Illustrations by George Wylesol.

Teonanácatl. That’s what the Aztecs used to call the mushroom known today as pajarito, or “little bird.” My friend Emilio recommended it as a treatment for my cluster headaches, and he got me a generous dose in chocolate form. I stashed the squares in the fridge and awaited the first symptoms with resignation, though I sometimes fantasized that the mere presence of the drug would keep the headaches at bay. Sadly, soon enough I felt one coming on, and it was the very day we had planned a first-aid course. My wife Jazmina and I had just had a child, and after attending a clumsy, tedious introduction to first aid, we’d decided to call in a doctor, and ended up inviting other first-time parents to an exhaustive four-hour program that would take place at the house next door. But in the very early dawn of the designated day, I woke up with that intense pain in the trigeminal nerve that for me is the unequivocal sign of an imminent headache. My wife proposed that I forget about the course and stay home to take pajarito.

At four in the afternoon, Jazmina left with our son, Silvestre, and I devoured the first square, prepared for a brief, utilitarian trip. The chocolate was delicious, and I now think that that must have influenced my decision, after an impatient twenty-minute wait, to eat a second square. This time the effect was almost instantaneous: I felt hands reaching into my head to turn off my pain, like someone rearranging cables or dexterously pressing the keys on a safe. It was a delightful, glorious sensation.

I don’t want to get into too much detail about the misery this illness has caused me over the course of more than twenty years. Suffice it to say that my headaches came roughly every eighteen months, and their corrosive company lasted between two and four months, during which the idea of cutting off my head started to feel reasonable and efficient. Occasionally some medication or other allowed me to control or rather tame the pain, but none had ever brought the miraculous results I felt from this little bird. Teonanácatl—I should have mentioned before that the word means “flesh of the gods”—radically cleansed me. Of course, there was still the risk that the pain could return, but somehow I knew it wouldn’t, that I would be safe for a long time (eleven weeks and counting).

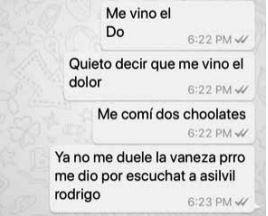

That was more or less the moment when I got it into my head that my friend Emilio was actually my son. I was convinced, but at the same time the idea was hard to accept. Still, in retrospect it was a pretty reasonable association: Emilio doesn’t suffer from cluster headaches himself, but he grew up watching his father, the children’s author Francisco Hinojosa, struggle with them for decades. If I didn’t manage to get better, my son would eventually grow accustomed to my migrainous periods, just as Emilio had to his father’s. I felt a light sadness, like the Bossa nova kind. I thought about how generous Emilio was, just as Silvestre would be in a few years. I imagined my son at twenty years old, telling a friend about his father’s awful headaches. I pictured Emilio, or rather I focused my imagination on his face, specifically his bushy beard. I resolved to shave him, and I did: first slowly, realistically, meticulously, with an electric shaver, and then with a lot of foam and a stupendous straight razor, even dabbing on some aftershave. I wanted to text him. I wrote:

I started to get a

Hea

I men I started to get a headache

I ate two choolates

Now my hear doesn’t hurt bt I listening to silvio rodrigo

Then the doorbell rang several times. I’m aware that there are probably families for whom ringing the doorbell in bursts is considered pleasant, but my family is not one of them. When I peered out the window, my annoyance turned to consternation, because it was Yuri down there—the person who had just rung the doorbell in that idiotic way was the famous Mexican singer Yuri, who, when she saw me leaning out the second-floor window, yelled: “I don’t have cash for the taxi and this prick’s waiting!” Teetering on heels that could easily pass for stilts, Yuri struck me as forceful, brave, and admirable. Imperiously, she shouted her demand for money again; I had a five-hundred-peso bill, too much for a taxi, but I tossed it out the window to her anyway. She nimbly scooped it up and the driver handed her change; Yuri stashed it cheerfully in her bag and left without a goodbye.

I don’t remember thinking that Yuri’s presence might be a hallucination. I don’t remember doubting her identity. Why was I so sure—why am I still so sure—that that little moocher was the singer Yuri? As I was making my way toward the bedroom (our apartment is very small, but my sense of space had shifted), I did have the thought that Yuri’s husband was Chilean and an evangelical Christian, and that perhaps to Mexican eyes we looked alike. There’s no doubt I look Chilean, but maybe I also look evangelical—I have the face of an evangelical Chilean, I thought. That’s when I became aware, though without making any connection to the preceding events, that I was high.

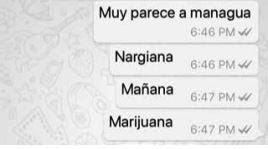

My shock soon gave way to a giggling that sounded a bit false, diplomatic, bureaucratic: it was as if I were laughing because I was supposed to, or to prove myself capable of articulating laughter. And, like someone traveling on business who comes out of a long meeting and realizes he finally has several hours free to explore the city, I felt a desire to make the most of my trip, or rather I felt obligated to want to make the most of it. But since the purpose of my drug-taking had been sadly therapeutic, I was unprepared for enjoyment. In a fit of pretentiousness, I considered writing something in a lysergic key. I also tried to read—there were several books on my bedside table—but it wasn’t easy with my eyes so fuzzy. I fumbled around, earnestly and unsuccessfully, for my glasses. I texted Emilio again, looking for advice or maybe just attention:

Its a lit like marinara

Narigiana

Marimba

Marijuana

I meant that the effect was similar to that of marijuana, though I’m not sure that’s really what I thought—it was more just a conversation starter. Emilio called me, and when he heard the high version of my voice he laughed, but was also alarmed. He told me that half a chocolate square would have been enough to extinguish the pain. I told him how I had shaved him but he didn’t understand, or maybe he thought I was using a Chilean expression. He asked where Jazmina and our son were. I told him they’d gone to a first-aid class, and he couldn’t believe it—he inferred that my wife, on seeing me in this condition, had decided to go right out and take that class. It sounded like an illogical or extraordinarily inefficient reaction on her part: something like dealing with an earthquake by reading a study on earthquakes. I explained the situation, and he felt better. I said I was hungry and was going to order something from Uber Eats. He told me to call him if I needed anything at all.

Aware of the impending munchies, I ordered food galore. My purchase included tacos al pastor, brisket tacos, chorizo and pork tacos, steak and smoked meat volcanoes, a fig tart, and three extra-large cups of horchata. I amused myself by watching the Uber map on my phone, and it seemed like Rigoberto’s bike was moving unusually fast. I thought, Rigoberto is going to kill himself, and I felt a faint shiver as I pictured hundreds of cyclists, their backpacks adorned with the Uber Eats or Rappi or Cornershop logo, stoically crisscrossing Mexico City.

Illustrations by George Wylesol.

I heard the doorbell—a brief, prudent, almost coy little ring. I didn’t think I’d be up to walking down the stairs. I sat on the top step and devised the brilliant plan of going down on my butt. After a period that seemed like half an hour I reached the bottom, and then I clung scrupulously to the wall like a Spider-Man in training. By the time I managed to get the building’s front door open, Rigoberto was long gone. Later I realized he had called me and my phone was in my pocket, but I’d never heard it or felt it vibrate. I went up the stairs in the same inelegant but safe manner I’d come down. The fog was spreading in my eyes; I felt I was in the middle of a dense cloud. I tried to look for my glasses again but was simply incapable. Then I discovered I was wearing them. I had been wearing my glasses this whole time. When I took them off I found that I could see fine, or as well as my astigmatism and myopia usually allowed me to see. I interpreted this “change” as a sign of normalcy, but I was wrong. I dragged myself to the kitchen and devoured everything I could find: some dismal slices of cheddar cheese, a bunch of rice crackers, several handfuls of uncooked oatmeal, three Chiapas bananas and two Dominico ones, and a few dozen arduous pistachios.

When I made it back to the bedroom, pretty desperate by now, I thought of Octodad, that agonizing and Kafkaesque video game where an octopus tries to coordinate his tentacles to carry out human activities. I’ve only played it once, but I haven’t forgotten how hard it was for Octodad to, say, pour a cup of coffee or mow the grass or buy groceries. I lay on the floor like a ball of yarn and thought about Silvestre, and I wished someone would take me by the hands and walk me to where he was. I thought about my son learning to crawl. “There are some children who never crawl”: that sentence arose in my head, spoken in the voice of a friend. “Some children just start walking right away.” Specialists emphasize the importance of crawling for neurological development, but there are also people who claim that those specialists exaggerate. I remembered a friend of Jazmina’s telling us about a university professor with impeccable credentials who had a student over to her house and crawled during the entire visit. I mean: she crawled to open the door, accompanied her guest to the living room crawling, crawled to get a glass of water for her, and only after some small talk—made on all fours—explained to the flabbergasted student, with utter solemnity, that she had decided to spend three days crawling, because she hadn’t crawled as a baby and wanted to rectify that disadvantage once and for all. We had cracked up over that story, which now struck me as very sad or serious or at least enigmatic.

So without further ado, I decided to try to crawl. I managed to plant my elbows securely but not my knees, and then nailed my knees but not my elbows. This happened several times. I turned over repeatedly on the floor, remembering how I’d rolled down sand dunes at the beach as a child. I lay on my back and managed to drag myself over the floor with my heels, in a kind of inverse crawl. I lay on my belly again and tried using my toes and elbows, but I couldn’t move forward: a slug would have beat me in a hundred-centimeter sprint. Then I realized, or discovered, that I had never crawled as a baby. I’d asked my mother about this recently on the phone. “I’m sure you did. All children crawl,” she said. It bugged me that she didn’t remember. She remembered that I learned to talk very early (she said this as though referring to an incurable disease) and that I started walking before I turned one, but she didn’t have a memory of me crawling. “All children crawl,” she told me, but no, Mom: not all of them do. Crawling is, in and of itself, elegant, I thought, but so is not crawling—to get up suddenly, à la Lazarus, and simply walk, with spontaneous fluidity, without any visible learning process. To walk without having crawled is an admirable triumph of theory.

Illustrations by George Wylesol.

Then I went off on a tangent and found myself analyzing the song “La cucaracha” with some rigor, and it seems to me now that I thought I was understanding something about myself or about Silvestre or about life in general, something impossible to relate yet true, definite, and even measurable. I pictured Silvestre at eighty years old. I thought, with indisputable sadness, I won’t be at my own son’s eightieth birthday party, because by then I’ll be… But I was not capable of adding eighty plus forty-three. I thought about the ending of The Catcher in the Rye. I thought about a story by the Chilean writer Juan Emar. I thought about these beautiful lines by Gabriela Mistral: “The dancer is dancing now / the dance of losing what she was.”

I jumped from image to image with the speed of someone reading only the first sentence of each paragraph. I wanted to sleep, I tried hard to fall asleep, but I had both feet planted firmly in the waking world. Then came an awful moment when I heard voices crying out for me, I knew I had to run over to the house next door, that they needed me there, but I couldn’t and I felt utterly useless, I was utterly useless. I saw myself as a building whose windows were all smashed. I saw myself as a deflated yoga ball. I saw myself as a giant snail drooling slime on the floor where everyone would slip and slide. I heard the voices of my wife, my son, calling to me, and with a practically heroic vestigial reserve of energy, I managed to stand up and take a couple of steps before falling on my ass.

I lay aching on the floor and closed my eyes for several minutes. I wasn’t sleepy, but I knew I still had the capacity to sleep. And I did. The next thing I remember is that I felt better. Or rather, I thought I felt better, but I also mistrusted my feelings, so I started taking inventory, awakening my senses. I ventured a careful, timid crawl. My knees hurt a lot, which, maybe because of my Catholic upbringing, I interpreted as a positive sign. I reached the living room and stayed on all fours looking at the plants. Some beautiful ants, the blackest and shiniest and danciest ants in all of human history, were coming and going along a little path that began at a groove in the window and ended at the summit of a flowerpot. I looked at them intently: I absorbed them, I enjoyed them. I said something to them—more than one thing, I don’t remember. I concentrated on the plants. I called them by their names, recently learned: succulent, bromeliad, oleander.

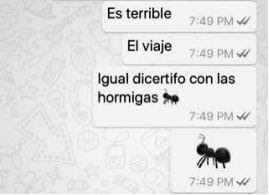

I wrote this message to Jazmina; I felt better:

This trip

is terrible

But I’m enfoying the ants (ant emoji)

(ant emoji)

At a certain point I discovered it was dark out and that I could move with some degree of normalcy. The first-aid class must have been about to end, or maybe it was already over. I considered the possibility of doing nothing. I almost never consider that possibility. Instead, I decided to take some little excursions between the bedroom and the living room—I didn’t even think about the Charly García song, “Yendo de la cama al living”—practicing for my expedition to the house next door. I went on a lot of excursions. Judging by the time of the next message, which I sent to Jazmina immediately before going outside, I practiced for over an hour:

Finally I felt confident I would not take a nosedive. The fresh nighttime air on my face was a blessing. I idealized the imminent scene, eagerly anticipating or foreseeing Jazmina and Silvestre, and I imagined that they coincided, that they were once again a single person. But the first thing I saw when I opened the door was disconcerting: a group of adults crawling on the ground.

For a fraction of a second I thought I was still mid-trip, or that they had all taken pajarito, too, or that it wasn’t a class on first aid but rather on crawling. One of the crawlers, perhaps the most diligent, was Jazmina. When she saw me she got up, hugged me, and explained that the class was over but they’d spent the past hour looking for the doctor’s cell phone. Silvestre was asleep in his grandmother’s arms. I kissed him and wanted to pick him up, but I held back, just in case. I joined the group of crawlers with ambition and bravura—Now this I can do well, I thought—moved by a competitive, vindicatory desire to be the one to find the doctor’s phone. I ran into my friend Frank under the table, and he looked bored, or maybe remorseful. He told me, in English so no one would understand (though I think everyone there understood English), that the doctor was making too big a deal out of this.

Illustrations by George Wylesol.

The doctor did, in fact, seem disproportionately dejected: she was crawling around like a baby searching for her most treasured rattle. Then she stood up and leaned against a window in a melancholy pose. She looked at the ceiling and shook her head like someone trying, for the umpteenth time, to remember a name or an address or a prayer. The scene seemed to drag out forever, unbearably: fifteen or twenty minutes of the doctor mourning her lost cell phone.

Cold milk is recommended to cut a trip short, but at that moment I was sure the doctor needed it more than I did. She accepted the glass I handed her with apparent bafflement. Then came the sudden denouement, which was obvious, categorical, slapdash: Frank had accidentally stashed the damned phone at the bottom of a diaper bag. My friend gave the doctor a contrite, mischievous smile, but she wasn’t having it: solemnly and professionally she drank her glass of milk, and then she left. We all left.

I picked up Silvestre and started humming a very fast version of Yuri’s song “La maldita primavera.” Jazmina was laughing and yawning. We walked home with sure steps, with the enthusiasm and joy of people returning after a long stay in another country. My son was sleeping soundly as I told him, with my eyes, not to ever crawl, not to ever walk, that it wasn’t necessary: I could carry him forever.

Translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell

Alejandro Zambra’s latest novel, Chilean Poet, will be out next month. He is the author of Multiple Choice; My Documents, a finalist for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award; and three previous novels: Ways of Going Home, The Private Lives of Trees, and Bonsai. He lives in Mexico City.

Megan McDowell is the recipient of a 2020 Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, among other awards, and has been short- or long-listed for the Booker International prize four times. She lives in Santiago, Chile.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/33SYtXj

Comments

Post a Comment