A red planet in the foreground with a green planet in the distance, set in a starfield. Image courtesy of Adobe Stock.

In the wee hours of this morning, Ye shared a flurry of Instagram posts. There were videos advertising his proprietary Stem Player, which he claims will be the only place fans can listen to DONDA 2, the album he plans to release next week. “Go to stemplayer.com to be a part of the revolution,” he wrote. The Stem Player, which allows users to remix music by manipulating stems, or the individual, elemental parts of a song, is a disc covered with what looks like semitranslucent tan silicone, featuring blinking multicolored lights that correspond to the tempo and other aspects of a currently playing track. Its design is of a piece with Ye’s Yeezy aesthetic: earth tones complemented by bright hues, like a Star Wars scene set in Tatooine. His posts recall George Lucas’s series in their narrative messaging as well: Ye highlights the battle between an evil empire—in this case, the music and tech industries—and an intrepid revolutionary, himself. “After 10 albums after being under 10 contracts,” Ye explains, he is ready to control the means of distribution. “I turned down a hundred million dollar Apple deal. No one can pay me to be disrespected. We set our own price for our art. Tech companies made music practically free so if you don’t do merch sneakers and tours you don’t eat … I run this company 100% I don’t have to ask for permission … I feel like how I felt in the first episode of the documentary.”

“The documentary” is jeen-yuhs: a Kanye Trilogy, a nearly five-hour bildungsroman that premiered at Sundance in January and is distributed by Netflix. Directed by the filmmakers Coodie Simmons and Chike Ozah, who made Ye’s first music videos, jeen-yuhs is shot in what appears to be vibrantly colored 8 mm—something of Coodie & Chike’s trademark—and is narrated by Simmons, who quit his job as a comedian and public-access host in Chicago to follow his friend’s journey. It’s a culmination of over twenty years of documentation and hundreds of hours of footage. Consequently, the film plays like a very long, intimate home video.

In the trilogy’s first part, which premiered on February 16, it’s the early aughts: Ye is hustling in New York City and working on what will become his 2004 album, The College Dropout. This is the portrait of an artist as a twentysomething young producer, a successful beat maker struggling to be taken seriously as a rapper. He goes into Roc-A-Fella’s offices and plays his music for busy A&R and marketing professionals, who half listen in between phone calls. We see him playing his instrumentals for other rappers, driving around New York delivering tracks, taxiing through the city with CDs of beats, waiting for his career to take off. We see him waiting in the wings of another rapper’s concert anticipating his chance to get on the mic, and then buying a porn mag from a newsstand. We see the empty refrigerator in his Newark bachelor pad. We see him spending time with his mother, the late Dr. Donda West, in her Chicago apartment. Dr. West’s confidence in her son’s abilities is touching; while watching Ye and his mom rapping one of his early songs in her kitchen one late night, I had to wipe my eyes. In this film, we see Ye built bit by bit; we see his stems.

One of today’s predawn posts was an excerpt of a track called “Fuck Flowers”: a video of the Stem Player playing the song in the dark, its blinking nodes like a pulsing beacon cast from a lighthouse, beckoning insomniacs, those in other time zones, and workaholics to come and listen. The device’s undulating light show matches the rhythm of Ye’s recent Instagram activity, which has functioned as a rapidly changing post-and-delete diary of his thoughts. For the past few weeks, he’s been sharing dozens of posts, which vacillate between harassing his estranged wife, Kim Kardashian, and her boyfriend, Pete Davidson; promoting his new album; and expressing a desire to restore his marriage. Beginning with 2016’s The Life of Pablo, an album notorious for its ever-evolving tracklist and sequencing, Ye has been editing his art to fit his moods. At the same time as he started live-editing his art, he began live-tweeting his thoughts. In 2018, for example, he ecstatically expressed his ideas about Donald Trump’s “dragon energy,” and his emoji skin-color preferences. Ye’s impulse to share has only intensified. On Sunday, he wrote, and subsequently deleted,

HERE’S SOMETHING I HAVE TO DISPEL MEANING REMOVE THE SPELL THAT PEOPLE ARE UNDER WHY DOES A MEDIA OUTLET GET TO POST 20 TIMES A DAY BUT IF I POST THAT AMOUNT THERE’S SOMETHING WRONG ISN’T INSTAGRAM OUR OWN PERSONAL MEDIA PLATFORM? … I LOVE BEING IN CONTROL OF MY OWN NARRATIVE “I FEEL KIND OF FREEEEEE”

The contrast between Ye’s impetuous Instagram dispatches and the thoughtfully arranged, two-decades-in-the-making jeen-yuhs is a fruitful artistic juxtaposition: between a hastily assembled chronicle and a more reflective composition. We can see two chronologies in motion, two contradictory but complementary records in play, suggesting distinct, but overlapping destinies—hinting, like Tatooine’s binary sunset, at elliptical experiential timelines. Holding the two together means witnessing a pleasant anachronism, as sweet as Ye’s old sped-up soul samples. “We get a good juxtaposition now in this film between the two lenses,” says Chike Ozah, referring to balancing the media’s critical view of Ye with a more empathetic one, in an interview with Netflix. On the College Dropout classic “Two Words,” Ye plays with the power of contrasting pairs: it features Freeway, who was then a hard-core street rapper, and Mos Def (now known as Yasiin Bey), the Toni Morrison–quoting indie-rap darling. Throughout the song, the featured artists use the refrain “two words” before juxtaposing sets of images. Ye begins his verse by establishing the scope of his playground—“Southside, worldwide”—which is both local and cosmopolitan. In light of the duality offered by his social-media narrative and the documentary—a long view alongside a short one—I wonder what words he’d use to describe himself now. For me, two words come to mind: recording artist.

In one jeen-yuhs scene, filmed with Ye and Dr. West at his childhood home, the musician says, pointing at the space where a full-length mirror used to be, “I used to just practice in front of it.” It’s not hard to imagine; in several scenes, Ye flexes for the camera, posing and preening. Oh, how things have changed. For Ye, these days, mugging in front of the camera is like mugging in front of a mirror. At the beginning of the film, a Roc-A-Fella A&R rep asks him, “You still doing your documentary? I thought it’d be finished.” Ye replies, “It’ll never be finished.” —Niela Orr

I knew that Joachim Trier counted Arnaud Desplechin’s 1996 film My Sex Life … or How I Got into an Argument as an influence—he said as much at a recent talk at Lincoln Center—but was delighted by just how deeply Trier’s new movie, The Worst Person in the World, reminded me of the former when I finally saw it last week. The Worst Person in the World, like My Sex Life, is a freewheeling exploration of one’s early thirties—that delicate age at which actions do indeed begin to have consequences but it’s still fun to occasionally blow up one’s life in a moment of boredom. From the voiceover to the adultery plot points to the menstrual-blood shower scene, Trier borrows freely from Desplechin, though he swaps the gender of his main character, Julie. The result is a witty, realistic look at the highs and lows of finally growing up, and might include the best sex scene I’ve ever seen—it’s certainly the best sex scene in which the characters don’t even touch each other. —Rhian Sasseen

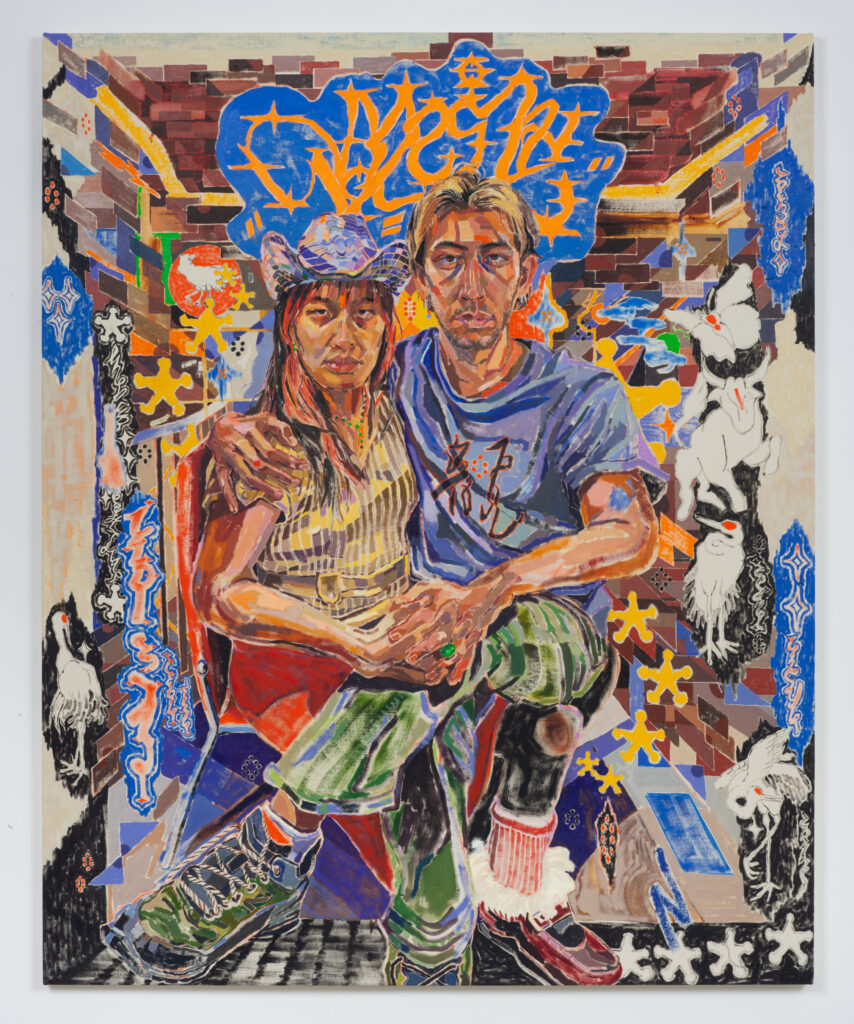

I first encountered the work of Oscar yi Hou—now an upcoming solo exhibitionist at the Brooklyn Museum after winning their third annual UOVO Prize—when I saw his A sky-licker relation at James Fuentes Gallery late last summer. The exhibition is a series of portraits, mainly of young Asian people. The subjects, through their various positions of vulnerability, stoicism, solitary ponderance, and mutual affection, stare directly out of intricate, kaleidoscopic frames to meet the eyes of their audience, positioning the viewer such that they take up the gaze that was once held and reciprocated by the artist. This dynamic between creation, creator, and beholder is simultaneously mediated and immediate, spontaneous and reenacted—an experience that is communal but also intensely concerned with the individuality of personhood. Seeing yi Hou’s work amidst a crowd of other twentysomethings fresh into the gallery from a day that had been hot and damp, hopelessly sweating through an outfit I had probably chosen with great effort for the occasion, I was faced with exactly that: the discomfort, the relief, the multiplicity and solitude of the person.

With me at the exhibition were several people who had modeled for the paintings. I saw them as they existed both in the real world and within the complex iconography in which the artist had immersed them: the dragon, horse, and ox of the lunar calendar; ornate lettering reminiscent at once of ancient calligraphic practices and contemporary American street graffiti; golden stars denoting the Chinese flag as much as the classic westerns of old Hollywood. Graceful and precise, these aesthetic references index their subjects as global intersections of past and present, living fulcrums upon which a multitude of dreams and inheritances—fame, beauty, nationhood, belonging—have come through time to balance. Standing before their portraits, sharing with them my reality and the collisions of perspective inherent to it, I felt that transhistorical identity reflected within myself. —Owen Park

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/ay5BQG1

Comments

Post a Comment