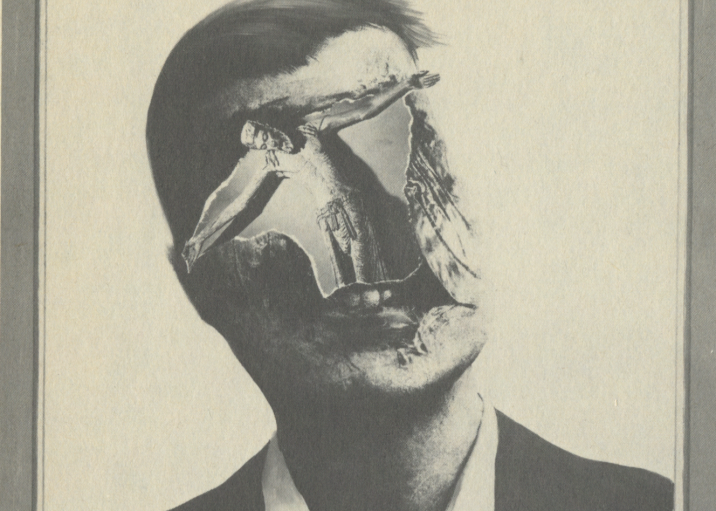

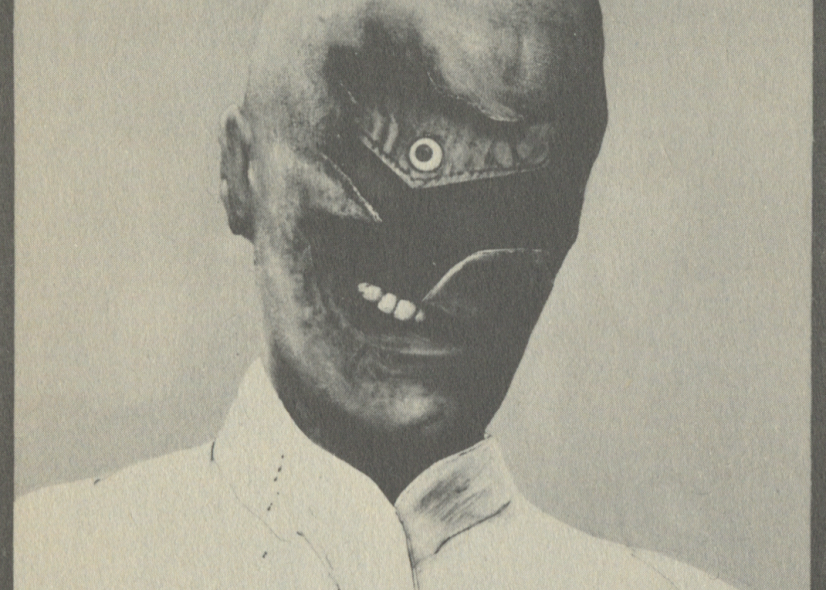

Art

Portraits

By Llyn Foulkes

Issue no. 100 (Summer-Fall 1986)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3pqJpsl

Comments

Post a Comment