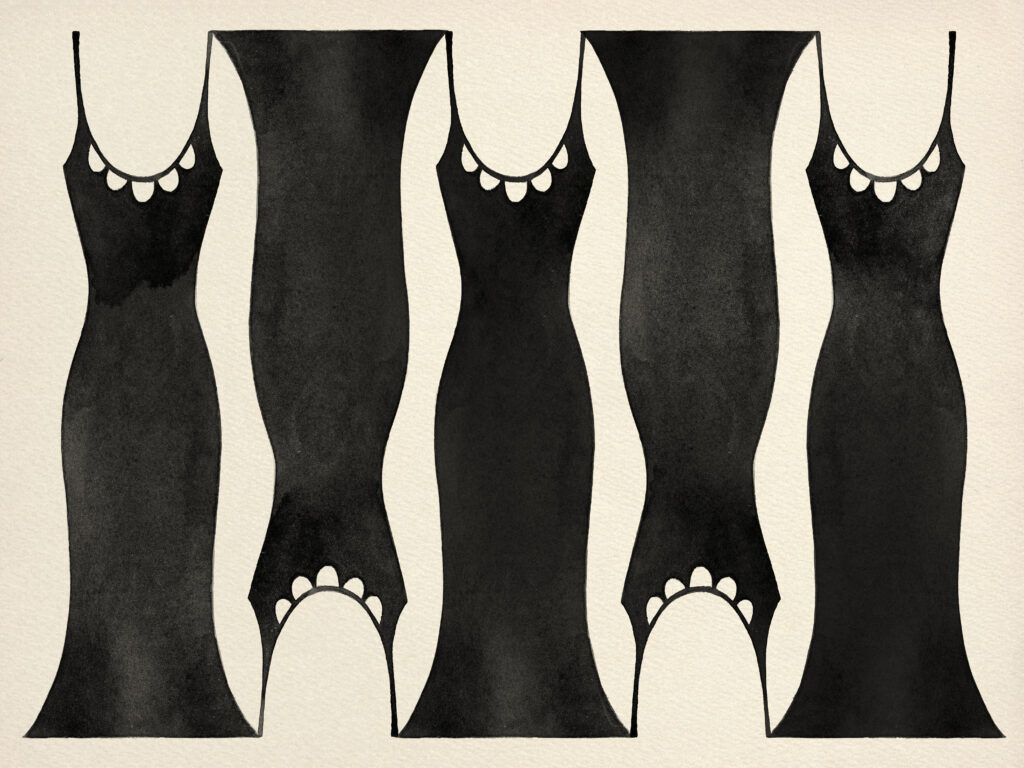

I bought the dress known in inner circles—that is, in the echo chamber of my closet—as the Dress in 1987, for a rehearsal dinner in New York for a couple I’ll call Peter and Sally. I found it on sale at Barney’s on Seventeenth Street. On the hanger, it looked like a long, black cigarette holder. It was February, and outside on the street, the wind was coming up Seventh Avenue. I had been married for exactly one month. That year, all my college friends were getting married. We barged from one wedding to another, carrying shoes that hurt our feet. In some cases, we knew each other all too well; sometimes the marriage was the direct result of another marriage, on the rebound: someone’s beloved had married someone else, chips were cashed. In this instance, I had hung around with the groom on and off through college, and the bride had once been the girlfriend of the man I left when I met my husband. The Dress was a sleeveless crepe de chine sheath, with a vaguely Grecian scooped neckline composed of interlocking openwork squares, which sounds dreadful but was not. It was sublime. Cut on the bias, it skimmed the body—and, it turns out, it skims everyone’s body: the Dress has been worn to the Oscars three times—in 2001, 2009, and in 2018—though not by me.

In 1987, the nominees for Best Picture were Platoon, Children of a Lesser God, The Mission, Hannah and Her Sisters, and A Room with a View. That year, my husband and I had spent our winter honeymoon in Italy, at the pensione in which Lucy Honeychurch feels so fettered in A Room with a View; we’d eaten our tiny breakfasts from pink plates. Hannah and Her Sisters was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won three, including Best Original Screenplay. In those days, I lived in a tiny apartment on West End Avenue with a window that looked out onto the brick wall opposite. In the spring, the wall was covered with morning glories. During those years, my friends and I were eating ramen dry out of the packet and still scrounging, late at night, through the refrigerators of our parents’ apartments—which looked like the apartment in Hannah and Her Sisters—on Central Park West and Riverside Drive, at after-parties that went on long after they should have ended. The movie seemed to us about people inconceivably older than we were, making bad decisions of the kind we would never make. When we thought about our futures it was as if we were looking through the wrong end of a telescope. The week I bought the Dress, a friend of mine saw a man jump from an upstairs window and hurtle into the courtyard of her parents’ Riverside Drive apartment below. She was sitting next to her parents, and her brother, with a girl from Ohio whom he planned to marry. No one said a word.

Of the evening of Peter and Sally’s rehearsal dinner I remember little, except that the heel of my shoe detached when I stepped out of the subway on Seventy-Seventh Street, and that the Dress made me feel like Anjelica Huston in Prizzi’s Honor, a film that had been nominated for Best Picture the year before. Or, at least, that was the idea. ( “Do I marry her? Do I ice her?” asks Jack Nicholson, as Charley Partanna, in the film’s best lines. “Marry her, Charley,” says Huston, as Maerose Prizzi. “Just because she’s a thief and a hitter doesn’t mean she’s not a good woman in all the other departments.”) For the wedding the next day I wore a sleeveless blue-plaid silk dress of my mother’s, made by Jacques Fath in 1952, which was tight in the waist. I was too hot and the zipper broke. The next year my husband and I had a child, and that spring we took her to Florence, where she fell in love with the pigeons in the piazza by Santa Maria del Fiore, and we discovered that at least four pensiones near the Uffizi claimed to be the one where A Room with a View had been filmed.

But the Dress? Like many things we think belong to us, it’s had a life of its own, like an old lover who resurfaces, now a fish wearing a waistcoat, in dreams. In 2001, extracted from behind a pile of snowsuits and maternity clothes, it went to the Oscars, for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, written by Kuo Jung Hsai, Hui-Ling Wang, and James Schamus, which had been nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay. “What am I going to wear?” Schamus’s wife, Nancy, had asked me as we sat in the Riverside Park playground six months before 9/11, watching two little girls pour cold sand on each other’s head. A decade later, in the second year of the Obama administration, the Dress walked the red carpet, worn by my friend Margaret, when her husband, the cinematographer Tom Hurwitz, was nominated in the Best Documentary (Short Subject) category, for Killing in the Name, a film about Islamist terrorism. In 2018, my friend Susan, whose husband, André Aciman, wrote the book Call Me by Your Name, came over one afternoon a few weeks before the Oscars to show me and my youngest daughter her outfit: a silk skirt printed with roses, and a shirred black V-neck top. Susan and I pulled a black beaded jacket I had bought at Housing Works out from my closet, and substituted a black silk shell for her top. She wore her own shoes and looked ravishing. From where she was sprawled on my bed, my daughter called, “You should feel like you, not like you’re wearing someone else’s clothes!” Susan looked grim. “I am wearing someone else’s clothes!” she replied. She gave the beaded jacket a gimlet eye. “I think it’s too much.”

“Show her the Dress,” my daughter called back. By now, Susan, who has raised three boys but no girls, was back in her jeans and sweater, ready to go. “I have to get undressed again?” she said, rolling her eyes. The Dress was in a garment bag in the back of the closet, stowed away with a navy-blue evening gown that had been worn only once. “Really?” said Susan. In a moment, the Dress was slipped over her head. “I like it,” she said. “Whose is it?” “Yours,” my daughter said.

When I bought the Dress, I was taking the first steps into the life that would turn out to be my own. By the time it went to the Academy Awards the first time, I’d had a child, gotten divorced, married again, acquired stepchildren, and had another child. In my closet now is a row of dresses I can’t bear to give away: three prom dresses, worn by my three girls; my second wedding dress, a floor-length Edwardian gown made of burgundy velvet, with a jeweled bodice; a fern-green dress embroidered with holly berries, which all of my daughters loathed and called the Christmas Dress; my first Alaïa, impossible to walk in; an apricot dress with a row of twenty-five covered buttons, by Jean Muir, that I wore to my own first rehearsal dinner. The Dress hangs among them.

Last summer, when I told my mother about the Dress, she paused for a minute. Then she said that she, too, had had a dress that went to the Oscars—in the sixties! “Who wore it?” I asked, incredulous. It was hot, and we were eating egg-salad sandwiches. I hadn’t seen my parents in a year. She couldn’t remember. “It was the wife of someone named Marvin, who was in the business,” she said. She turned to my father, who was alive then. “Was her name Carol?” “No, it couldn’t have been Carol,” he said. “She was too zaftig!” What kind of a dress was it? I asked. My mother smiled. “A little black dress.”

“I have loved you for the last time. Is it a video?” sings Sufjan Stevens in “Visions of Gideon,” at the end of the film version of Call Me by Your Name. Is there ever a last time? Always, it’s hard to tell. “The heart is a very, very resilient little muscle,” says Mickey in Hannah and Her Sisters. The last time I wore the Dress was in May four years ago, at a preprom party at the Knickerbocker Club. Parents were invited to see their daughters off to their first soiree—the beginning of another movie: the one in which they go off into their own lives, and we take the long view. We stood looking out on Fifth Avenue, clutching our glasses of wine, sweating a little, so close together in the festive shimmer that another mother spilled a little wine on the Dress when I jostled her with my elbow. Parties used to be like that; perhaps one day they will be like that again. “You must forgive me if I say stupid things. My mind has gone to pieces,” says Cecil Vyse in A Room with A View. From the top of the spiral stairs I could see my daughter in an emerald-green silk charmeuse slip dress, linking arms with her two best school friends. Her date was a boy she’d known since childhood, the son of one of my old friends from college. (I’d asked her if she wanted to wear the Dress. “No!” she said. “I’m saving it for the Oscars!”)

In my household the first question about any party or outing is, What did you wear? After the first lockdown, I left the city for some time, and when I came back, I saw three dresses, the ghosts of yesteryear, hanging on the shower rod in the bathroom—dresses I had worn the week before the background music of New York switched over to the sound of ambulance sirens. Afterward, what did we wear? Leggings and sweaters and T-shirts and sometimes, for days, the clothes we wore to bed. Now, holding our breath a little, we’re going out again, but tentatively. This year, no one has asked to borrow the dress to go to the Oscars. I plan to wear it myself in front of the television. I’ll pair it with my COVID cardigan, a brown, tweedy wool affair I wore almost every day for two years, unless my daughter manages before that to light it on fire—for, as she says of so many things, she never wants to see it again.

For some of us, what we wore connects us to our former selves, but now the world has changed again in terrible ways. In an interview with Sabrina Tavernise of the New York Times last week, Vika Kurilenko, a television screenwriter and journalist who escaped Bucha, northwest of Kyiv, with her three children, and whose husband threw himself across their youngest daughter to protect her from flying glass, said, “I left my diaries, my children’s toys, my dresses.”

Cynthia Zarin’s most recent book is Two Cities, a collection of essays on Venice and Rome; a novel, Inverno, and Next Day: New and Selected Poems are forthcoming. A longtime contributor to The New Yorker, Zarin teaches at Yale.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/0o3UlPY

Comments

Post a Comment