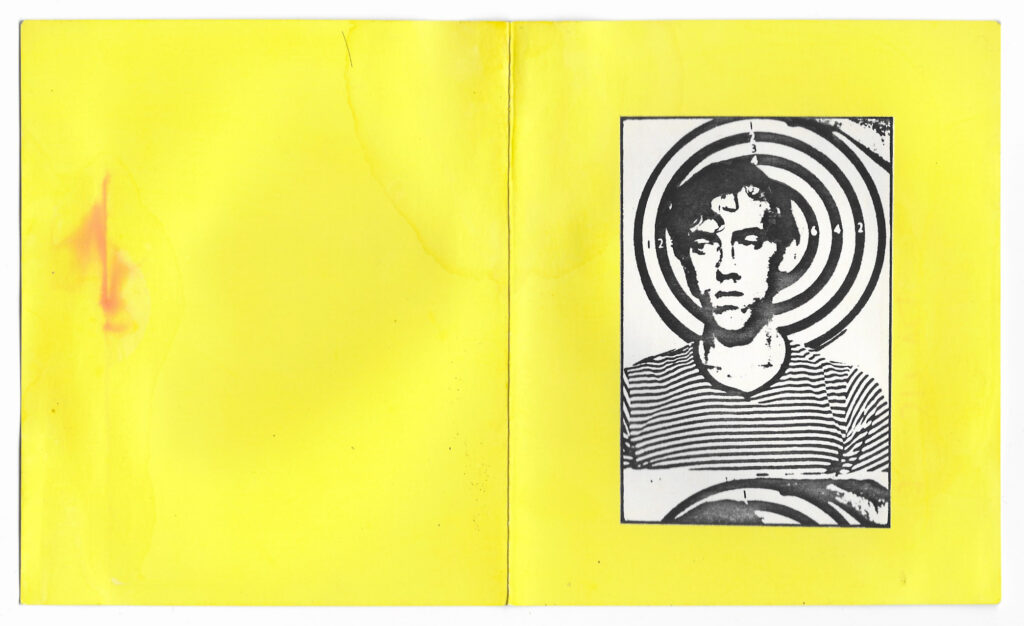

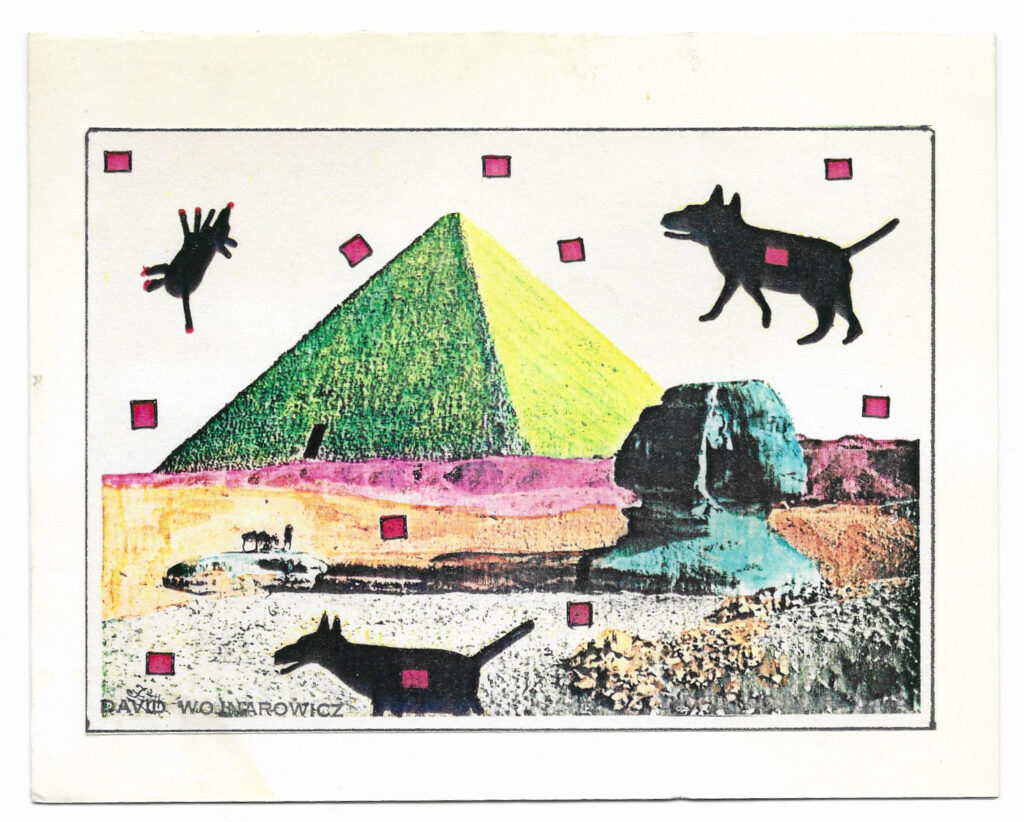

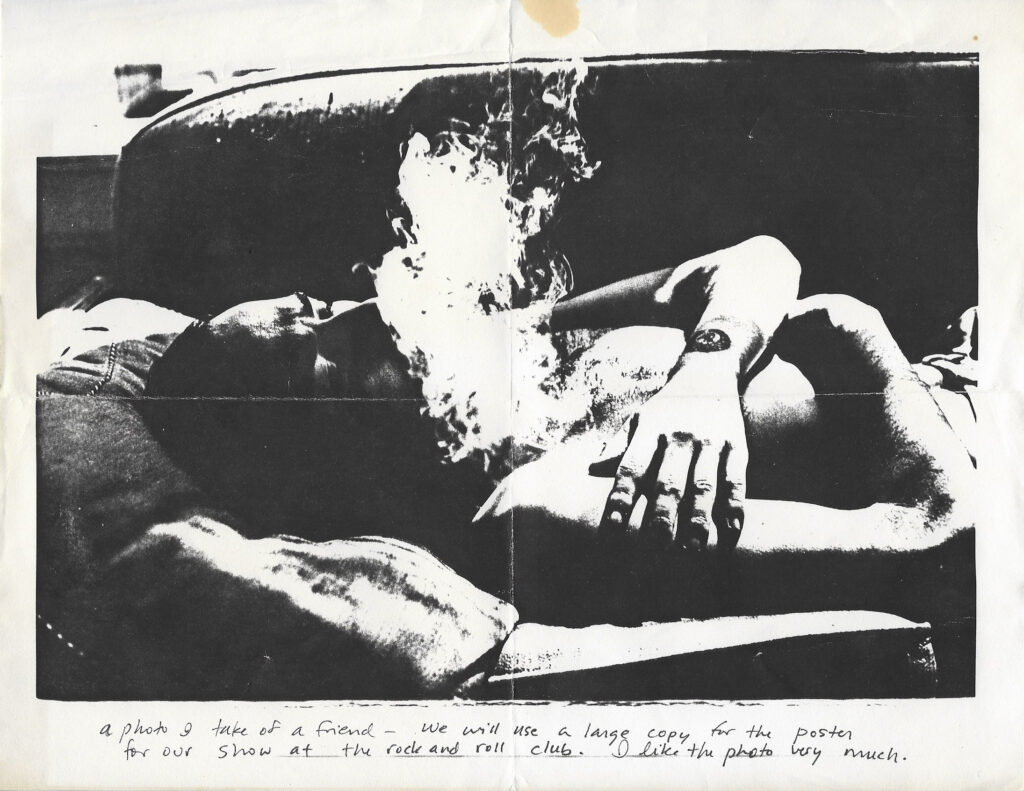

David Wojnarowicz, Oct. 22nd postcard, from the Jean Pierre Delage Archive of Letters, Postcards and Ephemera, 1979–1991. Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York.

David Wojnarowicz’s final home was on the corner of Second Avenue and Twelfth Street on the Lower East Side. He moved in after the prior tenant, his mentor and former lover Peter Hujar, died of AIDS. A few months later, in 1988, David was diagnosed with AIDS himself; he’d die in the Second Avenue apartment four years later at the age of thirty-seven.

Every time I visit the corner across from his apartment, I picture David walking out the door on a cold morning. The puff of his breath, the posture I imagine being poor. The cartoon cow he once spray-painted in the intersection for Peter to see from the window. David’s tall frame in the same arched window, looking for men. “Sometimes I almost fall out the window,” he says in a 1988 tape diary, “trying to watch them walk down the street.” They’re so hot and so sexy, he says, that it makes him laugh. I stand outside what is now a bagel shop and stare at the window where David laughed.

Last year, I didn’t visit the apartment for six months, because a doctor who worked in the area broke up with me, and I couldn’t bear the idea of running into him, not in the indignity of summer humidity. When I finally walked up Second Avenue again, I stared at every pedestrian, paranoid, looking for a gait I recognized. Somehow David felt about as likely as the doctor to appear. Neither would look exactly as I expected, my memory having shifted their features. The fact that they had each been on this street at some point meant that they’d continue to be there always. I have this sensation in New York sometimes—that time is sedimentary, layering instead of progressing, that it’s all happening at once.

Untitled (“Friendly Cow” for Peter Hujar), 1982. Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York.

David grew up in New Jersey and New York, spending some of his adolescence homeless, turning tricks in Times Square. In his twenties, he often crashed with friends or family between apartments, and worked as a busboy. Creatively, David, who became known as a part of a scene of Lower East Side artists that emerged in the eighties, made all kinds of work: photographs, paintings, films, music, essays. In contemporary remembrances, he and his work are nearly always described as angry. Much is made of this rage, as if it were his primary characteristic. David, by his early thirties, was dying unnecessarily, as were many people in his community, and his work radiates a rational fury, a desire to live, a murderous daydream of justice; this was often aimed at politicians who unabashedly called AIDS a punishment for queerness. In Close to the Knives, the memoir published the year before his death, David writes, “I carry this rage in some moments like some kind of panic and yes I am horrified that I feel this desire for murder.” But the feeling is paired with memories of “the faces and bodies of people I loved struggling for life, people I loved and people who I thought made a real difference in the world.” He was constantly saving sick animals. He believed in the value of beauty, even in plague times. His writing and tape diaries are tender, lustful, elegiac, self-critical.

I love David’s mischievousness, like the time he released a herd of “cock-a-bunnies,” cockroaches with little ears and cottontails glued to them, into a group show at PS1 he hadn’t been selected for, then added the exhibition to his resume. I’m moved by his tenderness, his tone in a journal entry from late 1978 when he describes sleeping with a new lover, Jean Pierre Delage, soon after moving in with his sister in Paris. In the morning, Jean Pierre made breakfast, heating coffee on a camping stove and taking butter and a half loaf of bread from the windowsill. This meal “tasted like food from the banquets of Monarchs,” he wrote, “but EVEN BETTER!”

David’s early photographs are on display in a new gallery show, Dear Jean Pierre: The David Wojnarowicz Correspondence with Jean Pierre Delage, 1979–1982. Included are some from his Arthur Rimbaud in New York series, of Jean Pierre and others wearing a paper mask of the French poet’s face while standing in the cruising grounds of the Hudson River piers, masturbating, shooting up. David felt a deep identification with Rimbaud: their lives paralleled in experiences of parental abandonment, their shared queerness and devotion to their art, and their birth years, which were exactly one hundred years apart. In the photo series, shot in the late seventies, David merges their lives, bringing Rimbaud’s face into the haunts of his own youth. These portraits of fandom are some of David’s best known images.

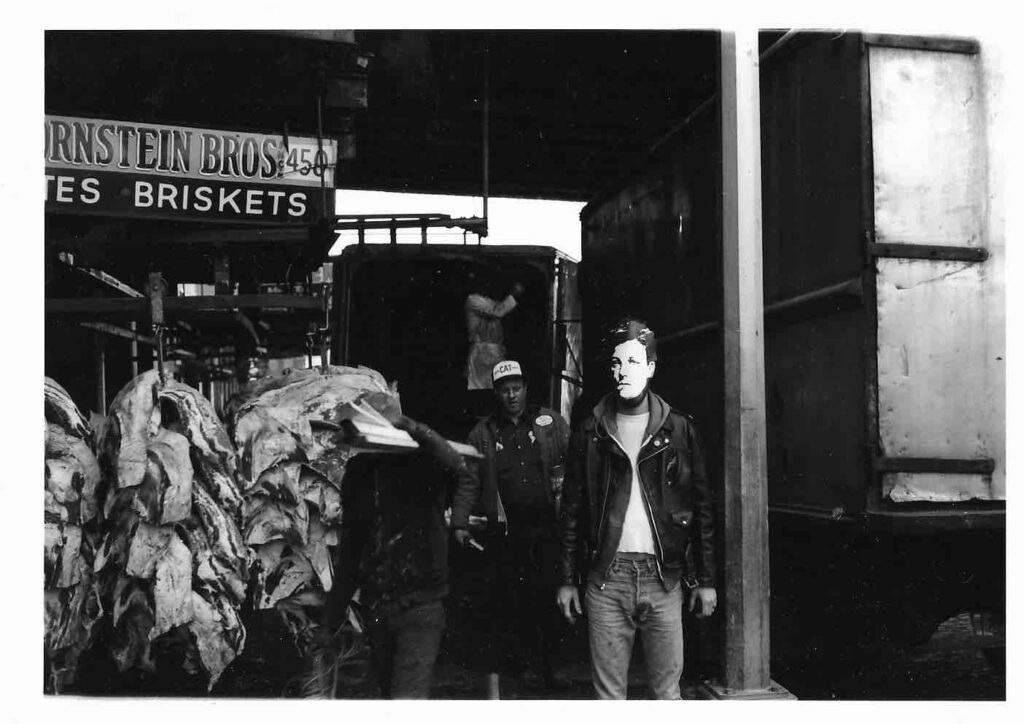

Arthur Rimbaud in New York (J-P Briskets), 1978–1979. Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York.

But the show centers on David’s letters to Jean Pierre following his 1979 return to New York, after that first stint in Paris. Hundreds of postcards, typewritten sheets, and handwritten notes on the back sides of artwork in glass displays line each wall of the two large rooms. The letters are journal-like in their thoroughness; they chronicle David’s recurring searches for jobs and stable housing, the temporary acquisition of each. David is confused about his future but not about Jean Pierre, he insists, wondering if they should live together in Paris or New York, and when. “I close my eyes and can see you,” David responds to a letter Jean Pierre wrote on the Métro, “I hear the sounds of the train in the station, the lights, the sounds of the doors opening. Hmm …” The letters animate the young David who, decades after his death, I so longed to befriend. He is loving and forthright, attentive to the world around him. “Ça va,” he opens many of the letters, peppering them with his limited French, like the names of the months—maybe by juillet he’ll have the money to visit Jean Pierre. In an early letter, David signs off: “I am in a cafe in Brooklyn right now. Frank Sinatra on the jukebox—a waitress who looks from outer space. Church bells ringing. Take care, love, David.”

“We wrote to each other every day, or almost every day,” says Jean Pierre in French, in a videotaped interview playing in a small room off the main galleries. The letters could take up to three weeks to arrive. Some days, he’d receive more than one, and he’d always respond immediately. This ardent correspondence lasted three years, after which point Jean Pierre and David stayed in touch, but stopped planning for a future together. Jean Pierre saved the letters, he says in the interview, because right until the end—and now he tears up—he thought they might get back together.

When I returned to the main gallery on the night of the opening, I recognized Jean Pierre from the orange-brown tortoiseshell frames of his glasses among the minglers. I walked over and planted myself next to him, pretending to read a letter in the same glass case. He was wearing a gray herringbone crewneck over a mustard shirt, blue jeans. His hair had gone gray. Jean Pierre was pointing to the last letter, an epilogue of sorts, written in 1991, nearly a decade after the rest. He explained to a man standing next to him that the reference to apartment shopping was nonsensical, years after Jean Pierre had sought an apartment; by this point, David’s mind was going. I lingered for a long time, watching Jean Pierre wave his hands, holding one end of his glasses in his mouth. I didn’t speak to him: I was, in a sense, as proximate to David as I might ever hope to be, with someone who could answer my questions. But to speak to Jean Pierre would have been to turn on a light in the darkroom of my fandom. The exposure of his attention, his opinion, risked ruining something sacred to me, something very intimate that can be sustained only by apartness. That’s what I want out of fandom, if you can call it that—to love without accountability or surveillance. So I just stood there, transcribing his words and gestures in my notebook, until I feared it was becoming obvious, and then I walked out onto the street.

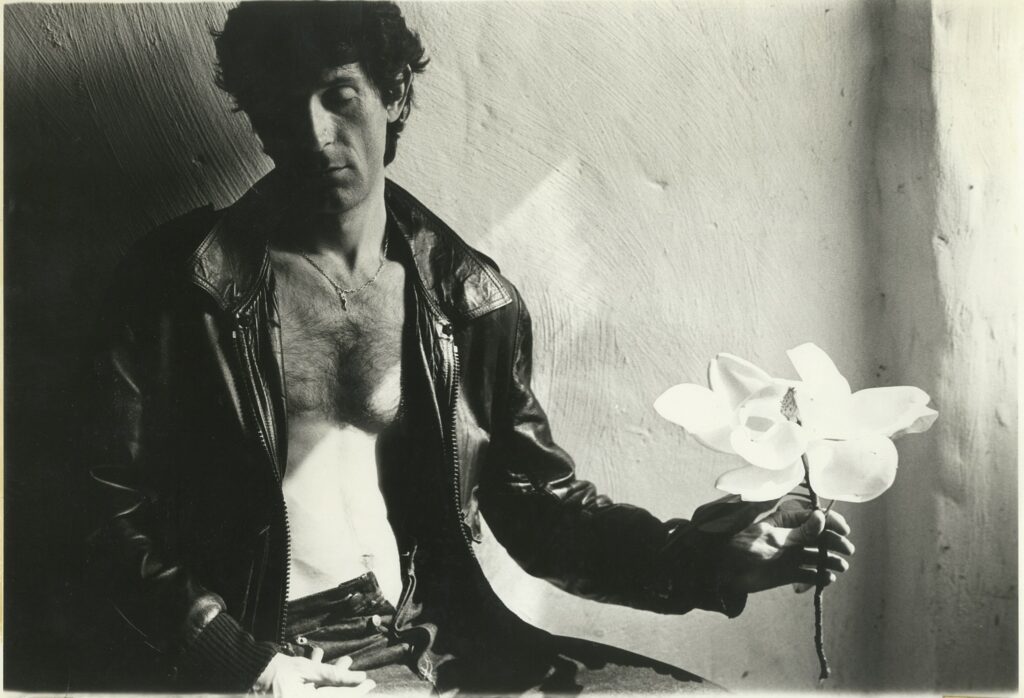

Jean Pierre D. Normandie, France (Male series), 1980. Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York.

I’d seen David’s letters before. I used to go to his archives in the Fales Library at NYU one afternoon a week before the pandemic, moving through the materials slowly, just an hour or so per trip. Voicemail tapes, mail, journals, his wallet, his glasses. I never made it to the glasses, actually. I was too afraid to reserve them. I asked a mentor of mine who also cared about David what you do once you have them, joking offhandedly about putting them on, which horrified her. To be honest, it would have embarrassed me to sit looking at them in public, in front of the docents and other researchers at the archives. A couple of weeks ago I was reading Garth Greenwell’s novel Cleanness on the train; I had to stop when a man sat next to me, afraid he’d glimpse the sadomasochistic sex scene. I’m sure the man wasn’t looking over my shoulder, but it was too private a moment to share. It would be the same thing, to see the glasses in public.

One night when we were dating, I took the doctor to the corner across from David’s. We’d just eaten at the Jewish deli, bowing towards the space heater they’d installed outside. I’d gone on too long about the genius of a book by Sheila Heti he hadn’t liked. I was always eager to talk about the scene of cock worship directed at a man named Israel, the heavy-handedness of its commentary on worship, the relatable farce. How religiosity can leak elsewhere for those of us prone to it. I defended the novel out of loyalty to the author. The doctor promised to try reading it again. Then I walked with him to David’s corner. We stood staring, and the doctor asked me how I knew when to leave. I said it’s just a feeling, like a long pause, and that’s it.

“I try talking to him wondering if he knows I’m there, if he sees me,” David writes after Peter’s death. “I know he sees me, he’s in the wind, in the air around me. He covers the field in a fine mist. He’s in his home in the city.” I don’t think David could see the two of us, the doctor and me, looking at the windows of that same home in our city. But I felt that sensation of time overlapping, that we were all there at once, me with both men, onto whom I’d affixed many projections, many hopes of kindredness.

Dec. 26th postcard, from the Jean Pierre Delage Archive of Letters, Postcards and Ephemera, 1979–1991. Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York.

I used to do this same exercise when I lived in Berlin, bringing out-of-town guests to Franz Kafka’s old building—“This was his view every morning!”—but I realized after a year that I had the wrong address. I’d brought people to a random building and animated a false history, as if that’s another layer too, the things we imagine to be true, living on top of or below reality.There was a moment in the archives when a similar fiction ripped. I was reading his mail, sifting through postcards from Nan Goldin, bills, faxes from his agent. There was also a letter from a fan. A horny, obsessive letter. The writer dreamt of David three nights in a row. They’d met once and there had been some electric current between them, the man wrote; he was sure they’d fall in love, even at a distance. And in the same cream folder of correspondence there was a draft of David’s response, a generous and measured typewritten note. He understood the velocity of fantasy, the way it can hook us by the belt loop and tug us along. From a distance, he wrote, “You can fill a person up with all associations and projections and myths and desires.” Kindly, he reminded the man of his own human form, the reality of the embodied, actual David. “I don’t know what I represent to you,” says David. “You don’t really know me at all.”

With the letter in my hands, I looked around the room, caught, my cheeks flushing at the reprimand I was taking personally. Embarrassing, the publicness of the moment, like reading Cleanness on the train. So David reached through the decades and caught me by the wrist, calling the bluff of our intimacy. I sat stunned, because there is no remedy for this feeling that no, it would have been different with me—just more projection.

Postcard from the Jean Pierre Delage Archive of Letters, Postcards and Ephemera, 1979–1991. Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P·P·O·W, New York.

When someone dies, the traditional Jewish condolence is: May their memory be a blessing. This is a sentiment for the living, not the dead. I wonder what warping comes with fandom, when the relationship is mediated by inaccessibility or death; the attachment is some combination of honoring and consuming a legacy. I think of David, dressing his friends in the paper mask of Rimbaud, claiming a lineage in the poet, or the figure he imagined of the poet. I place myself, less because of identification, and more out of simple affection, in David’s wake.

After all those months away, it felt good to stand on David’s corner again. This time, it was the right apartment, I was sure. There’s a movie theater on the ground floor; it used to be a Yiddish one. I walked by the building and held out two fingers, dragging them along the stone wall till they buzzed from the vibration. And when I turned the corner onto an empty street I held my fingertips to my lips, the way I do after I touch the mezuzah on the doorframe of my apartment, but only when I am alone. I remember so clearly driving home once in high school after a first kiss, through a green light on Vista Street, up the hill, with my left hand on the wheel of my father’s Prius, the fingers of my right hand to my lips, the kiss fizzing and crackling there. And it felt like that, walking down Eleventh Street, the same fingers pressed covertly to my mouth. The same strike of connection.

When I walked back towards the train, I felt a kind of attentiveness. A great mood. I think because of the intimacy, which fascinates me because it’s totally false, and also because I felt a rush of relief to not have seen the doctor, whose gait, it occurs to me now, I can no longer picture.

Hannah Gold is a writer based in Brooklyn. She coedits Berlin Quarterly and teaches writing at Columbia University.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/iT28rqf

Comments

Post a Comment