Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

In a new essay published on The Paris Review Daily, the Chilean writer Alejandro Zambra explores how a lifetime of cluster headaches led him to seek relief in the hallucinogenic mushroom teonanácatl. He learns an important lesson: always wait before redosing.

In the spirit of experimentation, this week’s Redux riffs on writing under the influence. Read on for Hunter S. Thompson’s hard-won advice about which drug a writer should avoid, in the Art of Journalism No. 1; a hazy afternoon in J. M. Holmes’s “What’s Wrong with You? What’s Wrong with Me?”; Anne Waldman on the body as “just a bundle of drugs” in “How to Write”; Allen Ginsberg’s 1966 letter to the editor, regarding his experiences with LSD and psilocybin; and a portfolio of Nancy Friedemann’s loopy text-based drawings, as well as a sculpture.

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, poems, and portfolios, why not subscribe to The Paris Review? You’ll get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Interview

Hunter S. Thompson, The Art of Journalism No. 1

Issue no. 156 (Fall 2000)

INTERVIEWER

How do you write when you’re under the influence?

THOMPSON

My theory for years has been to write fast and get through it. I usually write five pages a night and leave them out for my assistant to type in the morning.

INTERVIEWER

This, after a night of drinking and so forth?

THOMPSON

Oh yes, always, yes. I’ve found that there’s only one thing that I can’t work on and that’s marijuana. Even acid I could work with. The only difference between the sane and the insane is that the sane have the power to lock up the insane. Either you function or you don’t. Functionally insane? If you get paid for being crazy, if you can get paid for running amok and writing about it . . . I call that sane.

Fiction

What’s Wrong with You? What’s Wrong with Me?

By J. M. Holmes

Issue no. 221 (Fall 2017)

The room was streaked with haze like we dropped cream in a coffee, but Rolls never cracked windows. He smoked like a pro even still, burned blunts and let it box out the room. He had the leather furniture from his dad’s old office and we sank into it. These days, he got lit every morning before work, after his bowl of Smacks. His latest was shooting an ad for the ambulance chaser Anthony Izzo. I was about to ask him if he still painted.

Poetry

How to Write

By Anne Waldman

Issue no. 45 (Winter 1968)

A lot of drugs can change you if you want

because you too are made of what drugs are made of

In fact you are just a bundle of drugs

when you come right down to it

Nonfiction

Footnote to Allen Ginsberg Interview, Issue #37

By Allen Ginsberg

Issue no. 38 (Summer 1966)

To readers of Paris Review:

Re LSD, Psylocibin [sic], etc., Paris Review #37 p. 46: “So I couldn’t go any further. I may later on occasion, if I feel more reassurance.”

Between occasion of interview with Thomas Clark June ’65 and publication May ’66 more reassurance came. I tried small doses of LSD twice in secluded tree and ocean cliff haven at Big Sur. No monster vibration, no snake universe hallucinations. Many tiny jeweled violet flowers along the path of a living brook that looked like Blake’s illustration for a canal in grassy Eden.

Art

New Work

By Nancy Friedemann

Issue no. 158 (Spring–Summer 2001)

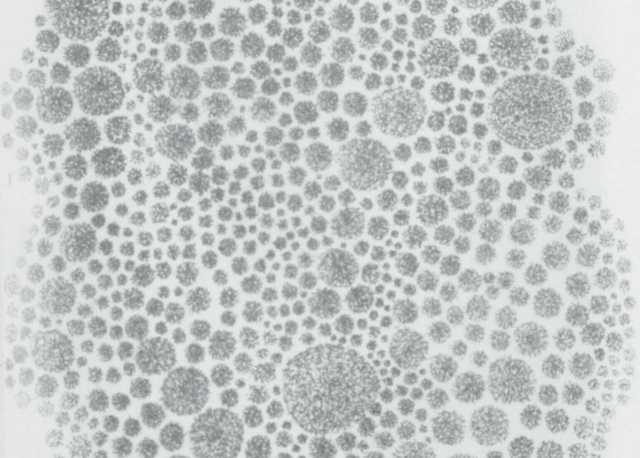

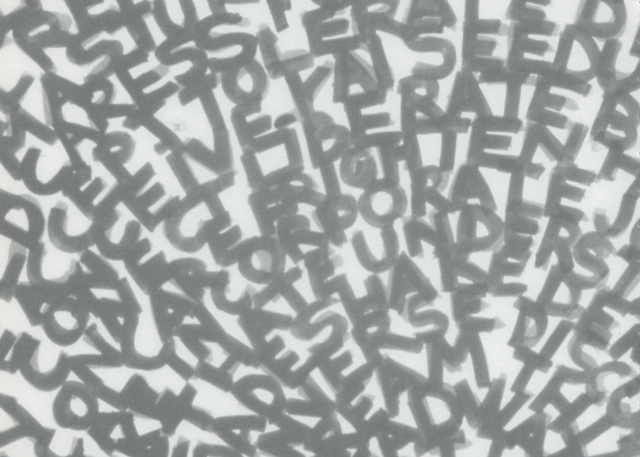

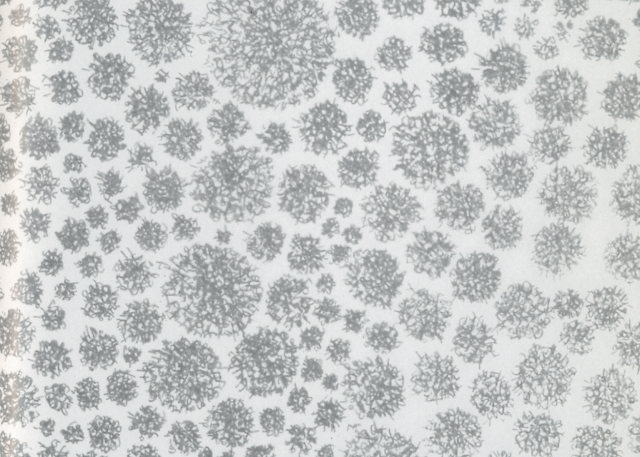

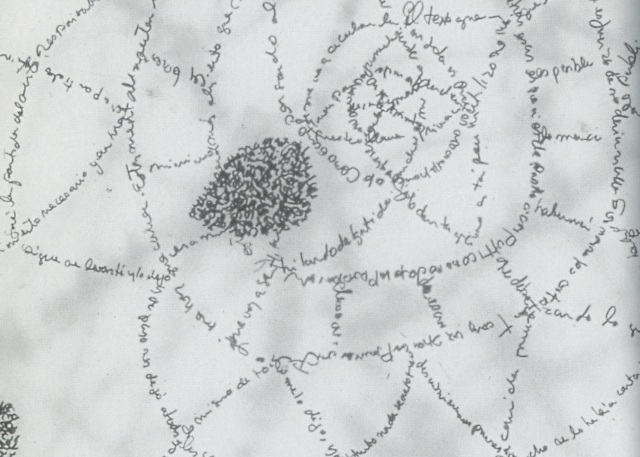

Last year I had the chance to watch Colombian-born artist Nancy Friedemann work in her studio at the artists’ colony Yaddo in Saratoga Springs, New York. Amidst a scattering of fat permanent markers—the kind graffiti artists use on subway interiors—various books lay sprawled on the floor, but otherwise the room was clean and spare: just eight four-by-six-foot panels of semitransparent vellum-like Mylar on the walls.

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3H5MLqW

Comments

Post a Comment