Billy Sullivan’s studio, a fifth-floor walk-up on the Bowery, has a comfortable, elegant dishevelment. Hanging all around the space are some of the brightly colored figurative paintings he has been making since the seventies: portraits of his friends, lovers, and other long-term muses, rendered in loose, dynamic brushstrokes and from close, pointedly subjective angles. A still life of a bouquet and two coffee cups is an outlier among the faces. Near a work in progress on the wall is a table with a color-coded array of pastels, each wrapped in its paper label (mostly the artisan Diane Townsend, with a few older sticks from the French brand Sennelier); a metal cart bears tubes of oil paint, and reels of film negatives are tucked away on low shelves. Tacked up on a set of folding screens is a display of Sullivan’s photographs and sketches, and next to that is a burgundy chaise longue adorned with a faux animal pelt. When I visited on an overcast afternoon in December, Sullivan had set out a bowl with grapes and a fig on the kitchen island, where he pulled an espresso for himself and poured a glass of water for me.

I had brought along a copy of Gary Indiana’s 2003 novel Do Everything in the Dark, a contemporary answer to George Eliot’s Middlemarch, which follows a tight-knit group of artistic New Yorkers who, over the years, have either realized or surrendered their potential for happiness. As Indiana explains in an Art of Fiction interview in the Winter 2021 issue of the Review, the novel began as a series of vignettes intended to accompany Sullivan’s paintings of people they both knew in the “downtown” scene. We looked through images together, and Sullivan told me some of the stories behind them. That milieu—Cookie Mueller was a part of it, as were Andy Warhol, Jackie Curtis, and the FUN Gallery founder Patti Astor—flourished for only a few years, from the late seventies through the tragic onset of the AIDS epidemic, and is often fetishized, much to Indiana’s irritation. The very word downtown carries a whiff of romance, especially when spoken by those too young to have known an era when you could live in Lower Manhattan on next to nothing. “There was a lot more free time,” as Sullivan puts it, and to be an artist essentially meant that “you got respect from your peers and you hung out with people you really liked.”

Sullivan is mild-mannered and considers himself a wallflower, an observer. While we sat and talked, he kept lifting his phone to take quick images of me as I fidgeted, recrossing my legs or tying up my hair. His photographs—he calls them his sketchbooks—have a loose, spontaneous quality, conveying an intimacy that invites the viewer in. The second time I referred to them as “candid,” he corrected me. For Sullivan, there is no distinction to be made between a candid photograph and any other kind.

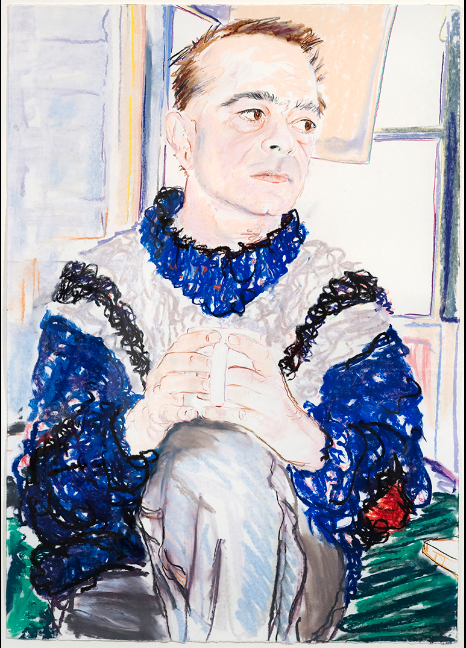

Gary, 1997, pastel on paper, 42 x 30″. All images copyright Billy Sullivan. Courtesy of the artist and Kaufmann Repetto, New York and Milan.

Gary was always around at night. I was interested in the way he wrote—dynamite art criticism. His writing was sort of like poetry. We ran pretty much in the same places at the same time. I’d see him when I went to the barber, and we’d go to the same restaurants, too, like Mickey Ruskin’s at One U. Places where you could go and get food and it didn’t cost anything. One U took the place of the back of Max’s Kansas City, where it first started for me. You would go to One U at around ten o’clock. Everyone would show up there, and you would play around. And then there was the Mudd Club. Gary would go. It was what you did at night. And it would be whoever was interesting. We never thought of it as the underground. It was just the world, and everyone was hanging out. You wouldn’t call somebody and say, “Are you going?” You would just show up.

You didn’t want to use the phone. There was all this paranoia because we were anti-war, we were anti all these things. And the older people, like Brice Marden and those guys, they would be really frightened of the FBI.

Gary became a muse for a while. We became friends over a long period of time, and it was always interesting—something was always going crazy in his life, and you got to hear that. We would have these long telephone conversations, kind of piecing together what happened the night before. In the morning you would check in and see when you left somewhere and what you did. It used to be a whole part of my life was, the next day, trying to figure out what exactly happened.

Cookie Mueller had a place on Bleecker Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues. And you’d go there, like before you’d go out at night, and get whatever you needed. Lots of times you went to Cookie’s to get drugs and get ready to go out. She’d be putting on her clothes.

Cookie called me a diarist. She used to work for some place called Details, and she wrote that in a review in there. And I liked it. It sounded like what it is. This is my diary.

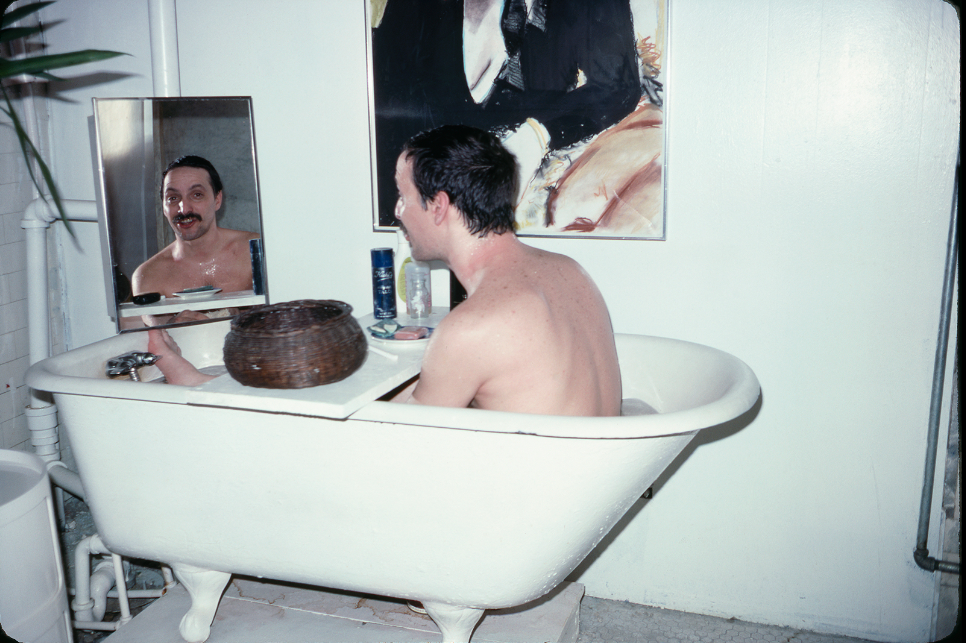

I get to go to lots of people’s bathrooms. That’s just, I’m friendly.

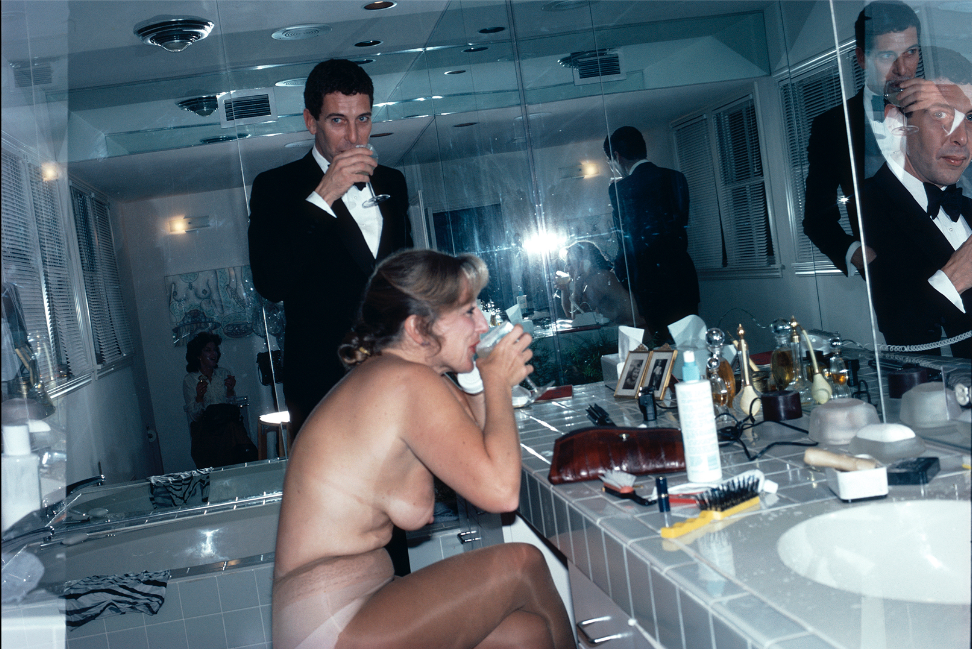

This is Anne, my husband Klaus Kertess’s best friend. She was a beard when we would travel sometimes. They were opening the Morgan Hotel, and she was doing a big party. And that’s the first bathroom at the Morgan. That’s her drinking her wine, talking on the phone, her favorite thing. Now she just texts.

Anne and Klaus, 1981 (printed 2002), digital c-print, 13.5 x 20.25″.

That’s Anne in the bathroom in Fort Worth. They were getting ready to go to a big party at the Bass Hall, and Klaus was doing an art show then, for Laura Carpenter. They’re having margaritas before we went out. When we got to parties in Fort Worth, Anne would give everybody an individual vial of cocaine so that we wouldn’t go into the bathrooms together, because she’d get in trouble.

Naomi Sims was the first really big Black Halston model. She was married to Michael Findlay, who is an art dealer. And she came to my house on Eighty-Seventh Street, all decked out in the Halston, just to have dinner, and to drink and have a good time. She was the most elegant woman ever.

I’m good at red. I got interested in them because they hung out with Jimmy Schuyler, and I always thought he was the most brilliant poet. I’d see him at Fairfield Porter’s house in Southampton, and he must have been on Thorazine or something. He’d just be sitting there like that, but still brilliant.

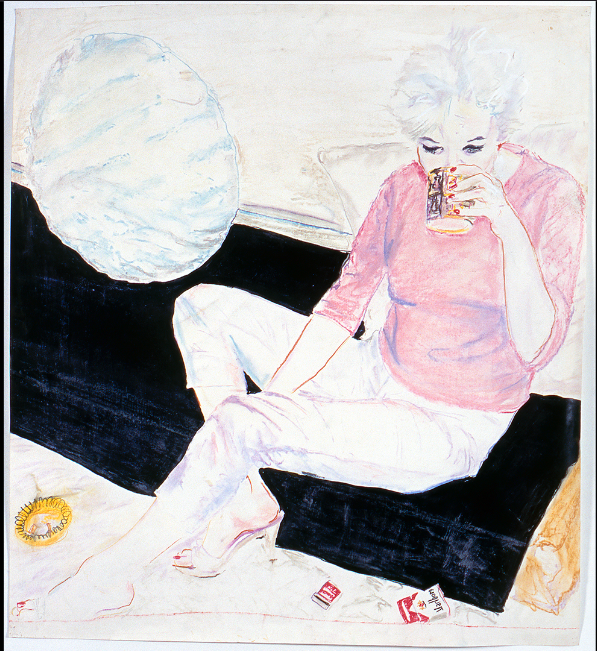

Patti Astor had a place in the East Village. One day we went over there, and you had to bring her a bottle of vodka. She had great makeup. She was something else. She was one of the beginnings of the East Village—she pulled all that together. This is in her home at like one o’clock in the afternoon. You know, the mattress on the floor with some pillows and Marlboros and ashtrays …

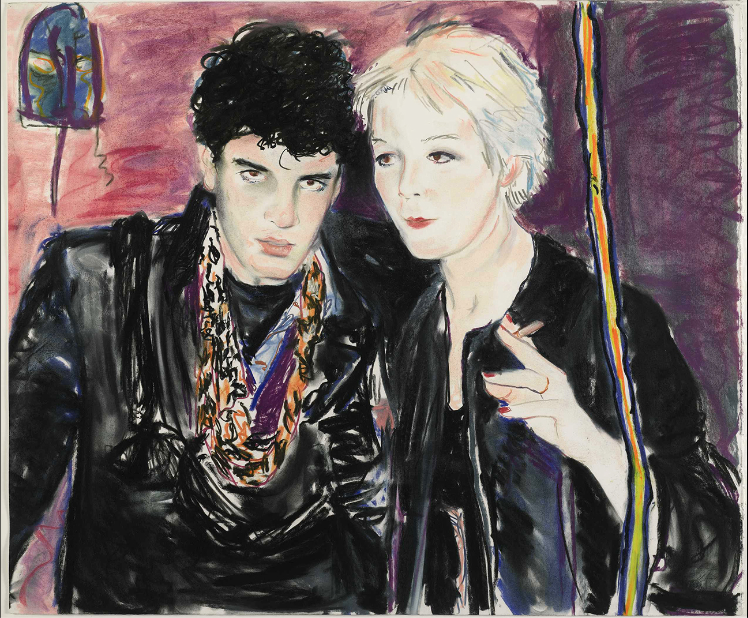

Louie and Patti, 1979, pastel on paper, 30.25 x 39″.

And that’s Louie Chaban. He was going out with Rene Ricard, then, that’s how I met him. Louie was once the doorman at the Mudd Club, and then when Soho started having fashion as well as art stores, he worked for Anna Sui. I’d go visit him when I was looking at art there, and we would take pictures, and we’d go out at night. I can be fascinated by somebody, totally involved in that person, and I can spend years doing it. Louie is somebody who I’ve done from when he had a twenty-six-inch waist until … He’s this big, huge, grumpy man now.

Gary and Cookie again. They were perfect together at night. They just had this whole conversation going. She seemed like she was always kind of whispering in someone’s ear. I’ve never seen Gary be really loud, and I don’t think Cookie had to be loud. She could get anything she wanted just being Cookie.

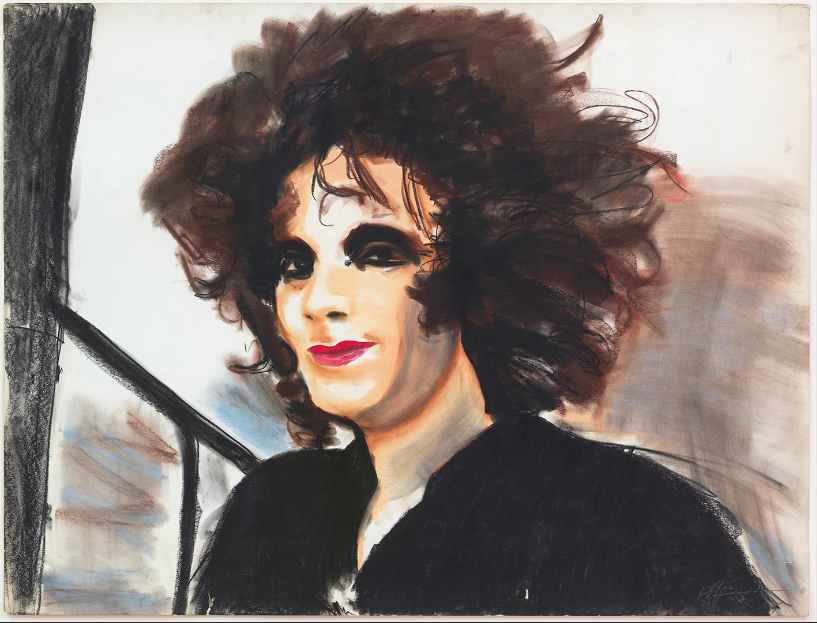

Jackie Curtis and I were in high school together. I didn’t know that until she told me later. My studio was on Eighty-Seventh Street, I had a spiral staircase. She came over and we started playing around. She was trying to get some money to make a movie. I worked on plays that she was in, too—I did sets for Andy Warhol. This is from around the same time as that great portrait by Alice Neel of her and Ritta Redd. Ritta Redd was there the same night, and Andrea Whips and Warhol were with us. It was a total Factory thing.

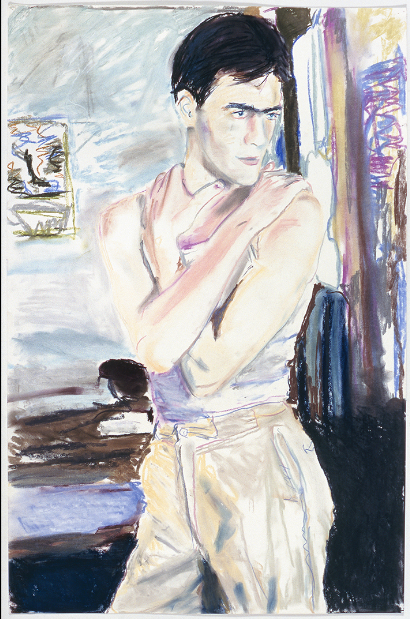

He was a boyfriend of Rene Ricard’s. He got undressed that day. It was really nice.

I never really paid attention to my photographs, because I just used them for reference. Some of them have become drawings and paintings. I could take a picture in 1979 or 1980, and I could make a painting in 2004 of that image—I can go right back and be there.

I never knew they were sketchbooks until somebody was doing a book about me. What they wanted were my photographs. And then I started noticing that they’re relevant, that they really mean something. They lock a time and a place, and puts me somewhere. They block time, so I don’t have to think about time. All I have to do is remember to organize my images. I tell kids now, “Don’t delete your images, because images that you delete today, one day will really look good.” Sometimes you can’t see what things look like until time passes. It’s like if you write for a living. You’ll write something one day. The next day, you’ll look at it. You don’t think it’s any good. And then a week later, it really makes sense, what you wrote. And that’s the same thing with images.

I used to love it when it was film in cameras, because you didn’t see anything. The film had to go away, and then it had to come back, and then you’d look at it. This time period that it took, it was kind of like sobering up—“Oh, this is what it was.”

Lauren Kane is an editor at The Paris Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/dJpO0Mc

Comments

Post a Comment