Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

In honor of the longtime friendship between BOMB and the Review, we’re offering a bundled subscription to both magazines until the end of February. Save 20% on a year of the best in art and literature—and for your weekly archive reading, a selection of authors that the two of us have each published over the years.

Interview

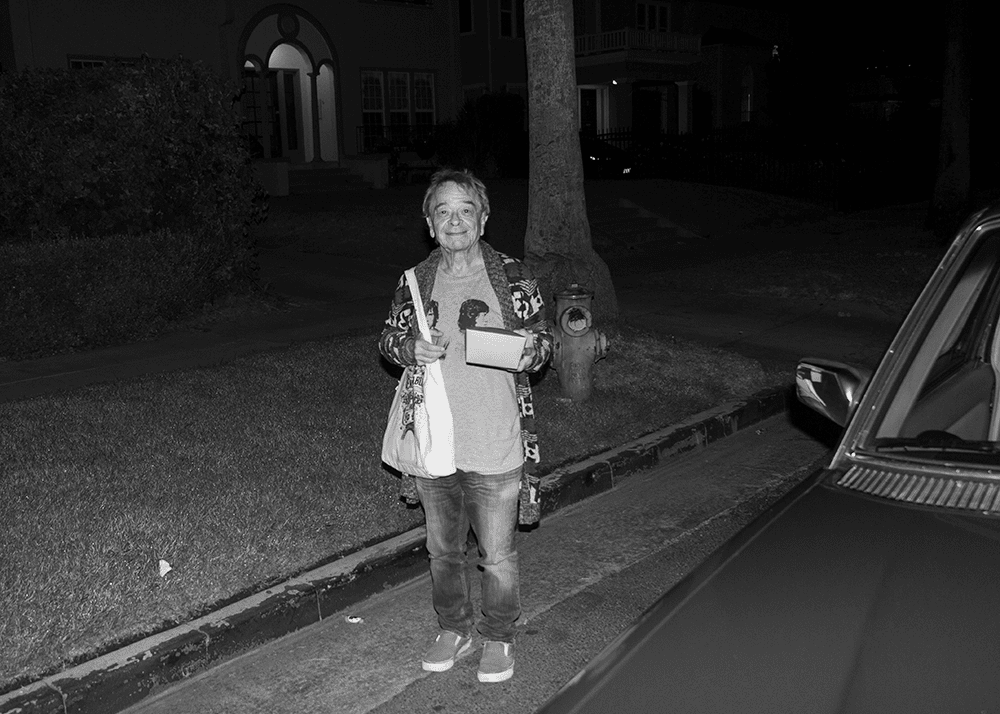

Gary Indiana, The Art of Fiction No. 250

Issue no. 238 (Winter 2021)

I was desperate to write a novel, but I didn’t have a story. Whenever I tried to write fiction it was all about my own inner bullshit. Writing about films and architecture and books was never the end point of what I wanted to do, but it forced me to get outside my own head, to describe physical objects and action. And then somebody handed me a story.

Fiction

Second Dog

By Kate Zambreno

Issue no. 228 (Spring 2019)

When I think about getting a second dog, I think about what we might name the dog. It’s exciting that we won’t have to disguise naming the dog after a writer or artist. Our dog is named Genet, and I fantasize about a little terrier named Violette Leduc, so if our Genet ignores her or humps her, I can pretend I’m enacting some literary gossip, as Violette Leduc always abjected herself to Genet in her desire for his friendship. With babies, there is more pressure to at least disguise one’s pretensions.

Poetry

Learning Persian

By Solmaz Sharif

Issue no. 230 (Fall 2019)

deek-teh

deek-tah-tor

behn-zeen

dee-seh-pleen

eh-pe-deh-mi

fahn-te-zi

mu-zik

bahnk

mah-de-mah-zel

sees-tem

vah-nil

vee-la

vee-roos

ahm-pee-ree-ah-lizm

doh-see-eh

oh-toh-ree-te

Art

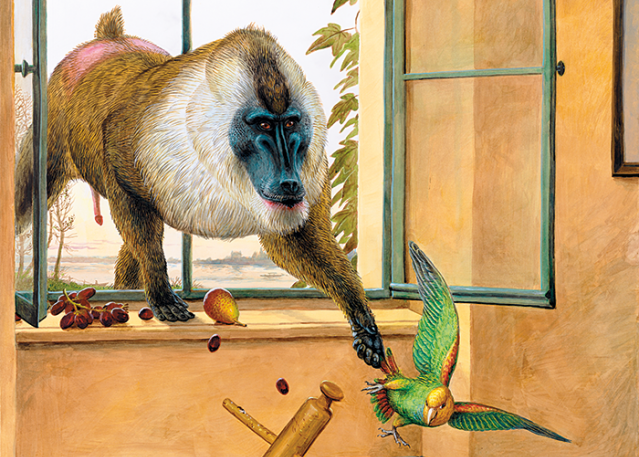

Walton Ford and Ryan McGinley

By Waris Ahluwalia

Issue no. 201 (Summer 2012)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/BK7jSdn

Comments

Post a Comment